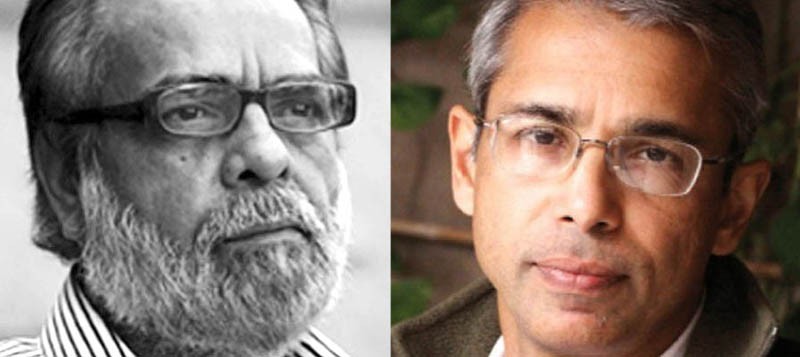

In translating Afzal Ahmed Syed’s poems into English, Musharraf Ali Farooqi has remained as close as possible to the original without being literal

Witness to two wars in his early twenties -- first the 1971 war in which the former East Pakistan became Bangladesh, and then the Lebanese Civil War, as a student at the American University in Beirut -- Afzal Ahmed Syed’s experience of war, brutality and injustice colour his poetry. His work reflects the Sisyphean condition of humankind, most emphatically the circumstances of those born with neither freedom nor wealth, nor the comforts and facilities which citizens of settled nations know.

Syed identifies with the East European poets whose work he has often translated into Urdu, and not perhaps without intention; they are birds of a feather, poets of survival. Perhaps, too, his familiarity with the natural world during his career as an entomologist has also shaped his idea of survival, for humans as for insects.

Having heard Syed read from his work at the Karachi Literature Festival in 2014, I was excited to read his poems translated by novelist and translator Musharraf Ali Farooqi, who is well-known for his prose translation of the Dastaan e Amir Hamza. Intrigued by Syed’s work since his youth, he began translating his poems several years ago; these were published by the Wesleyan University Press in 2010 and have now been reprinted by India’s Yoda Press (another instance of how Indian publishers, rather than local ones, pick up Pakistani writing). My first question here, as someone who did not grow up speaking Urdu at home, and in view of the fact that the younger generation isn’t fluent in the latter, was why this was not a bilingual edition? However, this is a secondary issue, and I have been informed that this will be forthcoming.

For the moment, then, I read the poems in translation, venturing to read only parts of some poems in Urdu, to compare the original with the translated version. Translation is a tricky business, and even the best efforts are often roundly criticised. To my mind, Farooqi has remained as close as possible to the former without being literal. The lines ‘flow’ and the translator has skilfully captured the mood, which is particularly visible where the verse is lyrical. This is important to me, as translations can sometimes be stiff and stilted. There are occasional switches between tenses which might sound foreign to native English speakers, but overall this is a translation in which the reader can be assured that he will enjoy the poems.

One reads the collection beginning with the most recent poems of Rococo and Other Worlds, in which a reader familiar with Pakistan, more specifically Karachi, will immediately be able to place the work. Once I understood the arrangement of the book, however, I moved backwards to the third section containing his first collection, An Arrogated Past. These, his earliest poems, swing between a terrible sense of irony at man’s condition, and the poet’s consciousness of love, and set the tone for the other two collections in this volume, A Death Sentence in Two Languages and Rococo and Other Worlds. ‘An Arrogated Past,’ the poem which gives its name to the first collection, is about survival under conditions which seem to negate the very idea of survival, ‘We survived the massacre/And are now trying/to outwit the targeted killings….Perhaps the theory/that we have evolved double resistance will gain/currency…’ and ‘Death and other privileges/are paid out in our wages….Wrapped in a proclamation/we were stuffed into the barrel of our murderers’ gun/…it was discovered/that we had no ingredient called life/in fact, we had no ingredient/that we did not exist…’

Love appears in short poems as well as the extended prose poem ‘Naujaubna’, one of several fables in the book, in which the narrator sets out with Naujaubna, his soul mate who leads him through the trials of life; his sword, which is not made for pillage but to protect her; and truth. It reads like the quest of man for love and meaning through a life whose circumstances are at once absurd and fantastic. In this collection, too, Syed realises the role of the poet, ‘A poet’s heart is a hound/And the heart of a chained man is a chained dog…’

At the risk of falling prey to the tendency to analyse, -- and according to Syed "a piece of poetry can be transcendent and may appear to have a life of its own. Dissecting a poem robs it of its inherent beauty and converts it into an academic endeavor…’ -- his poetry is an alternate world into which the discerning reader must enter to lose himself, navigating with his intuition, suddenly chancing upon the line, or lines which unlock the poem. This does not always happen with one reading. And while the poet uses simple words, the meaning behind them -- terse or mellifluously lyrical, depending upon the theme of the poem -- is richly complex.

In these very modern nazms, reality is stranger than the absurd; questing knights and heroines resemble characters from myth and fable, traversing the labyrinth of life; and the poet uses references from Western as well as Eastern classical traditions. In a series of portrait poems from Rococo and Other Worlds, Greek nymphs and goddesses appear in the guise of modern women, such as the bank teller Pragat Agarwal in ‘An Impossible Girl,’ with her ‘boatlike eyes’ and ‘musical throat…/In Babylon/she could have been summoned in Aphrodite’s name/and in Carthage/tinkled bells/to attract passers-by into the baths.’

This latest collection contains poems which celebrate and lament Karachi, the city which has been his home since the 1980s, living through its ethnic, sectarian and economic conflicts. But even in these most political poems, the poet’s vision is complete, taking his readers on a journey beyond time and place, holding life up to be examined, as expressed in ‘The Hostess’ (from the second section of the book, A Death Sentence in Two Languages) ‘You bring me the apple…/…and the blood-stained pomegranate/and a poem/and a knife/that cuts things askew.’

This is the manner in which Syed examines history or the here and now, assembling and juxtaposing the ordinary and the decorative with cruelty and the macabre. To round off this review, and to give readers an idea of the poems in Rococo and Other Worlds, I include the first poem of the latter collection.