The peace talks held in the hills of Pakistan recently enabled the first real face-to-face negotiations between the Afghan government and Taliban

The talks between delegations of Afghan government and Taliban held in Murree on July 7 broke the ice in the long-running conflict that has many dimensions and has brought large-scale death and destruction to Afghanistan.

The Murree talks were a breakthrough in the sense that these were the first real face-to-face negotiations between the Afghan government and Taliban. The earlier meeting in Urumqi, capital of China’s Xinjiang province, on May 19-20 didn’t have so many participants of such a high-level from the two sides.

No US official attended the Urumqi meeting, but an American was present as an observer in Murree. Also, the presence of Haqqani network representatives in the Murree meeting helped broaden the level of representation of Taliban.

In a nutshell, the Urumqi talks were preliminary and exploratory, while those in Murree were a step forward and substantive.

The Murree meeting became possible because the Taliban, on Pakistan’s persuasion, gave up the demand for immediate and complete withdrawal of foreign forces from Afghanistan before agreeing to hold peace talks. The Afghan government and the US also didn’t put any preconditions and also raised no objection on the presence of Haqqani network representatives in the meeting.

There was no concrete outcome in terms of agreeing to a ceasefire or release of prisoners. There was no agreement on halting large-scale attacks as sections of the media erroneously reported. A proposal put forward by the Afghan government for temporary ceasefire during the forthcoming Eidul Fitr festival is still on the table though it appears unlikely.

The one concrete outcome was the agreement to meet again after Eid, probably in August, though the venue was being discussed and it could possibly be China, Qatar or Pakistan. China was said to be keen to play host again, but Qatar will be considered if the Taliban Political Commission could be brought into the dialogue process by exerting pressure on it through the Taliban Rahbari Shura (Leadership Council).

Efforts were made by both sides to ensure that their delegations were all-inclusive with representations from all factions, regions and ethnic groups. Still, some groups went unrepresented and the UN pointed out that women should have been included, obviously in the Afghan government delegation as the Taliban would resist the idea.

The six-member government delegation was led by Hekmat Khalil Karzai, an intellectual serving as the deputy foreign minister and a distant cousin of former President Hamid Karzai. Others included Haji Azizullah Din Mohammad, former governor of Kabul and Nangarhar provinces and presently senior member of the Afghan High Peace Council. He and Hekmat Karzai are both Pashtun and are considered close to President Dr Ashraf Ghani.

Mohammad Asim, who is governor of Parwan province and is an ethnic Tajik, represented Chief Executive Officer Dr Abdullah. Faizullah Zaki, an ethnic Uzbek, was the representative of first Vice President and former Uzbek warlord General Abdul Rasheed Dostum. Asadullah Saadati, an ethnic Hazara Shia was the nominee of second Vice President Sarwar Danish, who is also a Hazara Shia.

Another Hazara Shia delegate was Mohammad Natiqi, who represented Mohammad Mohaqqiq, the former Hazara Shia warlord who is presently the first deputy chief executive office and was earlier the running mate of Dr Abdullah in the presidential election. Zaki and Natiqi are also former members of parliament.

The former health minister Mulla Mohammad Abbas reportedly led the Taliban delegation. It included former Taliban deputy foreign minister Mulla Abdul Jalil, who used to liaise with Osama bin Laden and other al-Qaeda members on behalf of the Taliban, and Abdul Latif Mansoor, the son of late mujahideen commander Mulla Nasrullah Mansoor considered close to the Haqqani network.

Most surprising was the presence of Ibrahim Haqqani, the brother of the Haqqani network founder Jalaluddin Haqqani and uncle of the network’s present head Sirajuddin Haqqani. Giving him company was Yahya Haqqani, stated to be Jalaluddin Haqqani’s son-in-law. Though Ibrahim Haqqani isn’t a wanted man and has no head-money on his name, he certainly represented the Haqqani network, which has been declared terrorist by the US and the UN and whose head Sirajuddin Haqqani and certain commanders are among the most-wanted men with handsome reward money for their capture, alive or dead.

There was no representation from the Taliban Political Commission based in Qatar. A statement issued by the Taliban movement after the Murree talks reiterated that only the Political Commission was authorised to hold talks and carry out internal and external political activities. A similar statement was issued after the first face-to-face meeting between the Afghan government delegation led by Mohammad Masoom Stanekzai and the Afghan Taliban representatives Mulla Abbas and Mulla Jalil.

The statement reflected the sentiments of the Taliban Political Commission headed by Tayyab Agha which felt offended that it wasn’t taken on board. However, the Taliban statement didn’t condemn the Taliban negotiators in Murree and said nothing about Pakistan’s role, apparently not to annoy its powerful military.

However, an article appeared on a Taliban website criticising Pakistan’s role in arranging and hosting the talks, warning that this would have consequences, and telling Kabul that it would soon discover that Islamabad was taking it for a ride.

The article was soon afterwards removed from the website.

Aizaz Ahmad Chaudhry, Pakistan’s foreign secretary, attended the meeting, which became possible due to the leverage of Pakistan’s security agencies on Afghan Taliban. Pakistan managed to ensure the presence of a US and two Chinese officials during the meeting as observers. This gave the event an international flavour and ensured that the talks would be observed by the Americans and Chinese and Pakistan would not be accused of manipulating things. Also, Pakistan would like the US and China to help remove hurdles in case of a stalemate and also become guarantors once the talks make headway and an agreement is reached.

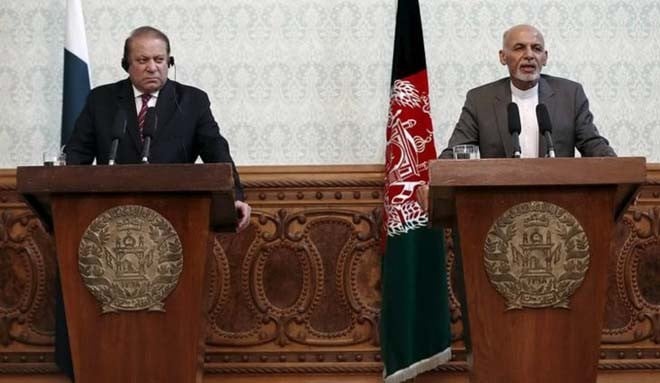

The Murree talks was good news for President Ghani, who had been under pressure to give up his efforts to befriend Pakistan for using its leverage on the Afghan Taliban to bring them to the negotiations table. At their press conference in Kabul after returning from Pakistan, the government negotiators were upbeat about prospects of the peace talks and ready to acknowledge Pakistan’s key role in facilitating the Murree meeting. Deputy foreign minister Hekmat Karzai said he was convinced they had met the right people as the Taliban delegates mostly belonged to the "Quetta Shura" and were authorised by the Taliban deputy head Akhtar Mohammad Mansoor and the Taliban Shura to hold the peace talks.

One could see pragmatism at display when Hekmat Karzai said his government is open to discussing Taliban demands for amendments in the Constitution, deleting names of Taliban leaders from the UN ‘black-list’ and release of Taliban prisoners. However, he stressed that the first and second sections of the Afghan Constitution concerning the rights of the people and democracy won’t be amended. He pointed out the removal of Taliban names from the UN ‘black-list’ could take place if strong guarantees were given regarding their future conduct and confidence-building measures were undertaken by both sides.

Apart from internal and external spoilers who don’t want the Taliban to become shareholders in power or give Pakistan the leading role in the Afghan peace process, the differences in Taliban ranks and among the Afghan ruling elite could also become roadblocks in ending the conflict.

There has been no let-up in Taliban attacks after the Murree talks. The Afghan government has also undertaken some small-scale military operations and the US drone strikes have increased.

Some of the top Taliban military commanders, including Abdul Qayyum Zakir and Mulla Baz Mohammad operating in southwestern Afghanistan, have opposed the peace talks. Other important commanders such as Mulla Mohammad Rasool and Hafiz Majeed too have criticised the peace talks made possible by the change in Taliban policy after having refused to recognise the Afghan government all these years. The differences between the pro- and anti-talks camps among Taliban could widen if the dispute is allowed to linger on.

The uncertainty about Mulla Omar’s fate has added to the problem as he was a unifying figure for Taliban and his words could have been decisive but his voice hasn’t been heard for some years now.

Adding to the problems is the controversy surrounding the Taliban deputy leader Akhtar Mohammad Mansoor, who is being opposed by powerful Taliban military commanders due to a host of factors. If his pro-talks faction makes a deal with the Afghan government, his opponents in the anti-talks group may continue fighting or even align with the Islamic State to keep Afghanistan destabilised.