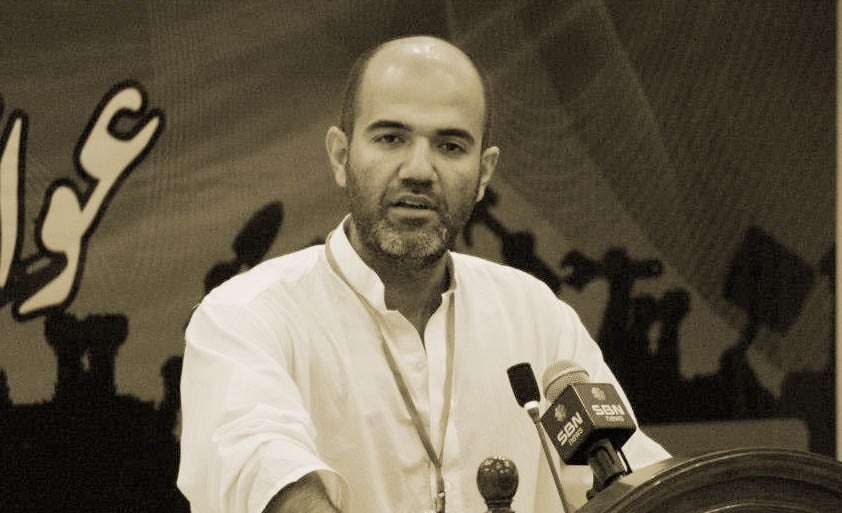

Activist and academic Aasim Sajjad Akhtar criticises the government for its high-handedness in dealing with the Afghan Basti in Islamabad

The News on Sunday (TNS): You have been associated with the issue of katchi abadis and the setting up of Alliance for Kachi Abadis for a long time. How far have you been able to politicise the issue from the platform of Awami Workers Party and what would you consider as your successes and failures in the Afghan Basti for example?

Aasim Sajjad Akhtar (ASA): The Kachi Abadi Alliance was set up as a non-partisan political organisation representing squatters across the country soon after the Musharraf coup in 1999. At that time, it was katchi abadis on Railway lands that were facing the wrath of the state, primarily on the whims of the then Railways Minister and ex-DG ISI, General Javed Ashraf Qazi. We mobilised in many cities and small towns, and succeeded in warding off many evictions, although not all.

Ultimately, the success of such a movement is dependent on the mobilisation not only of katchi abadi dwellers but also the wider society, and particularly democratic forces. Back then, too, we faced a plethora of intellectuals, media-persons, mainstream politicians, and bureaucrats who willfully ignored the complex political economy of squatter settlements and harped on about the ‘illegality’ of katchi abadi dwellers, while propagating the myth that these settlements are hotbeds of crime.

Those early experiences, alongwith subsequent confrontations, and the fact that many of the katchi abadi dwellers with whom we worked maintained links with patronage-disbursing mainstream politicians, clarified that we needed an explicit political vehicle of our own that not only continued to resist evictions but also gave katchi abadi dwellers -- and other segments of the working class -- a political platform of their own. Through the 1960s and 1970s, the urban and rural poor did perceive their class interests to be represented in the political mainstream, but the Zia dictatorship saw the retreat of such politics. The AWP is an attempt to revive the best traditions of working-class politics whilst being responsive to existing objective conditions.

I would say that the AWP and the Kachi Abadi Alliance have succeeded in making this an issue that everyone is talking about. Of course, the state and chattering classes still dominate the airwaves and so-called ‘public opinion’. And this is why the katchi abadi in I-11 could not be saved in spite of the fact that police brutality unfolded on live television in front of the entire country. But I noted above that we have always had setbacks. It is in the nature of what we do, and an overall political environment that can only be called reactionary. We will lose more political battles in the future, too. But the class war continues. And we will continue to fight it.

TNS: What stops the mainstream parties from taking up this issue as their own? We did hear a few opposition parties raising voices within the parliament but only after the bulldozers had done their work. Do you think a political mainstreaming of the issue is what is required?

ASA: I have pointed out above that the political mainstream is generally unconcerned with understanding class issues, let alone taking them on. Mainstream parties are quite content to look at katchi abadis as sources of votes, and, relatedly, sites of mobilisation for rallies and jalsas. In certain cases, therefore, these parties disburse patronage for minor developmental works and/or intervene when katchi abadi residents face victimisation by the local state (thana/katcheri/patwari). But even in these cases, the engagement is highly instrumental.

Over the past 15-16 years I have not gotten the sense that any mainstream party has even a remote interest in long-term planning issues, in thinking about the katchi abadi phenomenon in a deeper manner. Yes, they take up the issue when it comes into the limelight as it just has due to the I-11 case, but as your question suggests, it scarcely makes a difference to those whose homes have already been bulldozed.

So, there is definitely a need for this issue -- like many other class issues -- to be mainstreamed. But we should be under no illusion that the mainstream parties will take up this task. This is why a political party of working people is necessary. It has been more than two decades since the end of the Cold War and a critical mass of young people is slowly coming together around the idea that we need to revitalise the political left. Movements, such as the one to stop evictions in Islamabad, are all part of that process.

TNS: How do you look at the action on Afghan Basti, legally and morally?

ASA: It was under the cover of ‘rule of law’ that the Islamabad High Court, CDA and police first demonised I-11, and then went ahead and razed it to the ground, making more than 15,000 people homeless and then adding insult to injury by arresting dozens and filing trumped up cases under the Anti-Terrorist Act (ATA) against a laughable 2,000 people. In other words, if those in positions of power simply go on about taking land back from ‘illegal’ katchi abadi residents enough, everyone just nods their heads in approval and watches the drama unfold. I should also point out that the authorities also played up the ‘illegality’ of I-11 by beating the Trojan Horse of ‘alien’ Afghans living there -- hence the name ‘Afghan Basti’. But this was a lie, like so many others that were employed to give the whole exercise ‘legal’ cover.

In fact, there are plenty of legal provisions -- both in the constitution and in the form of policy documents -- that protect katchi abadi dwellers from precisely this kind of brutal eviction. These legal provisions were willfully put to one side by the IHC, CDA and Islamabad Capital Territory (ICT) administration. But then again we should not be surprised. The law in this country -- since colonial times -- has always been applied selectively against the toiling classes and in favour of the privileged and powerful.

The last test of just how ‘impartial’ the law and those implementing it are will be in the Supreme Court -- we filed a petition before the operation started, asking for the SC’s immediate intervention. It was not heard in time to save I-11, and we will have to wait and see how the highest court in the land reconciles the way in which 15,000 people were thrown onto the street with the fact that basic rights -- including that to life and shelter -- are enshrined in our constitution.

TNS: With reference to katchi abadis, it sometimes becomes difficult to distinguish between the genuine working class encroaching on a land in the absence of any place to live and the land mafia exploiting their situation. What, in your view, is the ideal way to deal with this complex issue?

ASA: I have already pointed out that the political economy of katchi abadis demands serious interrogation, but our bureaucracy, intelligentsia, and mainstream political parties are simply not interested in initiating this discussion. I don’t see why it is difficult to distinguish between those who live in katchi abadis and those who profit from them.

The state has not bothered to develop formal markets for low-income housing, so an informal market comes into existence to meet poor people’s demand for housing. So, for example, working-class families migrate to an urban centre in search of work; they get word from other workers that some middlemen with links to the CDA are taking money to settle families in a katchi abadi; they seek out this middleman, pay him the going rate, and then start setting up their home in the said settlement. Over the years, they slowly invest in their homes, while continuing to pay the ‘monthly’ to the middleman -- sometimes CDA encroachment crews directly enter the katchi abadi and take additional payments. Meanwhile, electricity and other connections are also acquired through informal means.

The problem is not that there are ‘land mafias’ in operation but that the formal state continuously reneges on its basic responsibility to provide formal housing options. The lack of political will can at least partially be explained by the fact that individual state functionaries that are part of the nexus would much rather prefer to keep pocketing their ‘monthly’ than actually formalising the settlement and having people’s money deposited into the public exchequer. More generally, no one in the corridors of power is bothered with developing the formal housing market, even though it is plainly obvious that the urban poor would pay out of their own pocket to secure permanent shelter.

Also read: A questionable existence of katchi abadis in Islamabad

TNS: The HRCP has taken a cautious note of what happened in Afghan Basti and has talked about resettling of the displaced workers. What do you think of the larger issue of housing for poor people and what are the ways in which the katchi abadis issue can be settled. What about the Housing Policy 2001 and its section on katchi abadis?

ASA: I thought the HRCP’s statement was disappointing -- it was almost apologetic. This confirms the limitations of human rights discourse, just as it makes clear just how reactionary a period we are living in -- many people simply don’t feel they can unconditionally support the struggle of the poorest segments of society because the latter are, after all, ‘illegal encroachers’.

Indeed, so much time and effort has been made to criminalise both the residents of I-11 and those who have struggled with them that our principled and quite reasonable invocations of the law are simply not acknowledged. The 2001 Policy that you ask about explicitly outlaws summary evictions without resettlement, but these and other safeguards were simply put to one side while the state’s propaganda machine did its work.

As for the larger issue of low-income housing, I have already noted how low down on the bureaucracy’s and mainstream politicians’ priority list the urban poor’s shelter needs are. To reiterate, only when the phenomenon is acknowledged for what it is can there be hope that it will be addressed through long-term planning. Right now we are still trying to cope with the state’s repressive arm -- it would be naïve to think that departments like the CDA and legislators will soon make serious efforts to address the actual issue of housing.

TNS: Tell us a little more about what kind of work is the Awami Workers Party engaged with in the katchi abadis.

ASA: We are a fledgling left-wing party, mobilising working-class communities who face the wrath of the state and propertied classes on a daily basis. While most of our emphasis is on resisting evictions, we also confront a plethora of other basic issues confronting residents of katchi abadis, such as disenfranchisement by state agencies like NADRA (which refuses to issue ID cards to many katchi abadi residents; sometimes it blocks cards already issued). Then there is thana/katcheri; the fact of no basic amenities for residents of abadis, and so on.

Some abadis are obviously in much better shape because they have been granted some kind of formal recognition by the CDA and, therefore, do not have the sword of eviction constantly hanging over their heads. But even in these settlements a ghetto culture of sorts has been institutionalised -- the police cultivates touts, reinforces their isolation and generally the institutions of the state and surrounding upper-middle class neighbourhoods sustain the class divide.

The Left is duty-bound to challenge this entire system of exclusion and exploitation, and that is what the party tries to do with whatever resources it has at its disposal.

Related article: A basti that is no more

TNS: Can you give us a sense of the rest of the katchi abadis in Islamabad? Are they safe from any further action by the CDA? The National Action Plan and the perception that these abadis are dens of criminals should be a cause of worry?

ASA: I just noted that some abadis -- 10 in the CDA’s record -- have been declared ‘legal’, and have been regularised in some measure. Most of these are in the F and G sectors and are Christian-majority settlements whose residents work as CDA employees as well as in the homes and private offices of the city’s well-to-do population.

Then there is a list of so-called ‘illegal’ katchi abadis in which up to 42 settlements are named. I-11 was the first big target on this list, but the CDA and the Interior Minister have repeatedly stated that they plan to raze every abadi on that list. The one-member bench of the IHC was, of course, the mover behind this plan, and until and unless there is some relief provided by the apex court, I don’t see the authorities’ intentions changing.

In the immediate aftermath of the I-11 operation we expected more demolitions but the CDA appears to have halted the eviction drive temporarily, perhaps to avoid negative press, and because everyone knows that the Supreme Court will eventually take up the matter. The authorities are likely waiting to see what the SC says before proceeding further, or at least undertaking another high-profile eviction (they are still taking down isolated structures here and there on a daily basis).

As for the National Action Plan and the fact that the propaganda against katchi abadi residents is still ongoing, it is worth bearing in mind that when working people come together to struggle against power and privilege, repression and demonisation are almost to be taken for granted. Even if the katchi abadi residents of Islamabad and those who support them retreat completely, say and do nothing to resist and hand over to the CDA all the land that the latter wants, the propaganda will not stop because the working poor will always remain a ‘threat’ to the rich and powerful. We have to continue doing what we do in spite of all of this, and sooner or later the tables will turn.

The interview was conducted via email.