Naseeruddin Shah’s play gives an insight into Albert Einstein’s compassionate side

Albert Einstein has just turned 70. That’s the time in his life when the play, titled Einstein, opens. It’s a time when one of the world’s most celebrated physicists who claims to be a "pacifist" and a "Zionist" is compelled to look back on days past.

Formally, the play is a long, extended monologue, in the tradition of a one-man show, with the main protagonist -- incidentally, the only character who appears before the audience; the rest are only mentioned in fleeting references or, as in the case of Elsa, Einstein’s second (and best loved) wife, or "Charlie" Chaplin (his friend), with a certain wistfulness -- reflecting on his life’s experiences that have impacted him in some way or the other.

But the play is clearly more than just a first-person account; it’s a little journey into the heart of an essentially simple man where you meet his loves, his peeves, his pet hates. It’s here that you get to see the compassionate side of a scientist who is gnawed by guilt because the very theories that earned him the title of a ‘genius’ are now being used to fight wars on humanity. "My creation is about energy, not bombs," he says, at one point in the play. On another occasion, he asks, "Killing is not a murder because it occurs in war?"

This remorse deepens, as the play moves on, amid references and cross-references to Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Germany, Einstein’s homeland that he gave up many years ago, the Nobel Prize that means nothing much to him, and his celebrity status in America that he has no care for.

You have to hand it to Canadian born, Jewish playwright Gabriel Emanuel for permitting the cult of Einstein a degree of everyday humour and vitality that saves this 20th-century script from becoming boggy at any given instant. Be it the genius’s deliberation that "socks are an unnecessary complication," or his rationale behind not travelling first-class -- "it doesn’t arrive any sooner!" -- or smoking ("The doctor forbade me to buy tobacco but not to steal it," he quips).

When he recalls how he was expelled from school because he would ask too many questions -- "or I looked like I was ready to ask questions"; his apathy to rote learning ("I hate to memorise!"); and that his teachers were like "sergeants," the audience is amused because it knows that Einstein had troubles with his school’s teaching methods but he was exceptionally good in mathematics and physics.

Meanwhile he is constantly reassuring himself: "I believe I am sane," he says, at the outset. Later, "It is never a mistake to question."

The bathos in his musings is unmistakable. Consider his apology to Newton for replacing his belief and for proposing that gravity is a field and not a force. And his final declaration, "Time is relative to the motion of the observer… One man’s now is another man’s then."

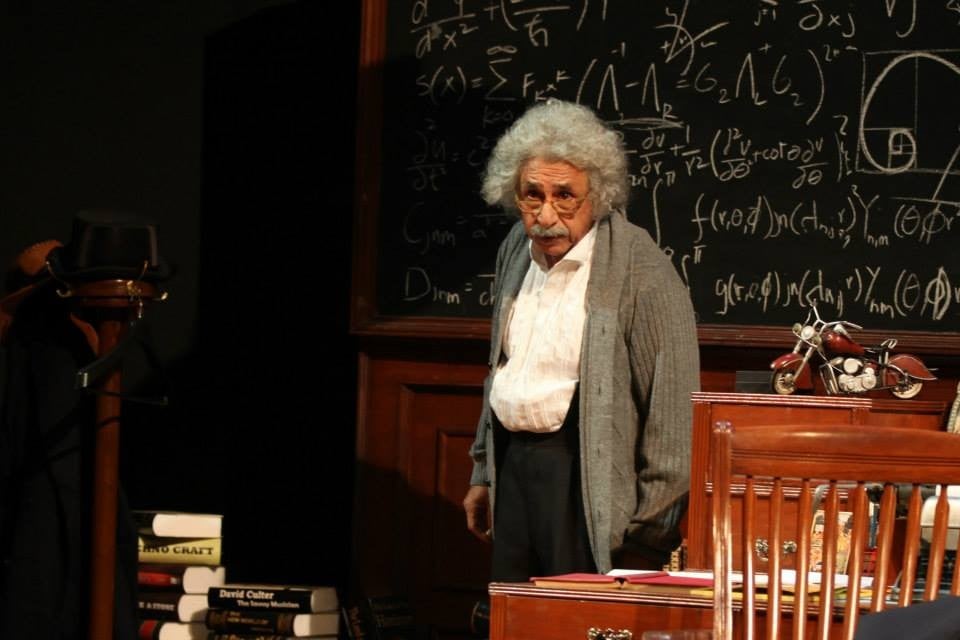

When the play opens, Einstein is getting ready to receive an award from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. His apartment room is stacked with books, a violin case, and a blackboard that is littered with scientific equations.

Barefoot and anxious, he shuffles through the clutter, sporting suspenders, ruminating on his life between puffs on a cigar and the dressing-up drill.

Portraying the Theory of Relativity’s highly feted creator whose multi-dimensional person is but lesser known, wouldn’t be an easy task for an actor. India’s Naseeruddin Shah brings the house down, literally, for not just showing a curious resemblance to Einstein but, more importantly, for slipping under his skin to a tee.

Like most solo shows, Einstein breaks the fourth wall that would conventionally separate the audience from the performer on stage. While Shah’s character addresses the audiences directly, he also pauses to interact with them in between. This makes for a delightful theatre.

The play is said to have been performed for the first time in 1985, in Toronto, and has since been translated into a number of languages and continues to be a favourite with theatre groups all over the world.

Perhaps, the only weak part of the play is that it lacks any major conflict which it would pivot on.

‘Einstein’ was performed and directed by Naseeruddin Shah, under the banner of his company Motley Productions, on the final two days of the recently concluded Faiz International Festival 2015, at Alhamra, The Mall, Lahore