In her recent exhibition at Rohtas 2, Faiza Butt explores a dimension of the present world in which everything turns into a commodity or an exotic item

"To deny the humanity of other people is the very essence of terrorism." -- Simon Leys

The history of past few decades is marked by extraordinary events that altered the world to a great degree -- beginning with the fall of Berlin Wall in 1989 to the attacks on the Twin Towers in 2001.

While the gap in the fall of Berlin Wall and the destruction of the World Trade Center (interestingly, both events that changed the course of history brought down two architectural structures) was of twelve years, after about fourteen years the world is witnessing a new and unprecedented phenomenon. Thousands of refugees fleeing the Syrian cities in particular and the Middle East and North Africa in general are marching into Europe to seek asylum.

The images of these de-situated groups, often walking literally on the map, as they cross territory after territory, do not seem to belong to the 21st century. They remind one of the pilgrimages and crusades of the medieval period, when hordes of soldiers and believers travelled from one kingdom to the neighbouring one. Only they were travelling in the opposite direction -- from Europe towards the holy lands of Middle East.

It is not yet clear how many years it would require for the travellers of our times to attain the status of citizens but it is certain that their presence in the European society will impact its culture. Their migration also reinforces one of the biggest issues of our age, that of religious fundamentalism and extremism. These people from Syria and North Africa are mainly victims of the ISIS; a new form of fanaticism is spreading in the Middle East, especially in regions that were considered the cradles of early human civilization. ISIS, along with its atrocities on humans belonging to other religions, faiths, sects and beliefs, has a hard approach towards the past. It is fighting with history by annihilating the relics of the past -- bombarding historic monuments in areas captured by its forces, most recently in the ancient Syrian city of Palmyra.

While fundamentalists eliminate history, creative individuals try to save it. The works of art are attempts to capture and preserve the present (which constantly and immediately turns into the past) for future generations. Hence literature, architecture, art, music, drama have been a few means to deal with the erosion of history.

The recent exhibition of Faiza Butt’s art held from Sept 9-23, at Rohtas 2, Lahore affirms this aspect. Works executed in different scales and mediums are connected due to the artist’s concerns about her contemporary world. It’s a world where, like globalisation, terror has also become multinational as the two phenomena share a marketing side too. If globalisation manifests itself in the form of profit through brands, food chains and commercial stores situated world over, images of terror and the war waged against it has also had monetary benefits.

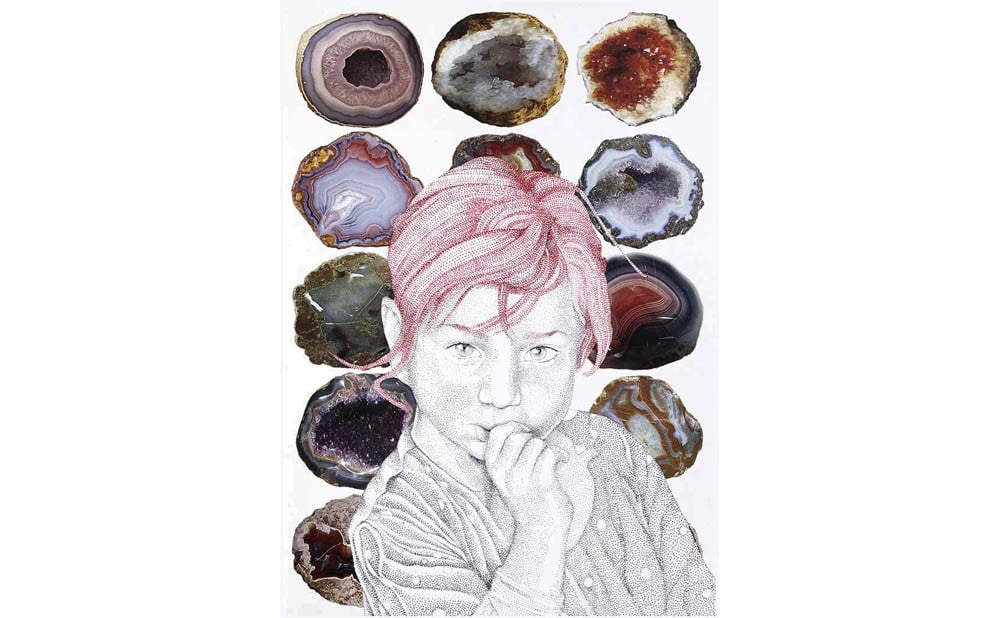

Today, after the demise of the bipolar world and the invalidity of nationhood, it is the international market that is supreme -- in selling jihad as well as other products. Butt addresses these issues in her work by focusing on how human beings are not only surrounded by commercial objects, but are consumed as entities under separate labels. An important part of the exhibition is the works with portraits of men and children with different backgrounds, rendered in her trademark pointillist technique. In five of these (Double, Re-Vision and three from the series Ghost,) colour of the paper is used; whereas four works (Erosion3, 4, 5, 8) include digitally-printed images of precious and semi-precious stones cut in raw state. The last one in this section, Oblivion, is composed of a man with various items crowding his surroundings.

Except the last one, other works operate in a subtle situation of shifting identities. Some faces in these works (of girls with covered heads and a man with turban) presumably belong to Afghanistan or Northern parts of Pakistan but, because of their features, can conveniently be classified as European. In a sense, they are not much different from other figures with blonde hair wearing western outfits in her works.

Faiza Butt has been exploring this dimension of the present world in which everything turns, rather is converted, into a commodity or an exotic item, be that a new gadget or the categorisation of a race/religion. In her work, characters from unknown land that lies somewhere between East and West exist amid items of various origins, usage, value and attraction.

Her exhibition also consists of 10 Duratrans light boxes constructed with texts and images from separate sources. On smaller pieces titles such as Not You, Same Old Story, Star Trek, Star Wars, War of the World and Masters of the Universe are inscribed against a backdrop of luminous nature, including pictures of sliced stones and night sky. Letters, composed in jewellery-like forms, lend decorativeness to these pieces, besides blending words and background imagery. Using the same medium, Butt has created four large panels (The Unsaid, Postcard From Kashmir, My Tattered Shirt and Snowman) in which the upper part has poetry by Agha Shahid Ali or Faiz Ahmed Faiz arranged in a structure derived from popular jewellery pieces and the rest is filled with scenic mountains, clouds and blossoming branches. Two of these also include winged figures of a man-animal creature composed in mirror-like scheme. All of these are superimposed with strokes of black paint or blobs.

The four panels were originally displayed as ‘large split cube’ at the New Art Exchange, Nottingham, UK; and according to the artist: "The cube refers to the aesthetics of Kaba, yet it is adorned with secular poetry of two great poets from Pakistan." One can assess the artist’s desire to build an imaginary realm that refers to the current condition of the world struggling between secularism and religious forces. The winged figures from Assyrian civilisation, the style of writing English letters that reminds of Kufic script, and the unavoidable black marks on beautiful views can be linked to the present political turmoil (particularly connected to Da’esh and its destructions).

Yet it is difficult to arrive at a definite conclusion, as it is hard to read the text of poetry in these pieces as well as find the meaning of the exhibition’s title -- Paracosm.