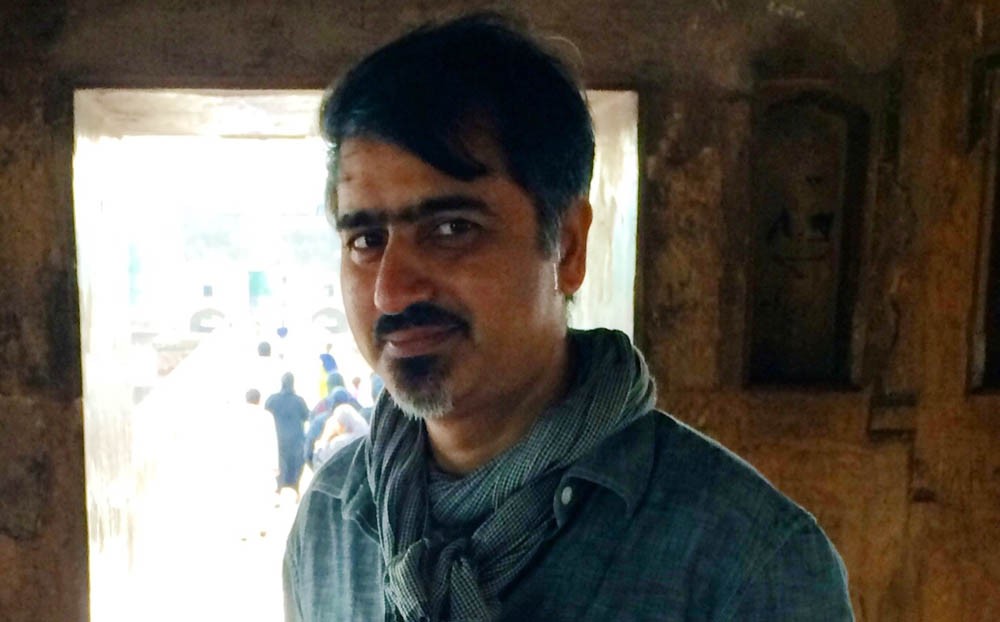

Poet and writer Naveed Alam talks about his love for teaching creative writing

Naveed Alam is a creative writing mentor whose classes become the hub of young enthusiasts. Their admiration for him matches their own keenness to learn, and at times it becomes difficult to separate the two.

Born in Jhelum, Alam left for the United States after high school where he received his MFA in Creative Writing. Since then, he has been teaching creative writing at different platforms, including the City University, New York for over a decade. He has been holding different Creative Writing workshops at various universities in Lahore.

His first collection of poems, A Queen of No Ordinary Realms, won the Spokane Poetry Prize. His works have been published in several literary journals and magazines including the Prairie Schooner, American Poetry Journal, Poetry International, International Poetry Review, Cimmaron Review, and the Canadian Dimension.

These days he’s translating Punjabi poet Madho Lal Hussain and the book is expected to come out in January, 2016. Recently, TNS got a chance to interview him in Lahore and talk to him candidly about his love for teaching creative writing. Excerpts follow:

The News on Sunday: Having stayed in the US for two decades, what brought you back to Pakistan?

Naveed Alam: I came back to Pakistan because of some personal issues and was sceptical that I wouldn’t be able to adjust. What compelled me to stay back were the youth that I met here. They had as much exposure as any student in the US would have. They were different from what we were at their age and I prefer communicating with them. Also for a person like me who is involved in writing, art or literature, moving back was natural. When you re-connect [with your own land], it’s a re-supplying of energy and re-invention of your own thoughts. You realise that actually these were probably some of the missing dots -- literary dots -- from your goals that are coming back.

TNS: While teaching creative writing you have to lay down rules and make outlines. Does that not kill creativity?

NA: For many in Pakistan, the term ‘creative writing’ means: to be creative and allow your creativity to run and get over with it. But in academic terms when we talk about creative writing (from the experience of training where I come from) we are specifically talking about fiction and poetry.

When people enroll for a creative writing class, they all come with the same expectation -- that they would have all the freedom to write in any way they want. The first lesson is that creative writing doesn’t happen in a vacuum. For instance, if you go to a music class and say that I want to play an instrument ‘creatively’, you won’t just pick up the instrument and start playing it by yourself. You need to learn it first. Creativity comes at a later stage, once you’ve mastered the technique.

Same is the case with language; language can’t be learnt without rules and if you don’t know the basic rules, you are like that person who wants to write poetry and has just learnt the alphabets. Once you’ve learnt the rules, feel free to break them, but first demonstrate your ability to master those basic rules.

In creative writing, you don’t need to listen to your teachers in a conventional way but to find your favourite poet or writer and see their techniques and crafts closely and see the long process of their development as writers.

TNS: Why do you think introducing creative writing would be a good idea in Pakistan?

NA: It existed earlier as well, but there was no formal channel for people to produce and to develop that class. In fact, so many students sent me their work independently. So in a way students are the ones who started it. Once the students found a formal setup, their response was overwhelming. As a creative writing mentor, I just want to give the students that environment where they can share, learn and help each other to get to their next process. They might discover that process on their own but as a teacher you want to be part of that process of discovery.

Creative writing can be a process of understanding literature. If you can deconstruct a story and reconstruct it, I think you have a better insight into a story out of that rather than reading the analysis of many different scholars. A creative writer has a better chance to understand any piece of literature than traditional students of English.

TNS: When we think of creative writing, why does English literature come to mind? Why is being creative and writing in English so mutually inclusive?

NA: Not only English but American English [he laughs]. The reason is that creative writing started in an American University. Once it started, people tried to mock it. They said writers are not produced in universities, they are produced in everyday life. Either you have it in you or you don’t; you just can’t learn it.

Even today some of the established writers react strongly to all the creative writing workshops. They are of the opinion that these workshops are not producing any talent but only uniform styles and uniform thinking for individuals.

Creative writing has proliferated; there are more than 300 MFA programs [the world over]. The justification of why [they mean] only English or American English is because their universities have better funding and hence their students have better opportunities. It was natural that Americans, better or worse, were on the cutting edge. It was not just creative writing, but art and music also shifted to New York.

I think some of the best contemporary works of literature are not being written in English. They are being written in other languages and the reason is that America, despite having all those resources, is culturally a much insulated society; their direct exposure to what is happening outside their world is very little. Compared to people who are outside America, they have to know more than their immediate reality in order to survive.

In Pakistan we cannot survive only with Punjabi and Urdu; we have to know English as part of our survival. Through that, we’ll be able to understand reality from multiple perspectives and this multiplicity will enrich our understanding of the world around us. It will lend complexity to our thought process and writing process and to our expression--to the way we articulate things.

TNS: What is the scope of teaching creative writing in Urdu? Will that be equally powerful?

NA: Absolutely, I was thinking along these lines that if I were to offer a workshop I would let people use any language they prefer. My challenge is to get hold of a person who is a writer or a poet in Urdu or Punjabi, who can help me in giving feedback in Urdu. The reason is that my understanding of the Urdu and Punjabi language is not as good because all my formal training has been in another language.

People who are interested in language in order to express and explain themselves, for them words carry a sense of identity; language is a sense of identity. When you are bicultural, one foot in English and one foot in the language you belong to, it is very important to keep the balance between the two especially when you’re dealing with English because it is such a dominant and hegemonic language. Once you engage with it, it can completely erase other aspects of your identity.

And to be able to cope with such complex lingual challenges, you need to struggle in a way that from the conflict situation of these languages you achieve the point where they blend in a harmonious way.

TNS: You have been associated with both poetry and teaching creative writing at many platforms; both considered alien and less appreciated in Pakistan. How do you deal with it?

NA: Pakistani students are open to ideas and accept new academic reformation. Forman Christian College, Beaconhouse National University and LUMS are not typical institutes. I would be much happier if I got a chance to teach creative writing at the Punjab University or at Government College. Now someone will turn around and ask why don’t I do that? And I would say give me the tools and access and I would definitely go. I think if creative writing is taken to an institute where students sit on the taat and learn, they would produce marvels and I would be content if they are given the similar opportunity.