From doctrine of necessity to basic structure of constitution, the challenges the nation faced 60 years ago still haunt us one way or the other

If observers of political and constitutional developments in Pakistan fell asleep in 1955 and woke up sixty years later in 2015, they would have a feeling of déjà vu. Just recall debates in parliament, and questions raised in apex courts during the last five years to compare them with what was happening in 1955. You will find yourself sitting on a plateau, and running in circles for six decades.

Some of the issues you find popping up again and again are: the attempts of the parliament to assert itself, the efforts of civil and military bureaucracy to thwart such attempts, the desire of decision makers -- politicians, bureaucrats, military officers, judiciary and others -- to avoid accountability, almost constant encroachment by different pillars of state on each other’s domains, zigzag movements of constitutional steps, judiciary’s overall soft supplication to state apparatus but hard handling of civilian governments, a never-ending tug-of-war between central and provincial governments, and an incessant inability to decide how, when, and where to create new administrative units, if at all.

In this two-part article, a couple of challenges are discussed that the nation faced 60 years back but that still haunt us one way or the other. Though there is a strong lobby in our country which suggests that we move forward without ‘wasting’ our time on pondering over the past events; one is inclined to submit that any clinical intervention without understanding the patient’s medical history is more likely to fail.

The two events we are talking about include: the doctrine of necessity and the creation of new administrative units. First, some background. We know that in October 1954, Governor General Ghulam Mohammad had dissolved the first constituent assembly that Pakistan had inherited from the pre-partition days in 1947 and that had been unable to promulgate a constitution even after seven years of deliberations. But, it is a fact that prior to its dissolution, the main points of the draft constitution had been agreed upon and had the governor-general not dissolved the assembly, a new constitution would have seen the light of the day within weeks. So, what prompted Ghulam Mohammad -- who had brought in a prime minister of his choice just a year earlier -- to axe the assembly?

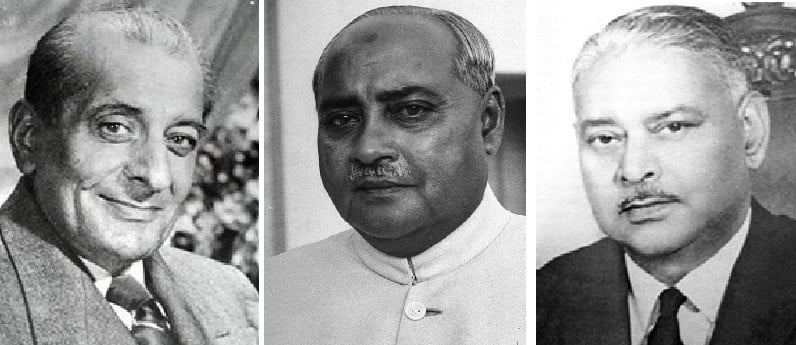

We need to keep in mind that Ghulam Mohammad was born in Lahore and became an accountant by profession. He was a finance officer -- not a politician -- and his elevation from finance minister to governor-general was mainly due to maneuvering by his friends, Iskander Mirza and General Ayub Khan. Khawaja Nazimuddin had fallen into the trap of demoting himself from governor-general to prime minister without realising that he was not liked by the troika of Ayub, Iskander, and Ghulam who would ultimately conspire to remove him. When Pakistan Ambassador to the USA, MA Bogra, was appointed the prime minister, he was a relatively unknown figure in Pakistan because he had mostly remained out of the country holding ambassadorial posts in Burma, Canada, and the USA.

After becoming the prime minister, Bogra feared that the governor-general would dismiss him at his will, just as he had done earlier with Nazimuddin. There was a Bengal-Sindh-Frontier Group in the assembly that wanted to clip the powers of the governor general. There were three major steps taken by the assembly that prompted Ghulam Muhammad to grind his axe. First, in July 1954 the assembly gave power to every high court to issue prerogative writs; second was the repeal of PRODA (Public Representative Offices Disqualification Act), and finally in September 1954 when Ghulam Mohammad was in Abbottabad, the assembly -- through the Fifth Amendment Bill -- took away the governor-general’s powers to dismiss a ministry that enjoyed the confidence of the legislature.

Since the governor-general was in poor health, nobody had expected him to strike back with a vengeance. The Bill was passed in such a haste within hours that the governor had no clue about what was happening in the parliament. Spurred by his success in the assembly, MA Bogra went on his official visit to the US and the assembly was adjourned. The president of the assembly, Maulvi Tamizuddin Khan, is reported to have advised Bogra to stay in the country.

Ghulam Mohammad prepared his plan to get rid of the assembly and in this regard sought help from some of his journalist friends who had previously wrote against Nazimuddin and were now maligning the assembly. Since the Muslim League had lost provincial elections in East Bengal, there was a strong case against the increasingly unrepresentative nature of the assembly. Especially some Bengali politicians were persuaded to issue statements against the assembly. The most prominent Bengali politician from Bengal who demanded the dissolution of the assembly was HS Suhrawardy who suggested that a new assembly be elected by the new provincial legislatures.

Encouraged by this statement, Ghulam Mohammad called Bogra back from his foreign visit and asked him to continue as the prime minister without an assembly. Being civil and military bureaucrats, Ghulam Mohammad, Maj-General Iskander Mirza and General Ayub Khan considered the assembly a gang of goons and wanted to get rid of it. Bogra agreed to the suggestion, reportedly after some reluctance. Ghulam Mohammad placed the country in a ‘state of emergency’ and those who welcomed this decision included the chief ministers of Sindh and Frontier -- Sattar Pirzada and SA Rashid -- Mumtaz Daultana, Mahmud Ali Kasuri and Mir Rasul Bakhsh Talpur.

Ghulam Mohammad appointed ‘a cabinet of talents’ with Bogra as nominal prime minister, but the real power was handed over to Major-General Iskander Mirza as interior minister and General Ayub Khan as defence minister -- both of them were not even members of the dissolved assembly and now thought it fit to deliver preening lectures on how to run a controlled democracy.

In front of these stocky and grim-faced adversaries stood fast a wisp of a man -- Maulvi Tamizuddin Khan, president of the constituent assembly -- who decided to challenge the governor general’s action. The troika tried to entice him to become a minister but he was no venal person; he filed a writ petition with the Sindh Chief Court and pursued it almost single-handedly.

The Sindh Chief Court led by Chief Justice Constantine in a landmark judgement nullified the dissolution of the assembly, restored the petitioner, Tamizuddin, as the president of the assembly and restrained all respondents -- Chaudhary Muhammad Ali, Iskander Mirza, MAH Isphahani, Dr Khan Saheb, General Ayub Khan and others -- from obstructing and interfering with the exercise. The case was heard by Chief Justice Constantine, Justice Vellani, Justice Mohammad Bachal and Justice Mohammad Bukhsh.

Though a lot has been written about the later judgement of Chief Justice of Pakistan, Justice M Munir, not much has been highlighted about the Sindh Chief Court’s decision, probably because it was overturned by the Federal Court whose verdict actually prevailed, irrespective of the merits of the Sindh court’s ruling.

The State of Pakistan had argued on the basis of article 223-A of the Government of India Act 1935 according to which the governor general was to approve of all legislation passed by the parliament and without his signature no law could be deemed to have any legal status. Justice Constantine maintained that the Government of India Act 1935 had been superseded by the Indian Independence Act 1947 according to which the assembly was supreme and no signature was required for Acts of Constituent Assembly by any governor.

Justice Vellani also wrote his verdict that supported the Chief Justice’s ruling, but probably the highlight of the Sindh Chief Court’s decision was Justice Mohammad Bukhsh’s detailed write-up spanning 42 pages in which he totally agreed with Justices Constantine and Vellani and elaborated his ideas about the country’s constitutional framework.

Unfortunately, the federation (read Governor General Ghulam Mohammad) appealed the decision to the Federal Court that overturned the Sindh Chief Court’s verdict on the flimsy ground that the act depriving the governor general of his powers to dissolve the assembly was not valid because it did not have governor’s signature and the Sindh Chief Court could not pass a judgement in this regard.

The lone dissenting voice came from the Agra-born Justice Alvin Robert Cornelius (1903-1991) who belonged to an Urdu-speaking Christian family of UP. He was very candid in his dissenting verdict, he wrote:

"In the given circumstances, there is nothing in the law which makes the grant of assent by governor-general to the acts of Constituent Assembly binding so that its absence may vitiate and invalidate all the laws passed earlier… Constituent Assembly is to be regarded as a body created by a supra-legal power to discharge a supra-legal function of preparing a constitution for Pakistan. Its powers in this respect belong to itself, inherently by virtue of its being a body representative of the will of the people in relation to their future mode of government."

The students of political and constitutional history of Pakistan should not be confined to lamenting Chief Justice Munir’s decision without reading the verdicts of Justice Constantine and Justice Cornelius, the two stalwarts of Pakistan’s judiciary who tried to put Pakistan on the right constitutional track by upholding the concept of parliamentary democracy.

Justice Munir’s decision has had over exposure and most history books on Pakistan have given ample space to it but hardly anything is written about the verdicts given by Justice Mohammad Bukhsh, Justice Constantine, and Justice Cornelius. Especially the names of Justices Constantine and Cornelius should be included in the hall of fame of non-Muslim Pakistanis who refused to follow the dominant discourse and paved the way for others such as Justice Dorab Patel and Justice Bhagwan Das.

Another name that stood out during that legal wrangling is that of II Chundrigar who represented Maulvi Tamizuddin in both the Sindh Chief Court and in the Federal Court. Chief Justice Munir was reported to be particularly hostile and even rude to Chundrigar in response to some of his very well presented arguments; Munir acted as if a politician of Chundrigar’s stature was nobody.

Interestingly, Justice Munir in his verdict did not touch upon the issue of whether governor-general had the power to dissolve the assembly; he solely focused on the question of the missing signature and did not take into consideration highly valid arguments presented by the Justices of the Sindh Chief Court. If you compare the writing of Justices Constantine, Vellani, and Bakhsh with that of Justice Munir, you feel a sense of bathos.

The Federal Court’s decision was announced on March 21, 1955 after which the governor-general assumed to himself the power to enact laws, promulgated an ordinance making some constitutional changes and set up a Constitution Convention in place of the dissolved Constituent Assembly.

While the governor-general was indulging in legislative activism by promulgating ordinances, an important case came up for hearing in the Federal Court. It was known as Usif Patel v. the Crown in which Usif Patel and two other persons had filed constitutional petitions against their imprisonment under an Act approved by the governor-general. While dealing with this case, the Federal Court criticised the action of the governor-general in enacting constitutional legislation and in setting up a Constituent Convention as being beyond his powers. This prompted the governor-general to make a Reference to the Federal Court for determining certain specified issues.

Though Maulvi Tamizuddin case is frequently referred to as a milestone, in fact the Usif Patel Case and the subsequent Reference are of seminal importance for understanding the so-called Doctrine of Necessity. It was through these cases that the Federal Court actually upheld the dissolution of the Constituent Assembly and asked the head of state to bring into existence a representative legislative institution.

The argument was that after eight years the Constituent Assembly had been unable to produce a constitution hence it tended to become a perpetual legislator that had become unrepresentative and needed to be dissolved to pave the way for a new assembly.

Interestingly, the Federal Court adopted the doctrine of civil or state necessity advanced by the counsel of the Federation of Pakistan, Lord Kenneth Diplock (1907-1985). Contrary to common perception, Justice Munir did not come up with the doctrine of necessity, he simply accepted the argument of state necessity presented by Diplock in these words:

"That which otherwise is not lawful, necessity makes lawful and safety of the people and safety of the state is the supreme law… and these maxims are to be treated as part of the law. The best statement of the reason underlying the law of necessity is to be found in Cromwell’s famous utterance: ‘If nothing should be done but what is according to law, the throat of a nation might be cut while we send someone to make a law’."

By embracing this logic, the Chief Justice of the Federal Court, Justice Munir, demolished the legal foundations upon which Pakistan could have become a law-abiding nation. While referring to Cromwell, no mention was made to the fact that just three years after his death, Cromwell’s body was exhumed in 1661 from Westminster Abbey and was subjected to the ritual of posthumous execution. His disinterred body was hanged in chains and then thrown into a pit; his severed head was displayed on a pole outside Westminster Hall until 1685.