‘Umrao Jan Ada’, a literary masterpiece and a bold experiment in political realism

The impact of a novel on a reader depends on both objective and subjective factors. The objective factor refers to the literary quality of the novel and its strength in terms of engaging the readers, subject to the condition that the reader is capable of appreciating at least the salient features of the narrative.

The subjective factor has to do with the reader’s age, mental development and capacity to understand the characters involved, their interplay and their journey (in terms of their thinking and behaviour) from the start of the plot to its end.

Thus, a good reader of fiction responds to a number of novels in his period of active readership -- few people other than professional critics keep reading novels in their old age at the scale they maintain till reaching the age of 45-50 -- (the case of people who start reading fiction only after retirement from their vocation is different).

For instance, I read Ratan Nath Sarshar’s Fasana-i-Azad when I was in 7th class and what I enjoyed most was Khoji’s comic interludes. At the same time, I read A. S. Bokhari’s (Patras) Saib ka Darakht, a translation of Hardy’s novel, which made little impact on me.

Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment and Brothers Karamazov made a considerable impact on me because my capacity to appreciate literature had improved somewhat. Then a new factor started affecting my response to novels. Novels that touched upon events and introduced characters with which I was familiar or with which I could relate attracted me more than others. That meant Khadija Mastur’s Aangan, Abdullah Hussain’s Udas Naslain and Mustansar Husain Tarar’s Rakh engaged me to a greater extent than Krishan Chander’s novels like Shikast that were greatly popular when I was young.

The object of this longish digression is to express my uneasiness in answering questions like "What personality has influenced you most?" or "Which novel left an impact on you?" The reason is that one is influenced by a large number of people, differently at different times, and the same applies to what one reads.

Read also: Goddamit -- why did I ever read ‘The English Patient’

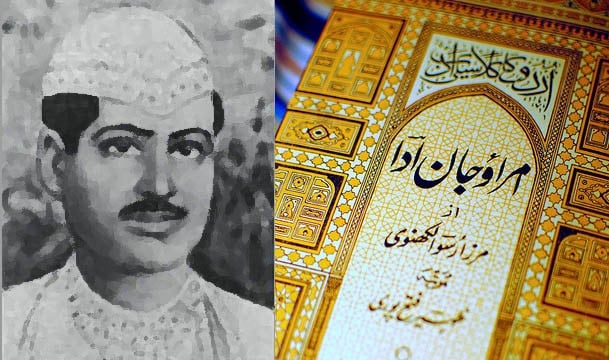

A good many novels, from Tolstoy’s War and Peace to Shamsur Rahman Faruqi’s Kai Chand thay Sar-e-Aasman made considerable impact on me. But, at the moment, I should like to say something about Mirza Mohammad Hadi Ruswa’s Umrao Jan Ada that made an immense impact on me. The reasons are as follows:

For reasons that are not relevant at the moment, I try to read a novel and its author (his life and his work before the book in hand) together, and I came to the following conclusions. Mirza Ruswa was a man of many parts -- overseer at civil works, teacher of Persian and Arabic, scholar of logic and philosophy, given to practical work in chemistry (al-Kemist), translator, poet, inventor of shorthand codes, and publisher of philosophical and scientific journals. None of this intrudes into Umrao Jan Ada and the novel offers us a new dimension of the author’s talent.

Mirza Ruswa had read many English novels and translated some in Urdu, and knew the contemporary form of the European novel. He borrowed something from the structure of the European novel and yet retained his link with the native tradition of Dastaan (Mir Aman and Rajab Ali Suroor). Thus, Umrao Jan Ada could be hailed as a novel rooted in the indigenous tradition and yet fit to be considered as the very first novel in Urdu by European standards.

Umrao Jan Ada is only the second novel by Ruswa and was written in great haste and under pressure to pay debts. To create a literary masterpiece while writing under stress reveals mental alertness of a high order and matching craftsmanship.

Written and published in 1899, Umrao Jan Ada can still be enjoyed by the present generation for it is a modern piece of writing not so much in terms of diction as in terms of its approach to the contemporary times and the characters. The novel portrays the Lucknow society as Ruswa found it and he paints it with great respect for objectivity. He chooses a prostitute to tell the story of his times because in those days only queens and prostitutes were allowed to speak in public.

But the spirit of the age and Ruswa’s own inclination prevents the heroine from being castigated by moralists. Indeed, Ruswa tries, quite successfully, to liberate the womenfolk and elevate them to the level of full members of society.

A matter of special interest for me in Umrao Jan Ada is Ruswa’s comment on the transition from a decadent monarchy to the British system of administration. He does not go berserk with paeans in praise of the colonial power -- as was the fashion in those days -- but confines himself to the fact that rule by princes’ whim and fancy had been replaced with a system of rewards on the basis of merit. A bit of romanticised liking for the new rulers notwithstanding it was a bold experiment in political realism. Hence, the novel is still alive.