There is hardly any project in the education sector that pins down poverty as the root cause of massive dropouts and tries to solve it. Alif Ailan selects one district in rural Sindh for local level data collection and analysis and produces an excellent report

The hapless education sector in Pakistan is fortunate in at least one aspect: despite a pathetic record of low government spending on education, international donors have put in money in this sector with zeal. That not many donor-funded projects have produced sustainable results can be attributed to not only bureaucratic inefficiency but also to donor ill-planning.

Having spent quarter of a century with the education sector, one can claim that most donor-funded projects fail mainly because they are, to a great extent, concerned with the macro picture. Projects are formulated based on erroneous conclusions; sweeping statements are made from observations through telescopes rather than microscopes. Most proposal writers have scant understanding of the districts where their project would try to introduce some change.

It is with this background that Alif Ailaan’s recent report on local education data should be seen. Alif Ailan is a UKaid-funded project that appears to be different from other projects for its appreciable stress on producing and analysing local i.e. household and community-based data for education interventions. Ideally such data should be collected from all communities across the country; and as a first step Alif Ailan selected Thatta in Sindh for local-level data collection and analysis.

Though Thatta is hardly a hundred kilometres away from Karachi, it remains one of the lowest performing districts in Pakistan, and the worst in Sindh. Normally you would expect a remote or far-flung district to be performing worse than an easily accessible district such as Thatta, but here probably no logic can be applied.

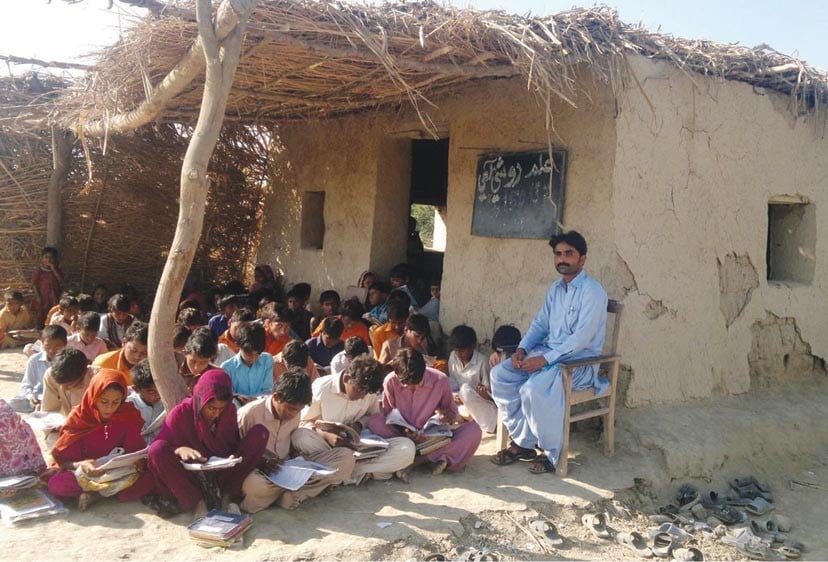

No matter what measure of a good education system you select, Thatta appears among the lowest. Despite Sindh government’s claims to the contrary, hardly any tangible action has been observed to fix education at the level of schools and communities. Sindh Education Management Information System (SEMIS) collects and maintains data from schools across Sindh, but these data are seldom used for policy decisions such as recruitment of teachers and fund allocation. Moreover, the data analysis within districts and communities is missing and SEMIS data don’t help us to understand why enrolment and retention ratios are low and why the quality of education is hitting the rock bottom in certain communities.

Alif Ailaan report appears to have done well by highlighting the diversity of local contexts because only by including local issues in policy responses the challenges of low enrolment and retention can be tackled. Since the available data sets are usually not robust, it is always useful to triangulate the data. For this report, triangulation was done for both primary and secondary data sources, and the result is startling: in the entire district of Thatta, two-thirds of all the children were found to be out of school that means only one in three of the district’s children go to school. For girls, this is even more disappointing. In union councils such as Keti Bundur, Mirpur Sakro, and Gharo, as many as over 70 per cent of girls are not enrolled in any school, and most of them have never gone to school.

Talking about barriers to schooling, the most prominent appears to be the government’s supply of schooling; to achieve 100 per cent schooling over 53,000 children need to be enrolled and for that nearly 20,000 households need to be empowered so that parents are able to send their children to schools.

What most other education projects overlook is that the parents’ inability to send children to schools is directly related to extreme poverty levels prevalent in these communities. This poverty results in malnutrition that is alarmingly high with more than half of the children in Mirpur Sakro being stunted, every third child being underweight and every fourth showing signs of wasting. The report highlights the fact that this malnutrition is a direct result of the poor diet that pregnant and lactating mothers usually have and that results in children lacking essential nutrients.

It is surprising that the correlation between poverty and the inability of parents to send their children to school is so conveniently overlooked by most policy makers. Numerous surveys have been conducted to understand why children are out of school and they reach roundabout conclusions, they pinpoint lack of interest among parents and cultural barriers but fall short of talking about poverty issues.

Malnutrition is not something caused by the parents and communities; it is the result of a prolonged maldistribution of wealth in society. How can donors brush aside the fact the even if you train teachers and renovate schools, a family will not be able to send children to school if they don’t know where their next meal will come from?

The data collected through surveys are not always valid and reliable. In this particular case, it is important to note that the Alif Ailaan report used school and household censuses. A survey generally relies on a sample whereas a census tries to capture every unit of analysis be it a household or a school. This census in Thatta confirmed that ghost schools are far more numerous than those recorded in the government data. Can you believe that in the 21st century Sindh, half of the government schools in eight union councils of Thatta are closed but all private schools are open?

More than half of enrolled children in urban areas attend a private school but almost all those who attend a school in rural areas go to a government school. Though officially there is a ban on corporal punishment, more than a quarter of parents in UC Mirpur Sakro said that their child had been beaten up by his or her teacher at school. Almost a similar number simply don’t want to go to school for fear of corporal punishment.

Probably the most obvious point that needs to be projected again and again is that communities are different in nature of their circumstances; the more glaring it is, the more it appears to be missing from policy makers’ and project managers’ sight. One prominent reason why education projects fail is perhaps this one-size-fits-all approach where project managers with some experience in sub-Saharan Africa or in some South Pacific islands are deemed to be proficient in education management across the world. Though the development literature is replete with examples of failed projects just because of an inappropriate focus, even now one finds projects with misplaced stress on fancy words.

Alif Ailaan’s focus on local data has once again proved the point that communities have different sets of needs and priorities for education reform. The mantra of hiring more teachers and building more schools suits those who have a stake in it. If you talk about reducing poverty and malnutrition, there are fewer chances of obliging political favourites, hence it becomes convenient to overlook these issues. Without sound and robust local data, the decision makers can easily hire more teachers even if there is a glut of teachers in a particular area and give contracts for more school construction where there are already three schools on paper alone i.e. ghost schools.

There are hardly any projects in the education sector that pin down poverty as the root cause and try to solve it. You will come across projects focusing on school management committees where there are no literate parents; on computer labs where there is no electricity; on toilets where there is no water; on furniture where there are no doors; and on lab equipment where there is no lab or even a science teacher. Why? Simply because no household and community-level data are available. And in that sense Alif Ailaan has done a commendable job.

Simple data collection about government schools is not enough, what we need is comparable data for both government and private schools. Most government data are inconsistent especially if you want to look for a particular trend. So far as private schools are concerned, the data are conspicuous by their absence. Similarly, the data about madrassas are either incomplete or non-existent. The report rightly points outs that a robust and systematic data collection and analysis mode is needed that goes beyond maintaining records about schools that are neither triangulated not validated.

Another astonishing revelation by this report is about the number of non-functional schools in the eight union councils across Thatta: out of a total of 444 schools 213 schools are reported to be closed; even according to the government data every fourth school is closed, but as per Alif Ailaan report 48 per cent schools are closed that means almost every other second schools is non-functional.

The report rightly suggests that probably the only way to address this problem is to force public representatives and government officials to send their children to government schools where every other school is closed and even the so-called functional schools lack basic facilities such as drinking water, functioning toilets, and electricity; only then will they be seriously willing to address people’s problems of this nature.