In his lesser-known novel ‘Ayama’, Nazir Ahmad severely criticises the institution of Maulviyat

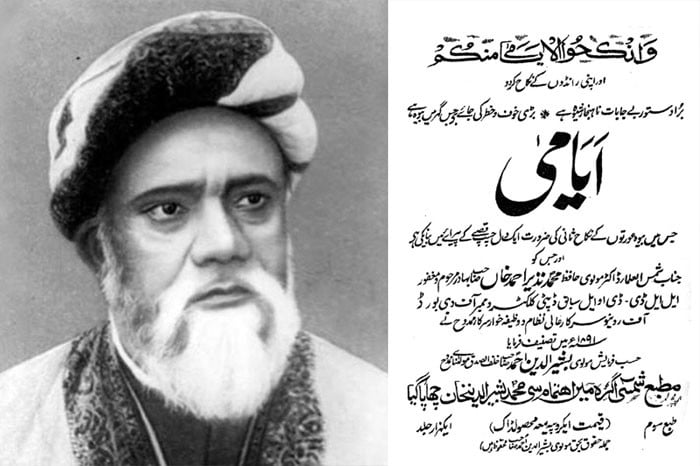

Ayama is apparently the last of Deputy Nazir Ahmad’s (1830-1912) published novels. The edition that I procured in photocopy -- third printing, 1000 copies, printed at Maktba-e Shamsi, Agra -- does not tell when the novel was first published, but its year of writing has been given as 1891.

I first came across its mention in Anis Nagi’s book, Deputy Nazir Ahmad ki Novel-Nigari (1988) and was duly surprised to see that neither the commercial nor the officio-ideological publishing houses that brought out the collected works of Deputy Sahib have cared to include this novel.

Another omission was that of Nazir Ahmad’s last book -- the infamous and twice-burned Ummahatul Ummah -- but perhaps that one did not require any explaining. When it was first published a few months before Nazir Ahmad’s death, it created a big uproar in the conservative religious circles and a vicious campaign was launched led by Maulana Abdul Majid Daryabadi who has made a name for himself as an undisputed leader of the North Indian Muslim witch-hunting squad.

Those who organised the publication of edited new editions of Nazir Ahmad’s works at the Majlis-e Taraqqi-e-Adab, Lahore, and the Majmooa Deputy Nazir Ahmad from Sang-e Meel Publications Lahore, did not find it necessary to say why Ayama has been singled out as the novel not to be reprinted. In fact, apart from the various editions published from UP and Punjab around a couple of years after Deputy Sahib’s demise, the book was quietly dropped from his works although all his other novels: Taubatun Nasooh, Mirat-ul Uroos, Binatun Naash, Fasana-e Mubtala (or Mohsinaat) and Ibnul Waqt have seen many editions since and have hardly ever been out of print.

Anis Nagi seems to be one of the few Urdu critics who studied and commented on Nazir Ahmad’s novels as possibly serious creative efforts in the history of modern Urdu fiction. Most other critics have been dumb and lazy enough to consider and label Deputy Sahib the equivalent of one of the main characters of his first novel -- Nasooh in Taubatun Nasooh -- and decided to eulogise or castigate him, considering their own cultural inclinations.

Related article: Before Night Falls is an unforgettable lesson of history

One of them has been so unbelievably naive as to blame the burning of Ummahatul Ummah on the Deputy Sahib himself, as a retribution to Nasooh making a bonfire of books of literature his son Kalim had been reading to get introduced to new ideas. The same set of critics have declared the protagonist of Ibnul Waqt to be a caricature of Sir Syed Ahmad Khan (1816-1898) and as such opened and shut the case of a very important Urdu novel.

What makes Nazir Ahmad’s novels interesting and significant is a continuous battle of ideas between and among his main characters; reminding one of the debates in the novels of Dostoevsky and Milan Kundera. Although even Anis Nagi complains of too much "behs-o tamhees", that, to me, seems to be the whole point: through his characters, upper-caste elitist, if not elite Muslims, Nazir Ahmad explores the effervescence of ideas that were being introduced ever since new education, change of hereditary professions, and printed word had become part of life of the modern North India. Nazir Ahmad could maintain his creative impartiality as he himself came from a not-so-upper-caste background and migrated from the provincial Bijnaur to the colonial capital Delhi to rise in life.

On the title page of Ayama, Nazir Ahmad declares it to be dealing with the religious and social need to allow Muslim widows to remarry. But, in fact, the novel, through its aptly named protagonist Azadi Begum, especially her life before her marriage and widowhood, deals with much more than that. The most significant of which being a severe criticism of the institution of ‘Maulviyat’ as a profession.

This and the status of a girl child and a young woman in a society in a flux are the two main themes Deputy Sahib explores with remarkable deftness and courage. While reading Ayama one feels, on the one hand, that the issues regarding the upbringing and empowerment of girls have been made to remain at a standstill in the previous hundred years or so, and, on the other, that the professional clergy still finds it a matter of life and death for their business to somehow keep women in chains of sickening traditions.

Like Nazir Ahmad’s previous novels, the characters and the plot are but vehicles to carry on the discourse -- as social discourse is what constitutes the body of his fiction. What makes the detailed and involved conversations in Nazir Ahmad’s novels -- not the least in Ayama -- so gripping and fascinating is the even-handedness that he can muster between conflicting perspectives.