Free from any commercial concerns, Sangat theatre continues to thrive. The people behind the group have also reversed many practices of traditional native theatre

Some years ago, I had a chance to see Huma Safdar’s brief, dramatised version of Heer Waris Shah at a local branch of Lahore Grammar School. As a serious student of Waris Shah, I had imagined the possibility of dramatising it but never imagined the scope that this production showed.

Safdar’s genre beat the age-old Heer singing tradition. Waris, it seemed, had written the tale to be performed. This performance was a revelation. What a production and what a playwright our bard was, I thought.

For the uninitiated, Safdar is a qualified painter, who is known to have been a student at the National College of Arts, Lahore, during Zia’s repressive regime. As a teacher at LGS, she has been associated with some of the most remarkable stage productions for over 20 years now.

Both Heer Damodar and Heer Waris Shah had been performed earlier also but those were never text-based; there would be improvised snippets of dialogue with an occasional, original passage thrown in.

A masterful director, Safdar has grown with experience. Having put together Mian Mohammed Buksh’s Sohni and Hashim Shah’s Sassi, besides a number of playlets by Najm Hosain Syed, with school girls, she went on to produce plays with a repertoire team of her own.

Comprising predominantly ladies from Syed’s Sangat, together they performed a number of his playlets as well as the five-and-half-hour long marathon play, titled Alfo Perni Di Vaar. Later, they toured East Punjab and earned kudos there.

Even with this remarkable record, I must say Huma Safdar outdid herself with Heer Waris Shah that was performed on the occasion of Mela Chiragan at Takia Bohar Ala near the Pakistan Mint.

I remember sitting with the Heer singers who were waiting for their turn. They seemed thrilled to bits. They would repeat dialogues which they seemed to know by heart, and cheered at every passage spoken or sung on the stage space.

I have studied Heer for over forty years, under the tutelage of masters like Sharif Sabir Sahib and Najm Hosain Syed. Yet, Safdar’s play was a different experience altogether. Heer (played by Uzma Ali) and Ranjha (Ali Sher) naturally took centre stage but even bit parts like Shepard who confronts Ranjha (Faheem), Qazi (Shafquat) who forcibly marries off Heer, and Heer’s mother (Kanwal) were very well essayed.

A repertoire group grows and improves with experience. But how much, I only realised when I saw their next performance at Olomopolo recently. Better lighting and acoustics and the well designed (albeit smallish) hall made it an intimate affair, combined with a show of histrionics by the performers. (They, I was told, had been holding weekly acting workshops to hone their skills.)

In a rather small part, Naeem’s Shephard excelled. But, as I found, Heer Ranjha’s love story had also moved on, and passages added to the original. Uzma Ali, who is also a trained classical dancer, looked the quintessential Heer as she spoke her lines, emoting ecstasy and agony with the rhythm of her body. The sophisticated audience was just as appreciative as the crowds of common people I had seen at Takia Bohar Ala.

I had written in my previous column that Huma’s group is about the serious business of theatre rather than the fakery prevalent in Lahore theatre today.

Waris Shah and its stage performances may be a novelty for most town dwellers but a recent tour of Huma Safdar’s group to villages in South Punjab had the country folks equally impressed. With 20-odd performances in small towns and villages, both the performers and the audiences surprised each other with their involvement. On one occasion, while the group was resting under a large ‘bohr’ tree, some women gathered around and asked them what they were doing there. The group people not only told them about their mission but also enacted something on the spot. That is what a traditional touring theatre is about -- it is ready to perform.

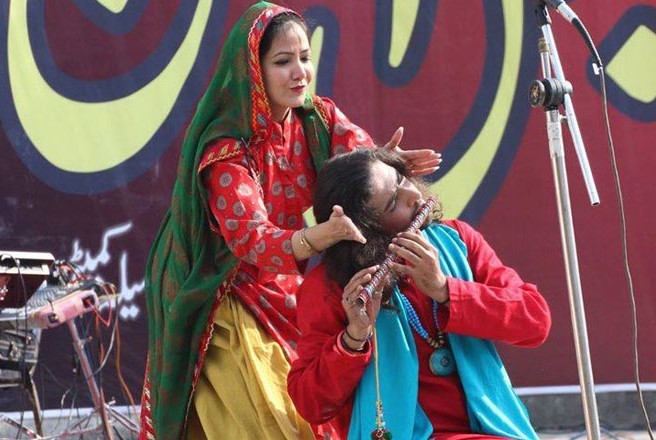

Free from any commercial interests, the Sangat theatre continues to thrive. The people behind the group have also reversed many practices of traditional native theatre. For instance, the traditional theatre had males performing female roles, for obvious reasons; here, girls often take on the men’s parts. It has to be seen to be believed.