Romesh Gunesekera recounts stories built on faith lost in the melodramas of grievance and revenge enacted during the Sinhalese-Tamil Civil War and the religious enthusiasm for gods, paradise, and martyrs

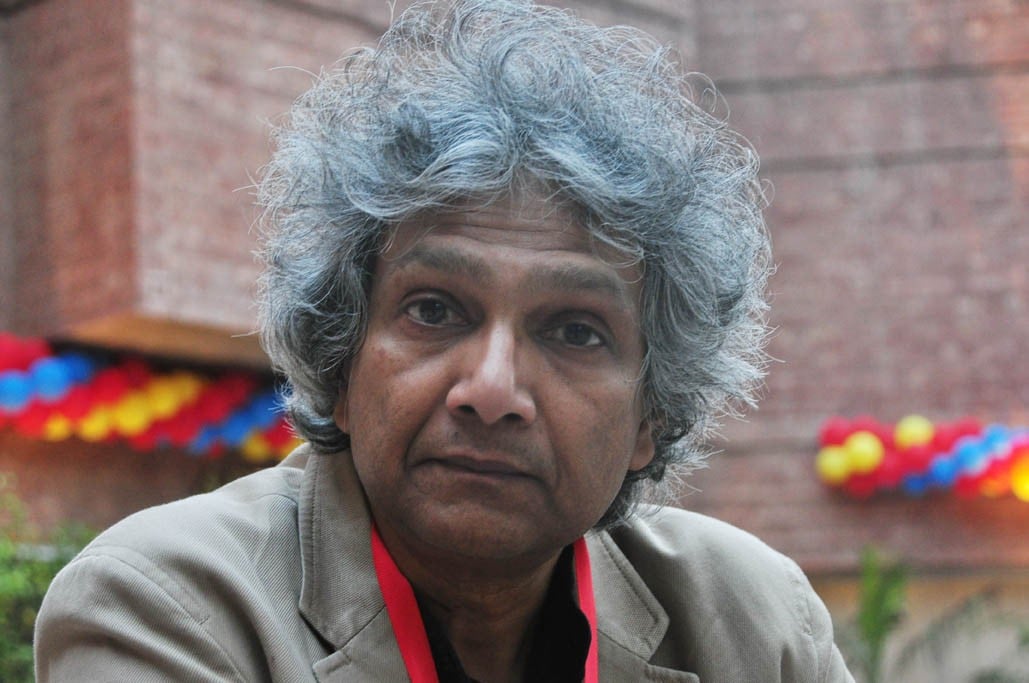

Romesh Gunesekera is a simple man of gentle wit and great learning, a kindred spirit with impeccable manners. Born in 1954 in Colombo, Sri Lanka, he went to an elite Sinhala school when "English was seen as the sword that cut off people’s mother tongues." Following his father to the Philippines for five years, he returned to England where he began writing at the mere age of 15. After studying English and Philosophy at Liverpool, he moved to London in 1976. While serving as a senior official at British Council Headquarters, he continued to write for 12 years until he became a full-time writer in 1996.

The cast of characters in Gunesekera’s tales cannot reconcile the beauty of the world and the joy of the senses with the demands of renunciation; or reconcile the demands of humanity with the fear of entrapment in the vast network of illusions. They find themselves staring at blank spaces in which identities are utterly confused. Caught between rational knowledge and uncontrolled passion, religious faith and despair, they wait for the seasons to turn. There is no nostalgia in Gunesekera’s novels -- only a profound sorrow and a hopeless longing for a world different from the one created.

Aspiring for a complex and pluralistic wholeness, Gunesekera recounts stories built on faith lost in the melodramas of grievance and revenge enacted during the Sinhalese-Tamil Civil War and the religious enthusiasm for gods, paradise, and martyrs. Below are excerpts from a conversation held on the steps of Alhamra in Lahore.

The News on Sunday: When did you start writing?

Romesh Gunesekera: My writing started much earlier than Monkfish Moon, probably when I was fifteen or sixteen in the Philippines, before I went to England. (Prior to that when I was living in Colombo, I wasn’t really interested). I was very interested in writing imaginative prose as well as poetry, but I tried getting published as a writer much later in my twenties after having beenwriting for some time. In the late 1970s, I was trying to get my poems published but the early poems had to wait until the 1980s. Around the same time, my early stories came out in magazines but I didn’t have a book of any sort. When Granta agreed to publish my fiction, I decided to write a specific book of stories, and that’s how Monkfish Moon came about - out of individual stories. Although they were not connected stories, they were somehow connected by the fact that they were to do with Sri Lanka. One or two were even based on Sri Lankans in England.

TNS: Having lived away from Sri Lanka practically your entire adult life, is it for reasons of nostalgia that Sri Lanka forms the ubiquitous backdrop in nearly all your books?

RG: The setting of my novels has always been Sri Lanka not out of nostalgia because I sense my relationship with Sri Lanka grew through the writings more than anything else. I got interested in writing stories because I felt it was an unexplored territory. Sri Lankan writing in English or imagined Sri Lanka in English began quite a long time ago, the first novel ever written in English with a Sri Lankan backdrop being the one by Leonard Woolf -- husband of famous Virginia Woolf. (He was a district officer in Sri Lanka but wrote the book in Bloomsbury after he came back to England). It’s a very interesting book, and is significantly different from the Forsters and the Kiplings. It’s a book in which all the characters are Sri Lankan except for one very minor character of an Englishman, and it’s probably been the best book on rural Sri Lanka in English for a considerable time if not even now.

I had not read any of these books; I had read books set in other parts of the world, and therefore, wanted to create an imaginative Sri Lanka that I understood or knew. Reef, to begin with, was not intended to be that sort of book. In the subsequent novel, The Sandglass, I wanted to explore the Sri Lankan background partly but its main interest has had much more to do with mortality.

There are three books of mine in which Sri Lanka is peripheral: Heaven’s Edge does not claim to be set in Sri Lanka -- one can even read it as a Sri Lankan dystopian novel; The Match just has a very small section on Sri Lanka but has some important Sri Lankan characters; and Prisoners of Paradise, my last novel, is set in Mauritius. My answer for Sri Lankan characters is simply that they seem to speak to me best, and I am interested in exploring them. It’s a discovery for me, and a continuing exploration.

TNS: Which of the characters that appear in your novels is modelled after you?

RG: None of them is, and that’s quite deliberate. I am not an autobiographical writer, and that’s partly because my actual published writing came quite a long time after I had started writing. I think as a writer, you have to identify with most of your characters; you have to have an empathy with them. My characters are close to me in that sense, but at the same time, any fictional writing becomes your autobiography to some extent more than the other way round. The settings in my book, The Match are autogeographical rather than autobiographical. Sunny Fernando, in that book, travels the same journey as I have travelled. And that was quite deliberate for two reasons: one because in my previous book, the setting was an invented place in history and I wanted to write a book now in which I didn’t have to invent the chronology and the geography; second because I wanted to create some imaginative fiction set in the Philippines. The places in the book were known but the characters and what happens to them, wasn’t.

TNS: Why have the tugs of Sinhala-Tamil Civil War been central to all your narratives when you haven’t experienced them first-hand?

RG: I don’t really set out to write ‘literature of war’. I am exploring characters -- it just so happens that the world has turned into a world of war. In some respects the world is actually less violent than it has been in previous centuries, but in other respects, it has been a continuous war in twentieth and twenty-first centuries. But that’s the world we have and that’s what I am writing about.

Both Orwell and Conrad are quite important to me, partly because of their use of language. Orwell is interesting because of his speculative fiction and the particular perspective he has on the world. We all live in an Orwellian world, which is extraordinary when you think that a novel has managed to give us the perspective that we have followed in many ways: the language we speak, the doublespeak we use, even the geography we employ. One of the reasons why I wrote Heaven’s Edge is because it was an attempt to deal with speculative fiction and see if that could make a different kind of novel. In fact, while writing another novel, I happened to be geographically on the Scottish island of Jura that Orwell wrote 1984 from. So, there’s a curious link there.

Everything I’ve read feeds into my writing. I could think of William Faulkner and Thomas Hardy -- both used an imaginative landscape in their writings. To some extent, my relationship with the imagined Sri Lanka of my novels is very similar.

TNS: How do you respond to the notion of ‘Island Writing’?

RG: You can have categories of writing of all sorts, and they are fundamentally arbitrary. You can categorise writing by geography; you can categorise by period or you can even categorise writing by culture, but these are all artificial. The only category that might have some fundamental sense to it is language. I think it was E M Forster who said that the worst way of looking at fiction is to categorise it by period. Basically, he was really against the idea of any such thing as a Victorian era of novels, etc., and I have some sympathy with that. You can’t write a novel without acknowledging novels written in Russian or novels written in Spanish. These are the roots of literature -- the genre in itself is more important!

When it comes to Island Literature, what are its distinguishing features? And I suspect there aren’t any, just as there isn’t a distinguishing feature of South Asian writing. Some writers have told me that the South Asian novel is this epic, sprawling ‘thing’ because that’s what India and Pakistan are -- they are big places and they need big novels to capture them. Yes, there are big novels but R K Narayan and Manto who can capture things in small ways. In fact, in Sri Lanka too, there are writers who have written huge historical books.

The other way of looking at it is what is an island? You could argue that islands can be very large like North America, Australia, Europe and Asia. What I do like about the idea of islands is that islands are an interesting idea. And islands are where things happen. Even an oasis is an island. And indeed if we go further, we can say that even planet Earth is an island. But, in my view, even more interesting than that is the notion that a book is an island. That is why we need stories and novels because they are ways in which we go to an island, to a place bounded only by the boundaries of a story either within a story itself or within the physical structure of a novel.

No man is an island because we are interconnected. There’s a deep philosophical argument that you can have your own language as a single person. In my view, there’s no such thing as a private language. It has to have communication that requires two entities. The written language works the same way. What is a novel? It is a conversation, a long cultural conversation, which the planet is having with itself through different languages.

TNS: Cricket and photography feature large in The Match. How did these two parallel themes evolve in a single novel?

RG: I did happen to look at Julia Margaret Cameron’s photographs while writing that book. I was very conscious of what she was trying to do, and I am very interested in the whole notion of photography and what it is in terms of its art form. The fundamental aspect of it I am interested in is its relationship to time as opposed to the relationship the novel has with time. They are very different: As I say in The Match, Cartier-Bresson’s idea that photography is a way of capturing time and stopping time. To some extent, the novel is a way of both capturing time but also escaping from time. If you go back to the notion of language, the reason written language was invented as opposed to oral language was to defeat time. That was the primary purpose so that you no longer had to rely on meeting someone to communicate. You could write it, and escape the barriers of place and time.

If you could recall how it started, it was obviously for counting purposes and trade but the notion was that you could record what happened at this moment and have access to it when you are somewhere else. So you are both escaping but also capturing time.

So I was very interested in the two art forms and the two ways of looking at the world. And also the truths that are involved in it. It is now slowly we have recognised how ‘untrue’ photography is -- even before the current age it had become ‘untrue’ because you could totally doctor everything! But right from the start of photography, it was not capturing reality but something else. If you look at the photographs of the American Civil War, these are composed pictures. In case of Cameron, I am very interested in that period of photography and what it does to our knowledge of the past.

Most of us have an image of the past particularly of nineteenth century South Asia which feels very still and calm. And it still is calm from the images we have from photographs. And the photographs are calm because the technology could only capture things stopped. You don’t have the sense of the bullock cart moving because you’ve never seen one but you have seen still pictures of it. And that has coloured the way we look at it. In a way everybody knows that it’s very curious how we remember people of a certain age, remember their childhood in black and white rather than in colour.

The cricket part of it was quite deliberate: I wanted to write a novel that had an element of cricket in it partly because there hadn’t been any before. I’ve been writing about Sri Lanka with this rather tragic war as a backdrop, the more positive story of Sri Lanka has been its story of cricket, from the 1990s onwards. I wanted to capture that dimension, that aspect in a novel.