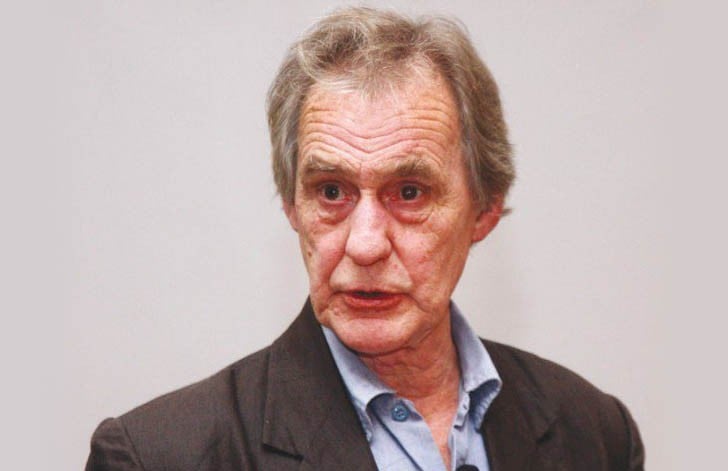

Hailed as "one of our most outstanding historians", John Keay talks about the simplistic historicisation of South Asia, and how he addresses Partition within the larger polemics of society and politics

Born in 1941 in Devon, England, John Keay was educated at Ampleforth College, York and Magdalen College, Oxford, where he was a demy scholar in Modern History. His tutors included the historian A J P Taylor and the playwright Alan Bennet.

After a brief spell as a political correspondent for The Economist in India, he embarked on a career as a full-time history writer zeroing in on South Asia and its richly textured yet complex evolution. The string of acclaimed works by Keay include more than twenty titles, the most recent being Midnight’s Descendants: South Asia from Partition to the present day, and the list of accolades and laurels include Sir Percy Sykes Memorial Medal, and Literary Fellowships at the University of Dundee and at the Royal Conservatoire in Scotland.

Hailed as "one of our most outstanding historians", he talks to TNS about the simplistic historicisation of South Asia, and about how he addresses Partition within the larger polemics of society and politics.

The News on Sunday: How did you get interested in South Asia as a focal area of interest, research and study?

John Keay: Unlike a lot of British people, I didn’t have any family connection with the British Rule in India except a very distant cousin in the Nagalands. He wasn’t very sympathetic towards India, anyway. I just happened to come to Kashmir in 1965 for a short fishing holiday. (My sister who used to work for British Overseas Airways -- what has now become British Airways accompanied me). If she came along too, I could travel ten per cent to the full fare as a brother or a companion, so it was an attractive idea to come to Kashmir. I had heard about the trout from Scotland being hatched and reared in Kashmir.

About a year later, I came back and actually lived in Kashmir for about six months on the outskirts of Srinagar. It was there that I started writing freelance journalism because I needed to earn a bit of money to pay for my accommodation, and sending it to anyone who would publish it. I established a relationship with The Economist as a political commentator writing political pieces on the situation in Kashmir in the 1960s. As a result of that, when I came back to the UK, The Economist started sending me as a special correspondent to India (for the elections) or to Pakistan (during the war in 1971) and so forth. So I had a short stint as a political correspondent, and extended my knowledge of South Asia from Kashmir to India to Pakistan to what became Bangladesh.

Soon after that I wrote my first book Into India which is a simple introduction to India, published in 1973. After that, I wrote two books When Men and Mountains Meet and The Gilgit Game on the exploration of the Western Himalayas. (They were meant to be one book but became two, published circa 1979).

TNS: What has been your approach to writing history?

JK: Apart from a stint in the 1980s, I made quite a few programmes here and in India, Nepal and Bhutan, for BBC Radio 3, which is kind of an upmarket channel -- intellectual and always interested in new ideas. These were very political programmes about all aspects of the arts, culture, history, and to some extent, economics. (I’ve made a few more radio programmes since in the 1990s, but I’ve been mostly writing books. I’ve written about twenty books, and suppose half of them are on South Asia. The other half are about other parts of Asia: I’ve written a big history of China, histories of Southeast Asia and West Asia, and that of the Middle East; and also of Indonesia. In addition, I’ve written a couple of books about Scotland and edited two big encyclopaedias: The Collins Encyclopaedia of Scotland, and The London Encyclopaedia which has been around for a long time).

The other field I’ve written quite a bit in is the field of exploration. I wrote The Royal Geographical Society’s History of World Exploration, and one or two other studies of mostly early-nineteenth century exploration. I don’t like to be described as an historian, and much rather prefer to be called a history writer because I don’t teach history and am not attached to any historical faculty at a university. Most of the history writers we revere most in England like Gibbon, Carlyle, Macaulay, may be even Churchill, weren’t actually historians in the sense we understand it today. They were men of ideas with broad horizons. That’s the sort of history I hope I am trying to write rather than the narrow focus of academic history where you have to specialise, to a large extent, in a particular period or country or theme.

TNS: What, in your opinion, characterises South Asia as a distinct region that sets it apart from any other part of the globe?

JK: To me, South Asia had always had an enormous appeal because of its people. It obviously helps a lot that people speak English here, which makes it much easier to communicate and form friendships than it is in China, for instance, where relatively fewer people can speak English. Basically, I’ve always found South Asia much more sympathetic; I find people here much more endearing, more interested, more charming (it sounds a bit superficial though) and accessible than certainly China or the Arab world. Be it politicians, writers or artists, they are much more approachable here than in most other countries. India is a nice place to work if you are dependent on interviews, whether it’s for a book or a radio programme.

Also, in terms of history, I find it to be much more relevant here than it is in Europe. I studied history at Oxford and was totally bored because it was all about constitutional documents and dynasties -- there was nothing new to say about them.

History doesn’t cause any excitement in the UK or in most parts of Europe because it’s not relevant to today’s events. People are much more excited by history and are historically conscious here, sometimes in an unfortunate way.

Initially I fell in love with Indian and South Asian architecture -- monuments, ruins, castles, forts, and palaces. I guess these places appeal to you if you have a slightly romantic bent of mind. I wanted to know more about the origins of these buildings -- whether they were religious or secular buildings. I was impressed by their settings too -- the hidden archaeological sites, which may not look exciting to most people, fascinated me. The excitement about antiquities was also a contributing factor to my passion for this part of the world. China, for instance, doesn’t have anything like what my cousin calls the "greatest galaxy of monuments" in the world while referring to British India.

TNS: How do you see the shifting socio-political and socio-cultural landscape of South Asia today with the rise of Hindutva and the Saffronists?

JK: This is a vital question particularly for India. On the other hand, I think this distinction between secular India and Islamic Pakistan or Bangladesh has been slightly exaggerated. To me Indian secularism never meant secularism in the sense we understand it in the West, of encouraging a kind of atheism. Secularism in India has always just meant that no particular place or religious group is discriminated against in any way. But, in fact, there have not just been religious groups in India but also that India has had the most appalling record of caste discrimination, and so on.

The difference between an Islamic society and a secular one has been exaggerated, and there’ve been just as many casualties from sectarian hostility in secular India as there have been in Islamic Pakistan. People often say that India is a democracy whereas Pakistan and Bangladesh are inclined to favour all kinds of military governments. But actually, more lives have been lost in elections than in military coups. India is by no means without a strong authoritarian streak in government, even today.

In terms of the BJP, I am really no authority on it after Modi came into power about a year ago. So it’s hard to judge, although there have been BJP governments in India before, usually either as part of a coalition or as a major partner. They behaved quite responsibly. I mean Vajpayee’s government in the late 1990s was probably responsible for making more progress on the Kashmir issue in trying to normalise relationship over Kashmir with Pakistan than a succession of Congress governments. I don’t mean to ignore the fact that India has a BJP government but the raw elements within the BJP who are alarmingly intolerant, the conception of Hindutva, the underlying idea that all Indians are basically Hindus is just very threatening, not just to Muslims but also to Christians, and to people of other faiths in India too.

Sometimes, the extremist governments of the Right or of the Left can actually behave much more responsibly in pardon, and their power is actually quite good for them in toning down discrimination in the party mould if they are in opposition.

TNS: You must have read the modern Indian historian, from Percival Spear to Romilla Thapar to Rajmohan Gandhi. What is your take on the version of history approached or written by the Indian historian? Do you see any bias there?

JK: History does have some prejudice whatever the situation. Among the Indian historians, Ramachandra Guha is a good friend. Irfan Habib, I may have met once or twice. (There’s always a tendency to complain that the only internationally respected Indian historians are all Marxists. Romilla was also and probably still is proud to call herself a Marxist, from time to time. I bet it’s become a pejorative, and their work is marred by its association with Marxism).

Another historian whom I much admire is Damodar Dharmananda Kosambhi -- a Brahmin historian and a very famous mathematician. He started writing about history while being opposed to history. He’s not a Marxist but his approach is really interesting. He thought that Indian historians were too anxious about the lack of documentation in Indian history. Prior to the Muslim invasion, there were very few written documents. He thought it didn’t really matter because one could learn so much by simply observing the countryside, studying local landholding patterns, local cults and traditions, and any inscriptions on architectural monuments. History of India can be pieced together from the ground rather than documented. Kosambhi wrote a couple of wonderful books based on this kind of historical research that has always seemed to me very valid not just in India but also in other countries.

There was also a sub-altern school of history, not so long ago. I don’t know what happened to all the sub-altern historians who thought that a lot could be learnt from studying figures who were not necessarily well-known, high profile political figures, by studying individuals (in the absence of documentation) who had served at a lower level in the government or in the military, and so forth, which is presumably why they were called ‘sub-altern’. They were very popular in the 1980s but less so now.

I think Guha’s India after Gandhi (now he’s working on Nehru’s biography) set a new standard in Indian history writing. He’s a slightly controversial figure but in the same way as Thapar and Habib. He’s certainly not a Marxist, and as far as I know, has no particular affiliation with any group of intellectuals or religiously minded people. He’s a very secular person. Indian history, in so far as I know, has stabilised. (My history of India was written in the late 1990s, and I haven’t been immersed in contemporary Indian history for fifteen years, so I may be a little out of touch). There is actually some very good work being done but how would this be affected by the funding and encouragement offered by the current government doesn’t sound too good. It might want a Hindutva version of Indian history to be penned down by a historian who is willing to write it.

In a way this controversy is good: I like it when people tell me in an abusive tone on the Internet that you are obviously a Hindu basher because you espouse the Aryan series of migrations into India, or that you don’t credit the Indus Valley civilisation to the Sanskriti people. It’s only in South Asia that people take ancient and even uncertain history so seriously.

TNS: Lord Mountbatten played a dubious role in mapping India, leading to its geophysical Partition. Why do you think he was justified in hastening the process?

JK: Mountbatten just wanted to get out. His brief from Clement Attlee when he came out as Viceroy in March 1947 was to wind up the British involvement in India as rapidly as possible. He also had personal reasons for not wanting to stay in India for very long: his nephew was about to marry the future Queen of England who had all sorts of political connections; his own background was in the Navy and the Armed Forces and he had ambitions in that direction. As a Viceroy, he agreed to hold the office on his own terms that he could make whatever settlement he would want. He had total responsibility.

It was after the Calcutta Riots in 1946 when there was a terrible death toll in Hindu-Muslim fighting, when the Muslim League called a Direct Action Day. The British reacted in panic because they thought civil war might break out all over northern India unless they got out quickly. Mountbatten, for personal and for political reasons, decided to rush the whole business; he brought forward the cut-off date for the transfer of power from 1948 to August 1947 which left him with just ten weeks to organise it. And the only way of getting any chance of support of the League and the Congress was by pushing through the process of Partition.

Obviously, M.A. Jinnah had been asking for Pakistan for some time while Nehru had a one-point agenda and Gandhi was totally opposed to any Partition, whatsoever. Mountbatten persuaded Nehru by offering to pull all the princely states into a union with India. Although, by territory and population, the amount India lost by the creation of Pakistan was almost entirely offset by the amount of territory and population required by getting these princely states to agree to amalgamation within India.

It wasn’t quite clear if Jinnah wanted a totally sovereign Pakistan. There was a kind of negotiation and it appeared that he might be willing to accept the idea of Pakistan within an Indian Union, in terms of a mutual treaty. It was also to avoid the partitioning of Bengal and Punjab, as soon as the idea of Partition was promoted by Mountbatten and accepted by Nehru. (Jinnah was told that you could have Pakistan only if Bengal and Punjab were partitioned). Had Pakistan been constituted to include the whole of Punjab and Bengal, and then there would have been the possibility of a joint capital because Pakistan would have lapped against the territory of Delhi.

As I said Mountbatten was so keen to get out that he brought the date forward, and there was so much negotiation involved in terms of partition that no one really thought very seriously about what its implications might be. In Scotland where I live, we had a vote on partition, a referendum on partition from the United Kingdom last September but we had two years of debate before the actual referendum. And the debate hinged on what it would be like outside the UK. There was no debate like that in India. There was no time, so very little talk was given to what would happen after Partition. I think, for that, all the leaders are responsible. They didn’t have the time to work out the implications of what this would involve, so we had terrible migrations and massacres and the greatest movement of human population.

TNS: What makes your last book to date Midnight’s Descendants such a compelling read?

JK: I was about six years old at the time of Partition. I vaguely remember seeing scenes of it on the passé newsreel they used to have in cinemas in those days. So I have no personal recollection of Partition itself. But I have been coming to South Asia almost every year since about 1965. This book is partly informed by personal experience, and is obviously not as faithfully documented as a history of a more remote time would be. When you are dealing with recent history, a lot of documentation is embargoed and is not available to the public. The sort of established preconceptions about things don’t exist here; a lot of events are not entirely clear.

A book like this would certainly be superseded but I wanted to write it because I thought it’s the sort of book that would be very difficult for an Indian or a Pakistani to write because it’s so difficult for you to travel to India, and to speak to people, and to assess the situation dispassionately. It’s the same for an Indian coming to Pakistan or indeed Bangladesh.

In a way, that was my justification as an outsider for writing it. I thought, perhaps, it would be of interest to readers in India and Pakistan to see what I made of the relationship, particularly, between the two, and also with the rest of South Asia. And to remind, particularly the younger generation, how both countries have been so molded by Partition, which they weren’t around to witness.

Old histories of South Asia previous to Partition obviously tended to make no distinction between Pakistan and India. Come Partition, suddenly you get histories of India that don’t include Pakistan, and vice versa. I thought it would be quite useful to have a work that continued the earlier tradition of regarding the Subcontinent as a whole and as a single political entity.