Recent local government elections in Punjab and Sindh revived hope that Pakistan’s journey towards democracy will be successful

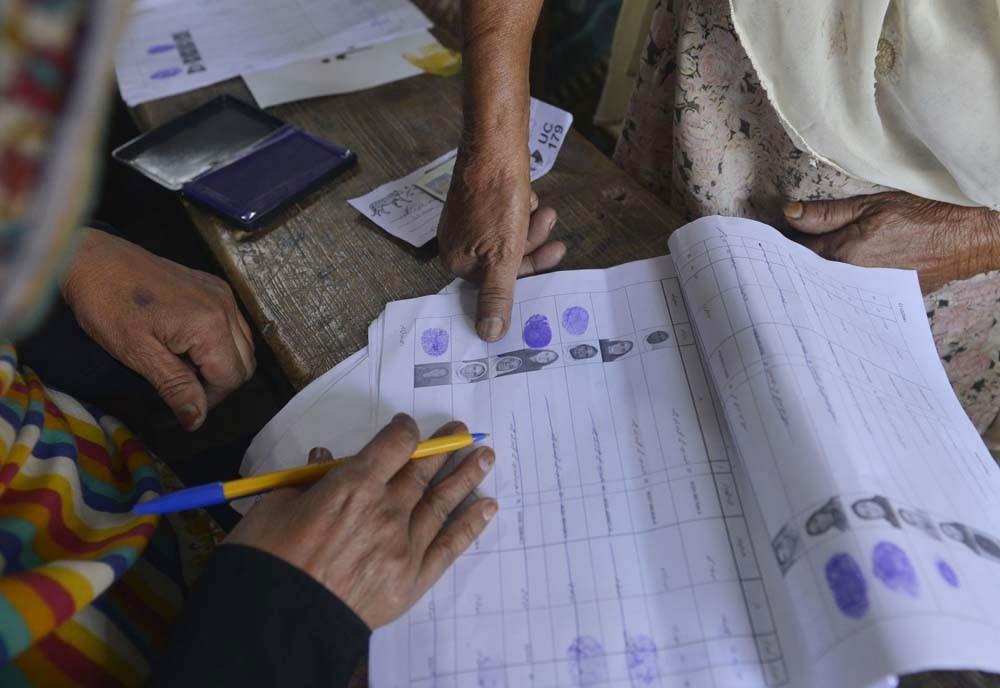

After many delays and talk of withdrawal from promises made, the first phase of local government elections concluded in 12 districts of Punjab and 8 districts of Sindh on Oct 31. A grand total of 55,971 candidates for offices of chairman, vice-chairmen, and general councillors contested the first elections for local bodies held in the country since the old local government system came to an end in December 2009.

Local government elections were last held in 2005 under General Pervez Musharraf, who came to power in a bloodless coup.

Prior reluctance to hold these elections can possibly overshadow the benefits of a newly revived apparatus. Bear in mind that only a few years ago the Nawaz Sharif government drafted a bill that planned to have local government elections on a non-party basis, when its rival Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf’s popularity was on the rise. Due to an intervention by the Supreme Court and former Chief Justice, Jawwad S. Khawaja, the elections were held on a party basis with the ruling PML-N proudly touting its ‘democratic’ credentials.

The successes of PPP in interior Sindh and PML-N in Punjab are not the result of ‘good governance’ in these respective provinces but a lesson in our home-grown politics of patronage.

Choosing to vote for the opposition and independent candidates not endorsed by the big power, or standing against a ruling party heavyweight in the election, is not a pragmatic decision. It translates into denial of resources including development funds available to ruling party office-bearers and the influence enjoyed over district departments. Candidates affiliated with the PML-N in Punjab had the clear advantage in assuring their voters that funds needed for repairing roads and dilapidated buildings would be secured from the provincial government. These grand claims were bolstered by the announcement of allocation of new funds for development work by Punjab government while the campaign for the first phase was still underway.

In spite of contrasting claims by federal ministers and, Chief Minister Punjab, Shahbaz Sharif, reports of mismanagement, including printing of wrong election symbols, late arrival of staff and skirmishes between rival groups from different cities and towns of Punjab and Sindh cast a long shadow of doubt on the credibility of the polls.

The polling stations at various places turned into battlefields as supporters of different participating candidates clashed with each other during voting time for the first phase of local government elections.

There were reports of various violations of the electoral procedures, breach of secrecy of voting, canvassing inside polling stations, and presence of security officials inside polling stations and incidents of interference by security and election staff in the voting process as well as occurrence of violent incidents in and around polling stations on the polling day. In this regard, the Sindh government’s decision to approach the judiciary to conduct an inquiry into the armed clash in Khairpur that left 12 people dead and another 15 injured, proved to be commendable with the Punjab government choosing to remain silent despite hue and cry from opposition parties questioning the polling process in the province.

Even as Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf revived its old habit of rebuking anything or anyone that stood in its way to the corridors of power, as seen in the press conferences by PTI leader Chaudhry Sarwar and its Punjab President Ejaz Chaudhry, it certainly deserved credit for holding the ruling party accountable for the most significant part of a democratic process. This is crucial for a democracy in its infant stages, in which autocratic tendencies of civilian and military leaders have ignored the need for electoral transparency and fairness.

The results were nonetheless shocking for the PTI and can offer a valuable lesson for the party in appealing to a disgruntled electorate. Unless the party reviews its current modus operandi, prospects of improving its political standing might wane to the advantage of a nearly extinct Pakistan People’s Party. A positive precedent was set by PTI leader Shafqat Mehmood, who resigned from his position as the party’s organiser for Lahore in local government elections after the party performed poorly in the first phase in Punjab. That PTI chief Imran Khan has sought a report from his party members on the defeat is a positive development on this front.

For both the PML-N and PTI, the victory of independent candidates, this time around winning more than 1000 seats in Punjab and Sindh, offers a moment for the parties to look deeply into their credentials. In the recent by-polls in Okara, an independent candidate won the seat by defeating the PML-N and PTI candidates. It is possible that the voting public is tired of the same old rhetoric and sophistry.

A group of 20 Christian organisations and parties called the ‘Pakistan Christian Alliance’ boycotted the first phase of elections protesting against the allocation of minority seats in union councils through political parties’ nominations. Representatives of this alliance in interviews with the press lamented that minority members of parties were marginalised in the electoral process. Notably in UC-245 and 246 (Youhanabad), both Christian working class neighbourhoods falling under Chief Minister Shahbaz Sharif’s constituency, the community fielded and voted for its own independent candidates. After the twin church blasts in March this year and the subsequent harassment of Christian youths by Punjab police, a sense of alienation from mainstream political parties led to this significant decision.

Undoubtedly, democracy is a grassroots exercise; the most representative form of government is institutionalised at the level of local communities. For much of its 65 year history, democracy in Pakistan has been a top-down affair with a small group of dynastic elites retaining as much power and resources as they can possibly maintain without falling from the top.

In lieu of this, it is a welcome development that by the end of December 2015 the whole country will have a fully functional local government system, albeit with flaws. The more power is shared by and among elected institutions, the more difficult it will be to sabotage Pakistan’s journey to true democracy.