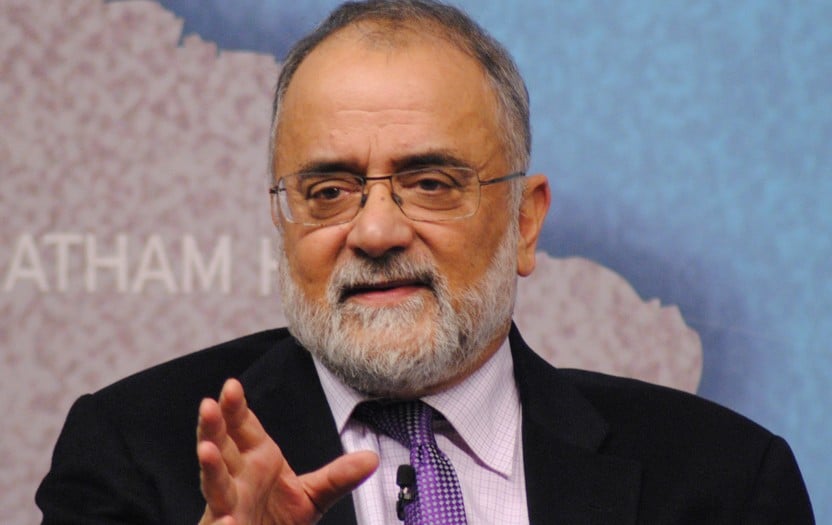

Ahmed Rashid analyses Iran’s nuclear deal, focusing on its possible impact on the US and the Middle East region

The News on Sunday (TNS): Give us a background of this nuclear deal with Iran?

Ahmed Rashid (AR): The starting point is the 1970s when the Shah of Iran was literally anointed as the policeman of the Gulf by the Americans. He was used to suppress the Marxist insurgency in Balochistan as also the Marxist insurgency in Oman. He terrified the Arab states which were in the 1970s in a very weak position (Oil had just been discovered and they were not as powerful as they are now). So the relationship greatly determined the American presence in the Middle East. And remember the Shah was very friendly with Israel.

That is what history tells us -- that there is a natural partnership between Iran and the United States. And restoring that [friendship] is going to be surely the aim of this administration and the next administration. The question now is that the Americans can not afford to antagonise their Arab allies.

TNS: But then how does one explain the intervening years from 1979 to the present times?

AR: In the intervening years, the whole social and political system changed in Iran -- it became anti-West and anti-American. That is the legacy which is not going to disappear overnight, no matter how pro-American the Iranian people may have become. The political system is not going to allow them to do that. It is going to be a very difficult path forward.

Now, for the first time, all other allies of the Americans including the Arabs are opposed to this deal. And you have the Arabs and Israel lining up together. That is more complicated for the Arabs and the Arab-US relationship.

The question is: who, at the moment, has more to deliver for the United States and the West in terms of crushing the ISIS, in terms of stabilising Iraq or Syria -- the Arabs or the Iranians? Clearly, it is the Iranians who have more to deliver: Iran is bolstering the Iraqi regime; it is providing troops, money, and guidance through the revolutionary guards; Iran is the main backer of President Assad of Syria and has provided thousands of troops, Hezbollah and money, etc; Iran is supporting the opposition in Yemen. So, at the moment, Iran is the protagonist in all these conflicts. It certainly has the power and capacity to bring peace to the region.

So, I think the Americans will weigh up and start the dialogue process with Iran regarding these other issues very quickly because there is no other option. The West is not prepared to put troops on the ground. They don’t have a decent foreign policy in the region. Hence, they are more dependent on Iran than anyone else.

Now, one attempt will be made to make peace between Iran and the Arabs, and between Sunnis and Shias to reduce this Sunni-Shia conflict. But [for that] Iran has to deliver on either peace in Syria or peace in Yemen or peace in Iraq. And it has to show its determination to crush ISIS. Then maybe the Americans can persuade the Arabs and say, look Iran is now no longer such an enemy; it is doing some god things which are benefiting the Arabs.

TNS: But that does not look likely…

AR: I think the process will begin very soon. The Americans are quite desperate since the situation in the Middle East is getting from bad to worse. Assad is crumbling and the choices in Syria are awful; it is one extremist group or the other. I think we will see a quick behind-the-scenes move. In Syria, what can Iran do to give Assad a graceful, not a humiliating, exit? I think the Americans will buy that -- a graceful exit and to put into power a coalition of moderate Syrians and not allowing the extremists to come into power in Damascus. All this, you might think, is very much up in the air at the moment but I think the West is getting more and more desperate. Especially, if they are seeing, as I see, that Assad may fall in the next two months.

TNS: The way you put it, it looks as if the deal is less about nuclear bombs and more about peace in the region.

AR: I am only discussing the geo-political aspects. Don’t forget they [Americans] have to retain the friendship of Israel. And the only way they can do that is to fulfill all the promises being made. It is a very complicated relationship. The Americans have to make sure the Iranians fulfill the nuclear obligations. Otherwise, Israel will link up with those extreme Arab states who want to bomb Iran. That will be a very dangerous situation.

Secondly, don’t forget that Iran wants the sanctions lifted so that it re-establishes its economy which has completely collapsed. It needs investment, it needs new technology for the oil industry, weapons and it needs to sell oil and gas to new markets. That is where Pakistan and the huge energy-starved South Asia and Central Asia come in -- Afghanistan, Pakistan and India -- which would be crying out for Iranian oil and gas.

TNS: Moving on from the post 1979 scenario, does the US want a balance of sectarian power in the region or has it, as Robert Fisk says, taken the Shia side?

AR: It isn’t with this deal with Iran [that they took the Shia side]. They took the Shia side with the invasion of Iraq. What they failed to understand in Iraq was that the majority of people were Shia and if they overthrew Saddam Hussain, they would automatically bring about a Shia regime. They didn’t understand what that meant -- that the Sunnis would be alienated, they would become extremists, that the Shias would be as chauvinists as Sunnis were before, that there would be no accommodation of the Sunnis.

I don’t think it is now that they have taken the Shia side. There was Shia extremism after the Iranian revolution: the Iranians were trying to export the revolution all over the Muslim world and creating a lot of unrest. The extremism today is Sunni-inspired: the Shias are seen as more or less the victims; they are the victims in Pakistan, they are the victims in Afghanistan -- the Hazaras; as minorities in other Arab countries, they are the victims of ISIS.

There is a natural sympathy in the West for the Shias. But I don’t think it started now; it started with the American mistake in Iraq. The big change with President Obama, unlike with Bush or Reagan, is that there is no desire for regime change. The Americans are not talking about regime change in Iran. And this is because the Bush policy of wanting regime change in the Muslim world collapsed. Despite all the troops and resources going into Iraq, look at the mess Iraq is in. The same goes for Afghanistan. So I think the Americans have learnt that lesson.

Why I am giving you a more optimistic view of Iran and US cooperation is that Iran is now convinced that whatever they do with the US, they [Americans] are not looking for a regime change; they are not trying to overthrow the mullahs. They have accepted that if there is going to be a regime change, it has to come from the inside, not from the outside.

Also read: Diplomacy wins

TNS: How has this deal gone down within America? It is being said the US did not sell this deal well domestically.

AR: We have to understand that foreign policy is not part of this election campaign. In the US, foreign policy plays a very minor role; most people don’t even understand it.

TNS: But the public pressure could lead to different kind of results in the Congress.

AR: The divisions on this policy are along classic American political lines. The Republicans, the right wing, oppose it. The right wing is pro-Israel and anti-Iran. And remember the whole Iranian revolution took place during the Republican administration. That is the kind of revenge they want on the Iranians; they don’t want to do the Iranians any favours. The Democrats, on the other hand, are supporting it. The Democrats don’t control Congress anymore and they are in a much weaker position. As far as the American public is concerned, I don’t think the majority even understands what this deal is about.

TNS: What about looking at the deal in the context of America’s reduced dependence on Middle Eastern oil?

AR: I think that is a very important factor. America is now self-sufficient in oil production. But it is also obligated to protect the sea lanes of the Gulf for its allies who are not oil-sufficient, for example, Japan and countries of the Far East that are all allies of the US and dependent on Gulf oil.

Most importantly, what we are seeing is definitely a US retreat from this region including Afghanistan and Pakistan. There is an unwillingness to get involved, apart from one or two key items.

About the retreat from the Middle East, we know for a fact that there will be no more troops on the ground. That I think is the first step in a retreat from commitments in the Middle East, which the Americans increasingly feel should be taken up by the Arabs. If the ISIS is to be defeated on the ground, it should be by Arab troops and not the US troops.

Personally, I don’t feel the Americans can retreat or withdraw from the Arab world so much -- it will always be dragged back because of its defence of Israel. And American elections and the Jewish vote come into play in a very important way. The Arab anger is based on the fact that they are withdrawing from the Middle East.

TNS: Do you see the Russian influence on Iran changing due to this deal?

AR: I think that is a very important question. I am sure the Russians are quite worried as to what kind of friendship the Iranians are going to strike with the Americans. Don’t forget, Russia and Iran’s policy on Syria and Iraq is the same. So the American effort would be to try and peel away Iran from that relationship with Russia and get Iran to back a peace effort in Syria, and not just go along with Putin’s policies.

So, it is a complicated relationship. The question is what the Iranians think they can get out from an improved relationship with the US? Can the Americans deliver more than what the Russians can deliver? Will the Americans, for example, deliver weapons and technology, and improve the oil industry, allow business, etc? The Russians can’t do a lot of those things because they are under sanctions by the Europeans.

I am being positive on this thing. The Republicans will try to hold US back from having a more positive relationship with Iran. The domestic constraint for Obama will be to not get too far, not to engage too quickly with Iran but to go slowly. We don’t know what’s going to happen with the vote. The Congress is controlled by the Republicans. Obama is going to veto it more likely. A no-vote will show a real division in the American society.

TNS: There is a lot of optimism in Pakistan about the deal?

AR: Pakistan’s optimism is largely based on the energy factor: if the sanctions are lifted how soon can this Iran Pakistan pipeline be built. Then I think there would be oil. And then the whole India factor comes in. The Indian Punjab is very much energy-deprived. Iran does not want to be confined to the Pakistani market: it wants to sell in India. So, that brings in the whole Indo-Pak factor. Will Indians trust us and will we trust Indians? Will India trust the pipeline which runs through Pakistan?

To my mind, the major thing in this whole pipeline business is the security in Pakistan itself. You’re crossing half of Balochistan which has got an insurgency; you cannot expect people to build a pipeline and all.

It is not good enough to say we would crush the Baloch. We have been trying it for ten years and not been able to do that. So you should talk to the Baloch and give them a heavy chunk of the benefits of this deal.

TNS: It is more important to talk to the Baloch also for the Chinese Pakistan Corridor.

AR: It is more important but it does not look like they would. The army says it is going to raise a [security] force of 10,000 personnel. Now that does not show they would actually talk to the Baloch: it means they are still going to pursue a militarised policy. As for protecting the Chinese, one can’t be sure: in Makran, Gwadar, and Fata, Chinese engineers have been killed.

TNS: Will good relations with Iran improve the sectarian situation in Pakistan?

AR: Unfortunately, the sectarian situation with the ISIS has become much worse. And it is no longer relegated to Iran, Pakistan or even Saudi Arabia. ISIS has brought a whole new dimension to this sectarian crisis. In the 1980s, you could be an Iranian proxy or a wahabi proxy. That is no longer the case. Now the ISIS is committing brutalities against all minorities. They want to commit genocide against all Shias -- their physical elimination. Even in the worst days of the Taliban when they were attacking the Hazaras in Afghanistan, it was a punishing campaign against Shias, not a genocidal campaign.

The online version of this interview has been edited for language and grammatical errors.