While the state failed to adopt Urdu as the official language, it failed equally in adopting provincial languages for teaching and other official business

The Supreme Court has directed the federal and provincial governments to adopt Urdu as the official language in the country. Announcing the verdict on a petition pertaining to promotion and implementation of Urdu language, the top court has directed the government to fulfill its constitutional obligation.

The court order follows Article 251 (1) of the constitution that reads "the national language of Pakistan is Urdu, and arrangements shall be made for its being used for official and other purposes".

Whereas the verdict reiterated this constitutional provision, it remained completely silent on sub-Article 3 to the same effect that reads "without prejudice to the status of the national language, a provincial assembly may by law prescribe measures for the teaching, promotion and use of a provincial language in addition to the national language."

While the state failed in taking fitting measures to adopt Urdu as the official language, it failed equally in adopting the provincial languages for teaching and other official business in provinces. It would have been more realistic if the court had also directed the provincial governments to fulfill their constitutional obligation towards provincial languages.

In a federation like Pakistan, such gestures of inclusiveness will help cement the bond between the citizens and the state. Apart from its political ramifications, the use of provincial languages for education and other official business would proffer an enabling environment to millions of citizens who do not use Urdu in their everyday life.

According to the census of 1998, Urdu was the mother tongue of only 7.5 per cent of the population even after five decades. Scientific research has established that teaching in the mother language at the primary level forms the bedrock for cognitive abilities. Moreover, communication and official business in provincial languages is a genuine need for a commoner.

Ironically, rather than a uniting element, language was made a divisive factor in Pakistan from day one. A persistent obduracy along with the enforcement of mono-culture in the name of national unity only jeopardised the illusory one-nationhood.

Last year, the National Assembly’s Standing Committee on Law and Justice repudiated a bill, seeking the status of national language for major Pakistani languages. The bill was tabled by PML-N legislator, Marvi Memon. Only a few months ago, the Standing Committee of the National Assembly on Information, Broadcasting, and National Heritage adopted a resolution to declare 13 languages of Pakistan as national languages. Commenting on the bill, Special Secretary of the law ministry, Raza Khan, said that there should be one national language of a nation.

There are numerous examples where more than one languages have been accorded the status of national language. Arabic and Berber are the national languages in Algeria. Finland has two national languages: Finnish and the Swedish language. India has 23 official languages, including Sindhi and Urdu. Nigeria recognises three ‘majority’ or national languages namely, Hausa, Igbo, and Yoruba.

Singapore has four official languages: English, Chinese, Malay and Tamil. South Africa has 11 official languages. Switzerland has four national languages, including German, French, Italian, and Romansh. In Hong Kong, English and Chinese are official languages. In Sri Lanka, Sinhala and Tamil are the official languages.

Read also: Instrumental role

Pakistan is a federation consisting of a mosaic of cultural entities and history. Cementing federating units into a monolithic nation on the basis of religion or a manufactured identity has failed to work so far. Federations can only survive and thrive on the principles of political, cultural, and economic justice.

In Pakistan, the seeds of discontent were sown right from its inception when Bengalis demanded Bangla to be the national language, along with Urdu. The West Pakistani establishment despised Bengali language. They wanted to rule the nascent country through cultural hegemony and, therefore, exalted Urdu as a symbol of Islam and two-nation theory.

It was considered that making any other language as official language will jeopardise the national unity and security. Liaqat Ali Khan and his coterie were the protagonists of this ‘philosophy’. Even Jinnah’s sagacity was clouded by this notion. However, rulers had to succumb to the Bengali language movement and eventually the Bengali language became a national language along with Urdu through Article 214 of the Constitution of 1956.

The same precedent can still be followed to elevate the status of other Pakistani languages. For example, Sindhi remained the official language of Sindh before partition when it was not even a province. Sindh, being the first province to vote for Pakistan, lost its official language in the new country. The sentiments of Sindhis were deeply hurt.

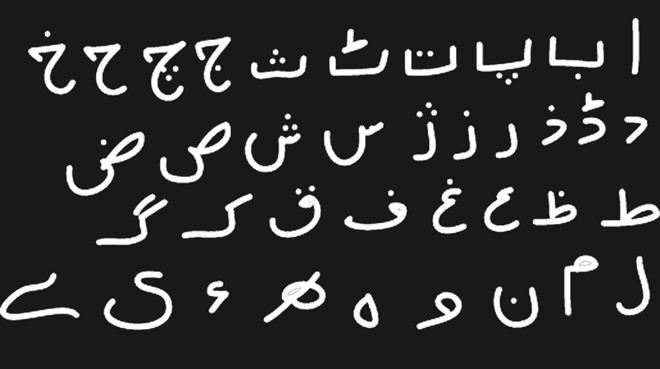

Likewise Punjabi, Seraiki, Pashto, Balochi, Brahvi, Hindko, Shina, Torwali and other languages are part of a cultural treasure trove. Respecting and promoting other Pakistani languages doesn’t demean Urdu by any means. Cultural diversity is misconstrued as a weakness; it is rather a formidable strength of a society.