When the earthquake came, all the little white houses in the row shook like brides at a mass wedding; their insides shook, the chandelier hearts and inner cooling systems, the glass windowpanes shook like eyelids about to roll out a tear. My neighbour ran out in his underpants, clutching his children and a bulging bag with him. He saw me standing under the trees and told me there was so little time, I should go back in to fetch whatever I valued in the house.

It wasn’t at once clear to me what I was supposed to feel because this was such an intimate encounter with the earth breathing under one’s feet, alive, heaving a sigh and wishing to turn over to refresh itself -- no more. Somehow it was hard to conjure up terror of the moment.

I couldn’t really focus but in a flash I turned over the contents of my little house full of toys that I loved dearly; books of poems, paintings, terra cotta animals, embroidered bookmarks, knitted socks, cowries collected from many seashores. What could be salvaged from there? The fresh laundry perhaps or an elaborately prepared meal with the ingredients bought in various farmers’ markets -- sea salt, first-press olive oil, slow ground spices, quinoa, brown eggs, broccoli and raw honey?

The man I loved was not with me, so I blessed him wherever he was, and kept on sighing and standing under the trees.

What did I need from the house? It was important to stay with the turbulence of the passing moment and to look at everything. All the things in the house were to be looked at anyway. Even food was what I ate with my eyes. Why did I fear things leaving me?

Did things ever die or were they broken to be transformed, like me?

I knew that furniture bits could be angry, especially when I returned from my travels and opened the door to the house to catch them in their moods. I had experienced the sullen console table, the petulant wing chair, the bric-a-brac polished with dust like a conspiracy.

I often felt the clothes in the wardrobe had plans of their own -- definite plans on how to live their lives -- which I did not quite live up to and I had plenty of resentful shoes that sometimes refused to fit, sometimes relented.

Things had lives of their own fashioned by the artisans who created them, people who put them on the market, and people like me who married them and brought them home to live with forever. But they had tempers too and often undermined me with their arrogance.

Things could be quite aggressive, well organised and armed like a battalion as was obvious in large department stores where they sat armed with price tags, row upon row. When brought home, they demanded more and more of my attention and competed sourly with each other.

Things trapped me and wasted my time while I nurtured the illusion of possessing them. No, I did not wish to live with them any longer.

A communist in my youth, I often wondered if revolution would come when one day all manufactured objects united to overthrow the people, once for all. Then cars would no longer need to keep captive humans in their bellies with the windows rolled up because the air was not fit to breathe, they could just exchange manic grins with each other and move on, and refrigerators could belch and sigh contentedly without having their body temperature changed every now and then by the morbidly hungry and furniture could maintain its vanity and clothes their supercilious airs.

And yes, that burgundy cardigan. That came to mind.

I had been putting things together to be given away this season. That winter cardigan, burgundy, with drooping shoulders and an open front, two front-pockets to stick your thumbs into and strike a pose in, was a passenger ready for departure. For some reason I could not name, it vexed me.

I noticed how it tried to cling to other clothes hanging beside it, how it slid from the wooden hanger surreptitiously to land in oblivion at the bottom of the wardrobe where the shoes were stacked. Later, it became hard to locate on the pile on the bed, and yet again it slid out to the car floor from the plastic bags being carried to charity. There was plenty of resistance to leaving.

For all its years in oblivion, it should have welcomed the airing, the sunshine, this handling by warm human hands, being looked at. It was a handsome cardigan, originally meant for a male, but with the years it had lost its gender, become ambiguous, somewhat clouded. Not that it had lost all sensuality, the colour being that of sex and of veins cut.

It had a past, most surely.

It did not look quite new, of indeterminate age maybe like a man in his thirties, unsure of whether it was all over for him or only just beginning. You could imagine the sleeves rolled over for a sunny winter day of fishing when you fix the line to lie in the grass and look at the clouds scudding by; perhaps to roll a cigarette. The kind of cardigan you wore with corduroys and loafers to drive out in a Volkswagon jeep for a day in the sun or a night full of stars.

Did things remember happiness?

We never forget people we have shared our body with, so maybe the warm cardigan remembered other kinds of warmth -- the abrasive edges of bodies against its skin -- bodies that were firm, tall, worked out or if there was a belly to be buttoned away. The cardigan knew if the person who lived in it -- breathing in and out in such intimacy -- was agitated or if the energy percolated through him in an uninhibited spiral of sensations.

The cardigan had been without an occupant for so long it seemed to have forgotten its stories. It carried no contour or body odour. It forgot what it was a part of and how to use its life. In any case, it was not part of the vernacular dress code -- neither retro nor artsy -- but had assumed a dourness all its own.

Things can teach you so much. Like what it means for solitude to settle into your bones that weighs you down but also grounds you; things teach you to be nothing more than what you are, a stone among other stones. But for that you have to live an ascetic life.

Too many of things together and they gang up on you and make you in their own image, a purposeless object of luxury.

For all its years in confinement, the cardigan had long been released from any utilitarian purpose and ceased to be an idea in someone’s head. Was it free then or had someone just died? Did the cardigan kill its previous occupant to become skin and bone in droop and crease, reluctant to leave? Did it insist on being mine forever?

To share intimacy with things was dangerous; they could become part of your torment, part of the prayer.

Something behind me crashed. It sounded like a large wave breaking on the shore. Was this an underground thunderstorm rising to the surface? Would more waves arrive? The sparrows were now in a spin. The neighbour on my left started screaming and the red spread unevenly across her plump face. A man on the street was reading the kalma aloud and his inflexion on the Arabic was incorrect.

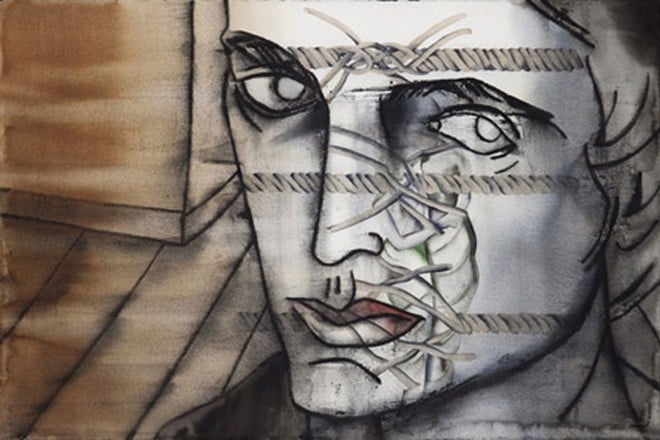

Still standing under the trees on soft ground, I could feel the clock ticking inside me get louder, more insistent, waiting for the crumbling of the picture plane.