Abdul Kalam’s life and work should be seen in the mirror at least two other Muslim presidents of India have left their reflections -- Dr Zakir Husain and Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed

With the death of APJ Abdul Kalam, the 11th president of India, on July 27, a long chapter of Indian space and missile technology has come to an end. It is amazing that a person of his caliber spent most of life developing and perfecting weapons that could cause destruction in the range of thousands of kilometers.

Almost all missiles developed by India -- from Agni and Trishul to Prithvi and Akash -- have an indelible mark of Abdul Kalam; and that’s where his image is tarnished in the eyes of peace-loving people, and in the minds of those who work for arms reduction around the world generally, and in South Asia particularly. A man who devotes his life to devices of destruction is usually hailed by his establishment as a benefactor of their nation. Though such ‘benefactors’ might have done some beneficial work too such as a couple of schools and hospitals set up by Dr AQ Khan in Pakistan, their overall contribution to humanity remains negative.

Usually, states have an inherent desire to have monopoly over violence. And in their quest to extend this monopoly across borders, they propagate a false sense of patriotism among their people; a patriotism that is less aimed at enhancing their ability to construct, and more centered at the capacity to destroy real or imaginary enemies. It has to be understood by the people that air-borne weapons -- no matter how sugarcoated they are -- essentially remain a tool of destruction and a potential cause of annihilation of peaceful cities and innocent people; and no patriotic fervour can make such weapons less destructive.

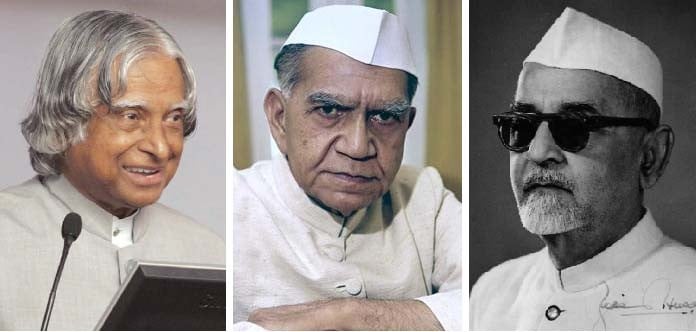

Though Abdul Kalam’s death was mourned across India and he was given a state funeral that he deserved as one of the icons of Indian achievements in air and space, his life and work should be seen in the mirror where at least two other Muslim presidents of India have left their reflections -- Dr Zakir Husain (1897-1969) and Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed (1905-1977). The list also includes Justice Mohammed Hidayatullah, who was acting president when Dr Zakir Husain died in office in 1969.

If we compare the Muslim presidents of India, arguably Dr Zakir Husain stands out as the most towering personalities of them all. In 1920, he became one of the founders -- along with Maulana Muhammad Ali and Hakim Ajmal Khan -- of what later developed as a great centre of learning in India i.e. Jamia Millia Islamia (National Islamic University). He was just 23 years old at that time and was a student at the MAO College Aligarh (later Aligarh Muslim University) that was considered by the Indian National Congress (INC) as pro-British, because it received funding from the British government.

At the behest of Gandhi and other senior Congress leaders, Zakir Husain left the MAO College and established in Aligarh a new college that was later shifted to Delhi with Maulana Muhammad Ali as its first vice-chancellor and Hakim Ajmal as the first chancellor. Husain completed his PhD in economics in Germany at the age of 29 and in 1926 came back to become Jamia’s vice chancellor, a position he occupied for more than two decades.

During this period he also presided over a National Committee on Basic Education established by Gandhi at the advice of Maulana Abul Kalam Azad who was to later become the first education minister of India. After independence, Aligarh Muslim University faced tremendous problems, because most Muslim teachers who were supporters of Pakistan migrated, and the university was seen as a stronghold of the Muslim League, opposed to the INC. Some elements in Congress saw Aligarh University as a hotbed of pro-Pakistan sentiments and a threat to secular India.

That was the time when Dr Zakir Husain was asked by the union education minister, Maulana Azad, to take over Aligarh University so that it could be saved as a national institution. Dr Zakir Husain remained vice chancellor of Aligarh University from 1948 to 1956; then in 1957 Nehru appointed him the governor of Bihar, where he remained till 1962.

In Bihar when the state government tried to curtail the independence of universities through a bill in the legislative assembly, he threatened to resign rather than sign an act that was to be a blow to intellectual freedom of universities. The state government had to backtrack, and no such law saw the light of the day. Now contrast this with the federal and provincial governments’ attempts in Pakistan to minimise the space for free discussion and to terrorise educational institutions so that they follow the official line.

In 1962, when vice-president Dr Radhakrishnan was elected as the second president of India -- after the completion of Dr Rajendra Prasad’s second term as the first president of India -- Dr Zakir Husain was elected the vice-president and ex-officio chairman of the upper house i.e. Rajya Sabha. By 1967, India had seen wars with China (1962) and with Pakistan (1965); her first prime minister JL Nehru had died; the new PM Shastry had been all but forced to sign a peace agreement with Pakistan brokered by the USSR in Tashkent. Under these circumstances, Dr Zakir Husain completed his tenure as the vice-president in 1967. By now, Indira Gandhi had taken over as the prime minister and wanted Dr Husain to become the president, which he conveniently did.

Though his tenure as the president of India was short lived as he died in office in 1969, Dr Husain’s overall contribution to bring peace and harmony to an India that was still recovering from the aftermath of the partition in the name of religion, remains unmatched. His leadership as an educationist and education manager, both at Jamia Millia and Aligarh University, was a shining example of how a dedicated professional can transform the minds and hearts of the people torn apart by religious divisions.

Dr Zakir Husain’s books, especially Dynamic University, outline his ideas about education that is free from prejudice and indoctrination. His translations of Plato in Urdu are still worth reading. By 1969, when Dr Zakir Husain died in office, India had seen three presidents -- Dr Rajendra Prasad, Dr Radhakrishnan, and Dr Zakir Husain -- all possessing doctoral degrees in various disciplines. And by that time Pakistan had seen heads of state such as Ghulam Mohammad, Major-General Iskander Mirza, General Ayub Khan, and General Yahya Khan.

It is interesting to note that Dr Zakir Husain’s younger brother, Dr Mahmud Husain, was a supporter of Pakistan and migrated from India to serve as federal education minister just for one year before Khawaja Nazimuddin’s government was dismissed by Ghulam Mohammad. Dr Mahmud Husain never returned to politics and founded another Jamia Millia in Karachi. But unlike Jamia Millia in Delhi, the Karachi one could never become a centre of higher learning and declined rapidly after its nationalisation (read bureaucratisation) in 1972. This scribe being an eye witness to this decline as a school student there in late 1970s. Dr Mahmud Husain also served as the vice-chancellor of the University of Karachi in 1970s.

When Dr Zakir Husain died, vice president VV Giri became the acting president, pending elections for a new president. Giri wanted to run for president, and for that he had to resign, but there arose a constitutional problem. Where was he supposed to submit his resignation, there were no president and vice president, and he himself was the acting president; the constitution makers of India had not anticipated such a situation. So a new law was brought in, making a provision for the Chief Justice of India to step in, if there are no president and vice president. That’s how Justice Hidayatullah became acting president of India.

Justice Mohammed Hidayatullah was a lawyer par excellence and had the distinction of being the youngest chief justice of a high court and then the youngest judge of the supreme court of India. He was appointed the chief justice of India in 1968 by President Zakir Husain, and that was an interesting time for India when both its president and chief justice were Muslim. A memorable event of Hidayatullah’s brief presidency was the visit of American President Richard Nixon, whom he received as his counterpart. Almost ten years after his retirement, Hidayatullah was elected vice-president of India in 1979.

The next Muslim president of India was Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed who took over from VV Giri in 1974. FA Ahmed was born in Delhi but his family belonged to Assam. During Nehru’s period, Fakhruddin was mostly involved in the Congress politics in Assam but when Indira became the prime minister, she brought him to the capital, making him first the minister of industries and trade, and then minister of agriculture.

The worst part of Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed’s tenure as the president of India was the declaration of the state of emergency by Indira Gandhi throughout the country. Indira Gandhi was known for her political ruthlessness and over-centralisation of power, and Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed allowed himself to be used as a rubberstamp to impose the state of emergency in his name. Officially issued by the president, emergency remained in force for 21 months from June 1975 to March 1977. This allowed Indira Gandhi to rule by decree, and authorised her to suspend elections and curb civil liberties.

Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed remained silent when most of the political opponents of Congress were put behind bars and press was censored. A mass-sterilisation campaign was launched by Indira’s son Sanjay Gandhi, but the president was nonchalant.

Fakhruddin was as impotent as in Pakistan we have seen presidents Fazl-e-Ilahi Chaudhary and Rafiq Tarar, who were selected more for their loyalty and submission than anything else; a couple of more examples will be added to the list as history progresses.

Probably the pressure of emergency was too much, or the guilty conscience was chipping away his energy, Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed died in February 1977, in the same bathroom of the President House where Dr Zakir Husain had collapsed eight years earlier. Interestingly, up until now two presidents of India have died in office without completing their term, and both happened to be Muslim.

Now we come to the third Muslim president of India, APJ Abdul Kalam, who not only completed his term in 2007 but even hobnobbed with the BJP for another term in 2012 when President Pratibha Patil completed her tenure. Without sufficient support, he gave up his interest in another presidential election.

When Abdul Kalam was elected as president in 2002, it was BJP’s government and Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee was looking for some green shade over his saffron base. Abdul Kalam had the highest credentials as a Muslim scientist with Bharat Ratna, India’s highest civilian honour, already in his treasure. He had played an instrumental role in Pokhran II project under which the nuclear devices were detonated in 1998. Who could serve the BJP better than a Muslim scientist who had helped India to arm itself to teeth?

The Indian National Congress did not nominate any candidate to contest against Kalam; but the four leftist parties did not leave the field open. The Communist Party of India, the CPI (M), the Revolutionary Socialist Party, and the Forward Block nominated 88-year-old Lakshmi Sehgal -- a former revolutionary and freedom fighter -- who lost against Kalam by a wide margin and Kalam became the 11th president of India in 2002.

Abdul Kalam belonged to a very humble background. His father was a boat-maker in a town near Madras (now Chennai) in a southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu. Kalam worked extremely hard to win a scholarship to one of the top Indian Institutes of Technology. His entire life is a story of tireless efforts and singularity of purpose; he earned the highest possible accolades for his outstanding contributions to science and technology in India.

But, unfortunately a scientist of his repute stooped to the level of a blind nationalist who overlooks the power of his destructive innovations. Of course, had he not supervised the atomic blasts in 1998 or the development of Indian missiles, somebody else would have done it; just as in Pakistan had AQ Khan not done it, Samar Mubarakmand or somebody else of his ilk would have done it. The point is which side of the fence you stand on? You develop science and technology for peaceful purposes, or you hide behind euphemisms such as ‘arms for peace’ and ‘bombs for brotherhood’ and in reality you pile up hatred and promote jingoism.