Pakistan may have lost one of the most original and imaginative detective fiction writers, but what needs to be mourned more is the legacy of hatred left by him and others that is alive in the minds of millions of children of our times

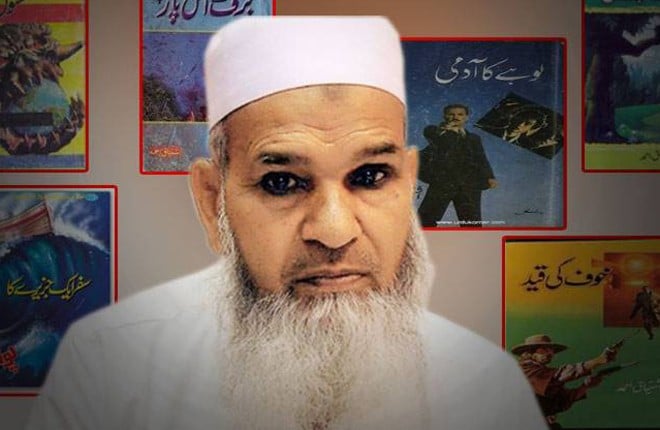

With the sudden demise of Ishtiaq Ahmed, an era of detective fiction writing in Urdu has drawn to close. A pioneer of a particular genre, Ahmed churned out close to one thousand novels. Like several other writers of detective fiction, he drew inspiration from none other but the legendary Ibn-i-Safi (1928-1980). But unlike others who, after Ibn-i-Safi’s death, capitalised on the popularity of his Imran Series and simply copied his characters, Ishtiaq Ahmed carved out his niche as an original writer. He launched his own series with Inspector Jamshed as its central character.

Associated with the police department as a detective, Inspector Jamshed was helped in accomplishing his missions by his children -- Mehmud, Farooq and Farzana.

The second series was named after Inspector Kamran Mirza. His character was different only to the extent that he was helped in his missions by his son, Aftab, along with Asif and Farhat -- his friend’s kids living with him. His most original series, and yet least popular, was that of Shoki brothers. Written in first person narrative, it was about four brothers running a private detective company. It had Ishtiaq Ahmed himself as the protagonist along with the rest of his real-life brothers Aftab, Ishfaq and Ikhlaq who collectively formed Shoki brothers.

For over two decades, Ishtiaq Ahmed captured the imagination of a whole generation of Pakistani children growing up in the turbulent period of 1980s and 1990s. Ahmed himself did not remain unaffected by these changes. Born in Panipat in early 1940s, his family had moved to Pakistan and settled in Jhang. Partition and the painful, drawn out process of rehabilitation must have had profound imprints on his personality.

More importantly, however, in the early 1980s, Jhang was emerging as the epicentre of sectarian violence in Pakistan. While the earlier novels of Ahmed did not show any explicit signs of religiosity -- or certainly not any extremist or sectarian tendencies -- things changed as he became a re-born Muslim. He was transformed into a staunch believer and an activist for the cause of khatam-i-nabuwwat, i.e. movement for the protection of the finality of Prophethood. This entailed joining hands with and lending support to organisations which were specifically involved in hate speech and persecution of Ahmadis.

Initially, he did not take up "religious missions" as a theme in his novels. He would simply advise his readers, most of whom were teenagers, to give priority to prayers, tasks assigned to them by their parents and do the home work before getting on to read the novel(s). But in his later novels -- more particularly in his special issues, or khaas number as they were called -- the teams of Inspector Jamshed, Inspector Kamran Mirza and Shoki brothers would combine to fight against anti-Muslim forces. One such remarkable piece (in terms of its imagination) was Yuda par Hamla which talks about a joint project sponsored by world powers to destroy a planet named Yuda causing threat to the existence of Earth.

As Ahmed’s detectives exposed towards the end, it was all a gimmick on the part of Western powers as Yuda was neither a planet nor a threat to Earth; they were actually planning to attack and destroy Moon. Without moon, the planners had estimated, Islam will come to an end as Muslims follow lunar calendar which is important, among other things, for the performance of many of their rituals.

Ishtiaq Ahmed’s novels surely had an impact on changing the worldview of his readers as well. A reader once asked him as to how could Farzana and Farhat work with men and boys who were not their mehram? In fact, how could Farhat live in the same house with Aftab and Asif when she was not their real sister? Another reader wondered if Kamran Mirza was actually a Mirzai -- a pejorative term used for Ahmadis or the followers of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad.

It is not the religiosity of Ishtiaq Ahmed but the turn towards extreme sectarianism which amazes me. How could he remain oblivious to the impact of his writings on young impressionable minds? How could such an imaginative mind be so full of hatred towards those with a different religious belief? In a way he was passionately driven to serve a cause. It is just that his idea of a cause worth serving was different from others. I also wonder if this has to do with the inglorious decade of the 1980s which changed his worldview.

After all it was not just Ishtiaq Ahmed who had started looking at every minor thing from a religious lens. This brings me back to the Imran Series of Ibn-i-Safi. In the original series and characters developed by Ibn-i-Safi, the members of secret service included Julia from Switzerland and Joseph from Africa. The most interesting aspect of Joseph’s character was that he was an alcoholic. Imran had to put him on a quota as he could not afford to pay for the quantity of booze he was consuming on a daily basis.

In the fake Imran series that followed Ibn-i-Safi’s death -- most popular of which is written by Mazhar Kaleem MA -- Julia converted to Islam and Joseph gave up drinking! The other famous series and its characters -- Jasusi Duniya with Colonel Afridi and Captain Hameed as the lead -- were developed during the pre-partition days. Ibn-i-Safi did not change the settings after he moved to Pakistan. He kept the cosmopolitan feel of his novels and characters alive.

Although he had never set foot in Europe, his depiction of its everyday life was incredibly close to reality. Again, after his death, an "Indian" Colonel Afridi was difficult for Mazhar Kaleem to handle who, thus, made him join the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) as head of its security and surveillance operations.

The 1980s has been a decade that witnessed the resurgence of religion throughout the globe. But the way it has captured the imagination of Pakistanis is beyond comprehension. While other societies seem to be gradually moving out of that phase, Pakistan is still trapped in the 1980s. More alarmingly, the intolerant legacy of 1980s has lingered on through a variety of mediums such as textbooks, Urdu newspapers and so on. This means that those who born in 1990s and 2000s are also being raised with a worldview which is intolerant and myopic and does not contribute towards fostering critical inquiry.

One enduring legacy of that period was Ishtiaq Ahmed. With his death, Pakistan has lost one of the most original and imaginative detective fiction writers. In our culture it is considered bad manners to speak ill of the dead. I mourn the death of Ishtiaq Ahmed, but what I mourn more is the part of my childhood, built upon the writings of Ishtiaq Ahmed among others, teaching hatred for others and persisting as a legacy which is still alive and kicking in the lives of millions of other children of our times.