Mohammad Afzal Khan was an idealistic politician and an author with big ideas. He didn’t achieve most of his goals, but he never stopped struggling and saying things that he considered right

His name was Mohammad Afzal Khan, but he was commonly known as Khan Lala.

Being a prominent landlord from a family with the right pedigree, he was certainly a Khan. However, it was the title of Lala that he rightly earned and deserved as someone older and wiser. Khan Lala was like an elder brother to everyone. One didn’t feel like calling him Afzal Khan as Khan Lala sounded and felt better.

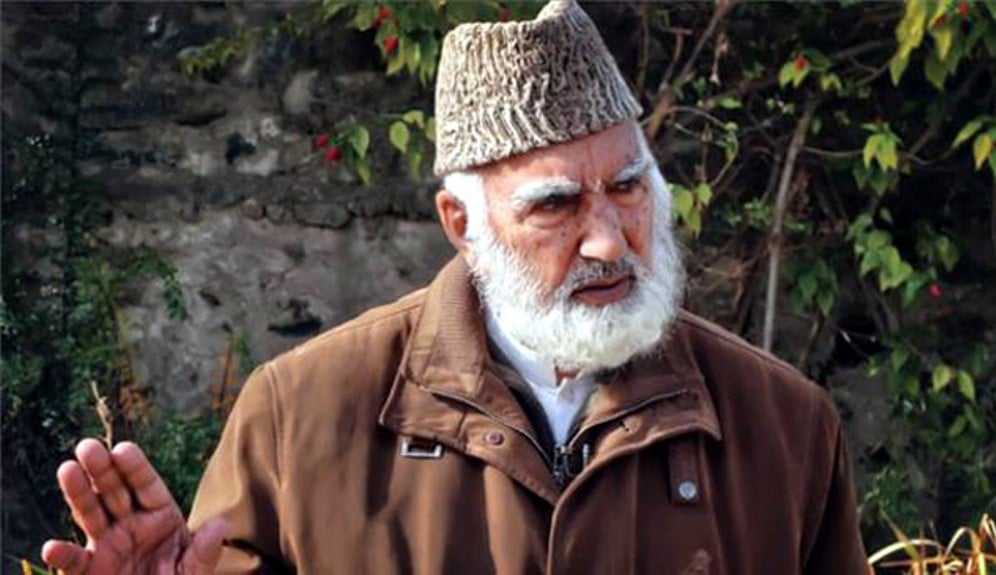

Khan Lala was 89 years old when he passed away on November 1, but his appearance as a white-bearded old man hadn’t changed all these years. His face was forever friendly and his talk was always familiar. The thought that he is no more is both strange and painful.

At his picturesque village Bara Drushkhela in Swat’s orchards-laden Matta tehsil, one saw a steady stream of mourners arriving to offer Fateha for the man who despite his old age stood his ground at this very place when the Taliban were rampant and feared. Though he had lived all his life in Swat, the last decade or so was the toughest and most dangerous because he had challenged the Swati Taliban in their stronghold at a time when most other politicians and notables were leaving their ancestral land and moving to relatively safe places such as Peshawar and Islamabad. Survival was the name of the game, but not for Khan Lala as he had already survived attempts on his life and attack on his house.

The term chivalry aptly applied to this veteran Pakhtun nationalist who lived by the code of honour of Pakhtunwali. He was both humble and fierce depending on the circumstances. For years he championed the cause of the Pakhtuns and advocated unity among the "lar and bar Afghans" living in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

However, he wasn’t anti-Pakistan and had, in fact, joined hands with the state to fight against the anti-state elements when Swat almost slipped out of control of the government in 2007-2009. His close relationship with the military also underscored his love for Pakistan even though some nationalists found it uncomfortable and intriguing. However, the precarious security situation in Swat at the time left no other option for Khan Lala, but to come close to the only organised force that mattered in the face of the onslaught by the Maulana Fazlullah-led Taliban.

The Pakistan Army also gave the highest regard to Khan Lala as long as he lived and even after his death. It flew him from the Saidu Sharif airport, which after years of disuse was made operational in the wake of the recent earthquake, to Rawalpindi and got him admitted at the Combined Military Hospital for treatment of liver cirrhosis. And when he died the next day, his body was flown home to Swat for burial. Corps Commander Peshawar Lt Gen Hidayat Ur Rahman and General Officer Commanding Swat, Maj Gen Nadir Khan led the army officers who attended his funeral.

It is obvious the military would have played a role when the government in 2009 awarded Khan Lala the Hilal-i-Jurat (crescent of courage) medal, the second highest civil gallantry award in Pakistan. He was honoured by the army by inviting him to events organised by it and generals, brigadiers and colonels operating in Swat sought his advice. Soldiers were deployed at his village to reinforce his armed volunteers when the threat by Taliban fighters to Khan Lala and his family peaked. It helped that his son and nephew had served in the army.

During his long political career, Khan Lala mostly remained on the opposition benches. He briefly remained part of the government in the 1970s and 1990s, but one never heard any scandal or corruption attached to his name. His politics was spotlessly clean, just like the white shalwar-kameez that he preferred to wear.

After winning election as member of the provincial assembly from Swat in the 1970 general election, Khan Lala became a minister when there were only three ministers in the coalition government of Khan Abdul Wali Khan’s National Awami National Party (NAP) and Maulana Mufti Mahmud’s Jamiat Ulema-i-Islam (JUI). This explained his seniority and importance in the NAP, which he also led as the provincial president in 1978.

He also served as a federal minister, but then he wasn’t part of the original NAP (and its successor ANP), as he had quit after developing differences with the leadership over the direction of its policies, including its decision to form an alliance with the conservative Islami Jamhoori Ittehad. He and some of the progressive elements had broken away and formed the Qaumi Inquilabi Party to eventually join hands with the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) and contest from the platform of the PDP in the 1993 general election. The polls brought him victory as the MNA from Swat and he was made federal minister in Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto’s government from 1993-1996.

It was during this period that he referred to the North-West Frontier Province (NWFP) as Pakhtunkhwa in the National Assembly to trigger a storm of protest from scores of lawmakers. This was the first time that a lawmaker, and one serving as federal minister, had used this term for his native province in the parliament. Khan Lala had the courage to utter Pakhtunkhwa in the face of fierce criticism without backing down. He was vindicated after the 2008 general election when the ANP persuaded both the PPP and PML-N to back the constitutional amendment for renaming the NWFP as Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and giving identity to the Pakhtuns.

Political considerations became a hurdle when a proposal was floated to make him the governor of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. The military would have backed his candidature if his own party, ANP, had pushed it. Though Khan Lala had returned to the ANP after their brief separation earlier, he was no longer in the inner circle of the party leader, Asfandyar Wali Khan. He had even complained that he wasn’t consulted when the ANP was in power in the coalition government with the PPP in the province and had negotiated despite his opposition the failed peace agreements first with Maulana Fazlullah and then with his father-in-law Maulana Sufi Mohammad.

Khan Lala also suffered on account of his political views as he faced imprisonment and persecution. He and the top NAP leaders ranging from Wali Khan to Ghous Bakhsh Bizenjo, Nawab Khair Bakhsh Marri and Sardar Attaullah Mengal were jailed in Hyderabad for three years and their party was banned by Prime Minister Zulfikar Ai Bhutto’s government. The next ruler, General Ziaul Haq, dropped the treason case and freed them in 1978.

Later in life, Khan Lala had stopped contesting elections and for a while aligned with the shortlived Pakistan Oppressed Nations Movement, which advocated giving maximum provincial autonomy to the provinces and the different ethnic groups.

Khan Lala was an idealistic politician and an author with big ideas. He didn’t achieve most of his goals, but he never stopped struggling and saying things that he considered right.