Only a synthesis of leftist thesis and rightist anti-thesis will yield an analysis anchored in pragmatism

The boundaries are perhaps more blurred today than they were ever before in defining who is a leftist and who subscribes to right in Pakistan. Even mine is not the attempt to define either. In other words, there are people either with rightist or leftist leanings. In the context of Pakistan’s intellectual milieu, there are a few broad characteristics which help us to figure out who symbolises left and who symbolises right when it comes to identifying reasons for the country’s security woes.

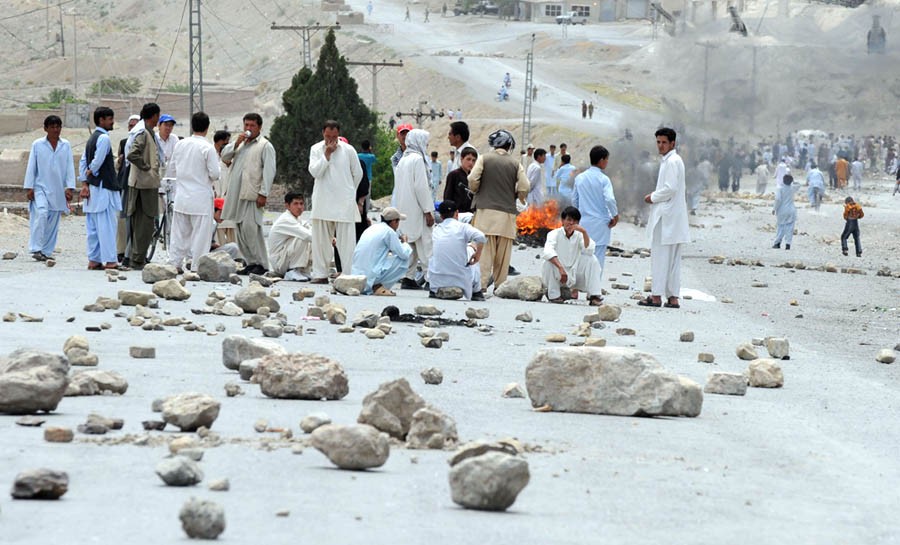

For the right, the outside world causes Pakistan’s multifarious security issues. There is a triangular nexus of countries, which stands for hurting Pakistan. Led by the US, India and Israel are out there to harm Pakistan. Muslims can’t do any harm to fellow Muslims, they rant. From bomb blasts to suicide attacks to shooting innocent humans in the name of religion to bad image abroad, all are attributed to the perceived tripartite nexus, no matter how many times the local sources claim credit for the bestialities or our mismanagement is blamed for.

One who raises questions about the veracity of the unsubstantiated claims made by the right franchise is snubbed: "don’t forget the whole media is controlled by Jews to the detriment of Muslims." The ruling elites are the lackeys of the US and it is insane to expect them to speak the truth, they allege. Rightists will count you several ill-fated Pakistani leaders who fell out of favour with the US. Left has its own peculiarities.

Pakistan’s problems, writers with leftist leanings believe, are the result of its rulers’ imprudent policies. From the rise of Taliban to other non-state actors who are bent on wreaking havoc, flawed policies of the past military and civil governments are responsible for the predicament we find ourselves in. They almost nearly absolve other regional states of any involvement in Pakistan’s internal affairs. To them, the so-called involvement of foreign hands in Pakistan’s domestic affairs is the ploy of the deeply entrenched ruling elites to justify their exploitation based rule over the masses.

The country’s enduring security woes are attributed to the continuity of the wrong policies of the past. The right and left perspectives have both their strengths and weaknesses. The need is to synthesise the combined strength of the two world views and discard their weaknesses.

The strength of leftist analyses is that they tend to induce internal reforms. They lay emphasis upon putting one’s house in order to own responsibility for failures. Contrary to this, expecting the alleged opponent or enemy to change its policy for the betterment of yours is akin to expecting the near impossible. Better to reform from within is rational; sooner the better.

Nevertheless, the main weakness of the leftist scholarship is that it downplays -- sometimes bordering on near denial -- the very essence of international politics: in the pursuit of narrowly conceived national interests, states know no ethics including interference in a country’s domestic affairs. Most of the times, regional countries’ sponsorship to militants of various stripes is considered as a mere canard concocted by ruling class to conceal failures.

Indeed, regional states have been allegedly exploiting Pakistan’s internal vulnerabilities by aligning themselves with Pakistan-based non-state actors. Dhaka debacle back in 1971 is a glaring example of India’s support to Bengali separatists. In fact, foreign involvement takes place through local proxies and hence it becomes too difficult to identify the "invisible hand." Even if a foreign agent is arrested, "plausible deniability" in the form of disowning the individual finds its fullest expression.

The main strength of the right is that it has cognizance of the opponent states meddling -- though in an extremely exaggerated form -- in Pakistan’s internal affairs. Nevertheless, the right’s primary weakness is their conspiratorial base. Hardly one finds any substantial evidence in the case of rightist analyses. A spate of hostile statements from opponent states suffices for their involvement from right’s worldview. Any evidence in a case is accompanied by inflated exaggeration, however.

There is, in other words, an irrational hostility towards USA, India and Israel. If anything untoward happens, the troika is advertently implicated. Thus, whereas leftist intellectual milieu is self-critical and inward looking, its rightist counterpart is xenophobic and outward looking. A synthesis of leftist thesis and rightist anti thesis will yield an analysis anchored in pragmatism.

From a pragmatist perspective, we are primarily to blame ourselves for our myriad security problems. Regional states only exploit the sources of grievances that are purely local. For example, Taliban militancy is the result of decades-long sponsorship to non-state actors by various governments in Pakistan though one cannot overlook the US’s overarching role in arm-twisting Pakistan to do its bidding in ousting former Soviet Union from Afghanistan. The diminishing Baloch separatism, in its fifth phase since 1948, is a domestic concern apparently exploited by India. Similarly, although Pakistan is a cockpit of rivalry between regional states on sectarian front, madaris’ syllabi is the key to understanding the sectarian conflict.

In penultimate analysis, for efforts against militancy of various hues to succeed, Pakistani policy makers seriously need to reform its ill-conceived policies. Ownership of failures is a must first step in the right direction than a mere finger-pointing at others. Until we address the local sources of our security issues, flawed legacies will keep haunting us. Change from above will trigger change at the lowest rung of society.