A peek into history to understand how and why National Awami Party was persecuted and banned

October is an interesting month in the history of Pakistan; from the dissolution of the first Constituent Assembly in October 1954 and the imposition of the first country-wide martial law in October 1956 to the landmark decision of the Supreme Court in October 1975 to uphold the ban on National Awami Party (NAP) imposed by the Bhutto government.

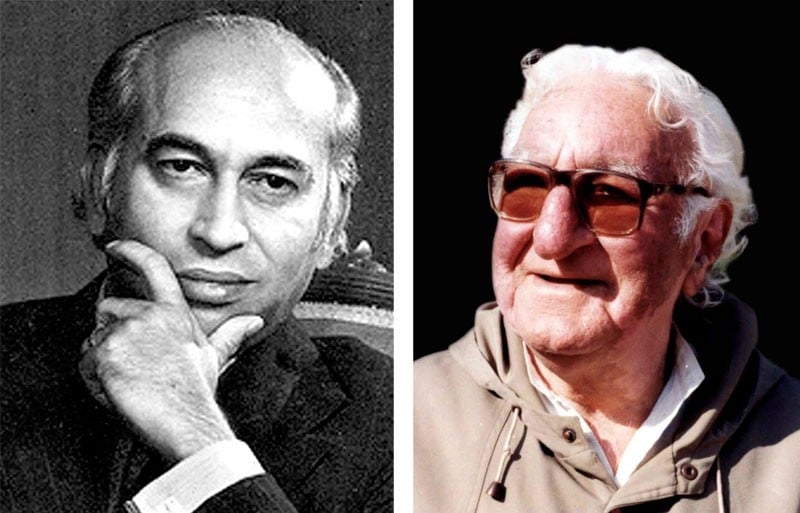

In 2015, students of history may celebrate or mourn the 40th anniversary of the dissolution of NAP that Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto had planned in much advance but carried out in 1975. This dissolution and its approval by the Supreme Court in October 1975 had far-reaching impact on the political developments in the decades to come.

Though normally General Ziaul Haq is blamed for mutilating the constitution, independent observers of history would do better by giving the credit where it is due and have a look at the first seven constitutional amendments brought in by none other than Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. There is no gainsaying the fact that the five military men -- Iskander Mirza, Ayub Khan, Yahya Khan, Ziaul Haq and Pervez Musharraf -- have done more harm to this country than all civilian rulers put together; still it needs to be stressed and highlighted that the civilians -- whenever they could -- were not far behind in this race for MAD (mutually assured destruction).

The First and the Second Amendments to the 1973-Constitution were passed in 1974. Commonly it is believed that the First Amendment recognized Bangladesh and the second declared Ahmedis as non-Muslims. But a closer look shows that both amendments were not as innocuous as they appear to be. Bangladesh had already been recognized as an independent country to ensure Mujibur Rahman’s participation in the Islamic Summit Conference in Lahore in February 1974; by amending Article 1 of the Constitution in April 1974, any mention to East Pakistan was deleted. But there were other aspects of the First Amendment that showed signs of what Bhutto was up to.

More drastic changes were made to Article 17 that paved the way for curtailing the freedom of association; new restrictions were imposed on this freedom to form associations imposed by law in the interest of sovereignty or integrity of Pakistan. Based on this amendment, Political Parties Act 1962 was also revised, empowering the federal government to declare any political party as working against the sovereignty and integrity of Pakistan; the accused party would stand dissolved and all its properties and funds would be forfeited to the federal government. Of course, the Supreme Court could overturn the government’s declaration, but keeping in mind the subservient judiciary it never happened.

Why did Bhutto do it? Apparently, there were two major reasons for that: Bhutto not only wanted to destroy the main opposition party, NAP, but also had a feeling that some disgruntled elements within his party such as Ghulam Mustafa Khar and JA Rahim might decide to form a new political party; so Bhutto wanted to keep the sword in his hands to use when the opportunity arose.

The Second Amendment mainly dealt with the Qadiani issue but had other implications too for Pakistan polity. For the first time in world history, an elected parliament took it upon itself to decide the fate of a religious denomination by passing judgments on the circumference of a creed. A matter that even Justice Munir Report of 1950s had left open for discussion, was now closed and sealed to the merriment of some of the most seasoned politicians in Pakistan. It precipitated the demand for declaring other minority sects as infidels as well. The wheel was set in motion that would ultimately tear asunder the very fabric of this society.

The year 1974 ended with JA Rahim being removed as secretary-general of Pakistan People’s Party and Dr Mubashir Hasan taking his place. The story of JA Rahim being maltreated by Bhutto’s goons is well documented, but even more surprising was the readiness of Dr Mubashir Hasan to take Rahim’s seat rather than voice his concerns. Little did Mubashir realise that soon he would also be on his way out.

The year 1975 saw another two amendments to the Constitution, aimed at strengthening the federal government’s powers to victimise political opponents and curtail courts’ jurisdiction respectively. Though the courts were already meek and mellow, hardly ever disappointing the federal government; Bhutto was becoming increasingly intolerant of opposition’s repeated recourse to judiciary against his highhandedness.

February 1975 was an eventful month; the National Assembly passes the bill for terrorists’ trial by special courts. The situation became clear on February 8 when Hayat Mohammad Khan Sherpao was assassinated in an attack in Peshawar and within a week, NAP led by Abdul Wali Khan was declared illegal and banned. Within a couple of days, the Third Amendment to the Constitution was introduced curtailing the rights of the detainees, and extending the powers of the detaining authority. The safeguards against preventive detention were reduced and the period for preventive detention was extended from one month to three months without production before a review board. Now any person could be detained indefinitely if he was ‘acting or attempting to act in a manner prejudicial to the integrity, security, or defence of Pakistan.’

The Bhutto government also amended the Code of Criminal Procedure and prohibited the courts from granting bail before arrest to a person unless a case was registered against him. Such bails before arrest were a safeguard for political workers to save themselves from victimisation, and a court could approve such bails even if there was no case registered but a victim anticipated that a case would be filed and he would be arrested before approaching the court.

The purpose of the Second and the Third Amendments was now evident; NAP was the main target of both. Wali Khan and almost the entire leadership of NAP was put behind bars and the only major political party that stood for liberal, secular, and progressive ideals was about to be crushed, dealing a severe blow to the prospects of democratic norms in the country.

The same old drama that had previously portrayed Bengalis as traitors was now modified to include new villains supposedly working against the country that the new protagonist i.e. ZA Bhutto was trying to defend. Whereas Bengalis had been accused of playing in the Indian hands, the NAP leaders -- mainly Pakhtun and Baloch -- were projected as Afghan agents.

Wali Khan was a towering personality, son of a great freedom fighter, and had been designated leader of the opposition in the National Assembly. Against Bhutto’s phony Islamic socialism, Wali Khan was arguably the only political leader with better credentials as a democrat whose entire family consisted of stalwarts such as his father, Abdul Ghaffar Khan, brothers Abdul Ghani Khan and Abul Ali Khan and his uncle, Abdul Jabbar Khan (Dr Khan Saheb).