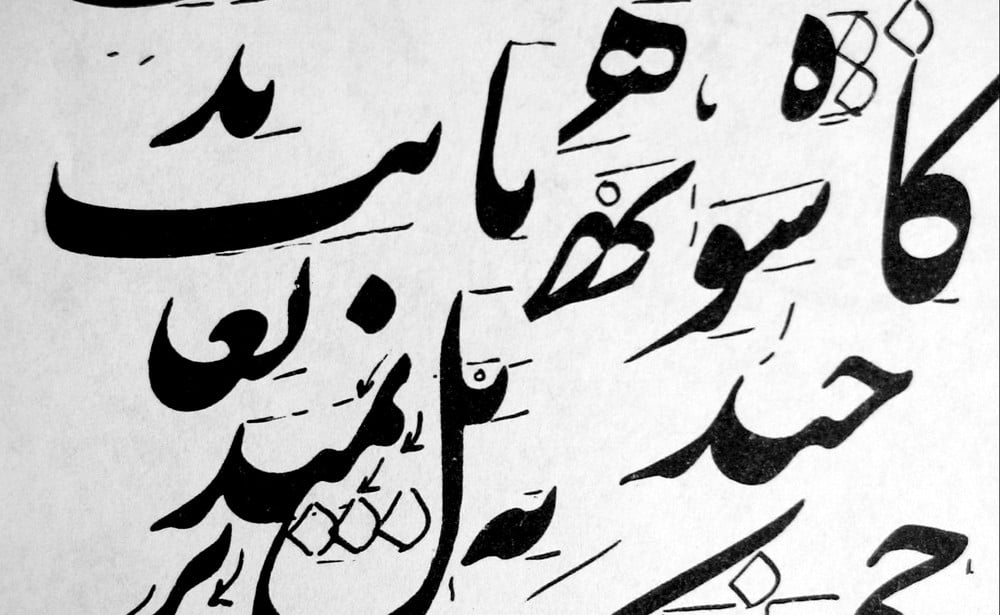

Three prose pieces in Aaj where tone assumes a centrality

I had the good fortune to read three prose pieces in my favourite Urdu literary magazine Aaj. The first story that nudged me to reflect on the issues of tone was Rud-e khanzir by Sadeeq Alam, based in Calcutta. The story deals with a son and his mother who move back to India around the independence of Bangladesh. The young protagonist witnesses his mother go through humiliation and suffering (rape) when they cross into India and afterwards as well as she fights for survival. Death opens up its maw and swallows her forcing the young protagonist to grow up.

The absence of his mother is then soon filled by a washed up prostitute who consoles and is consoled by the protagonist. Sensing her end, she takes him to her ancestral village by a river, which gradually begins to overflow with dead pigs, as she breathes her last.

The tragedy in our hero’s life is precipitated by the betrayal of his father, leaving for Karachi with the promise to return to take them back. The story draws its power from the abandoned child trope on the one hand and on the other from the Madonna/whore syndrome activated twice. The story deals with issues of loyalty, betrayal, linguistic affiliations, suffering of women under patriarchy and so on.

I may be off the mark here but the tone, a mixture of subdued anger and melancholy, is the real character of the story. One detects an erotic embrace of Naiyer Masud and Manto in Alam’s diction. The result is hypnotic with the reader putting her complete trust in the sophisticated monologue -- until a minuscule detail calls attention to itself. During a transaction with the family goldsmith, the mother divulges that she has stopped sending her son to school. There is no evidence that the mother put any effort into the boy’s refined tone. The narrator is semi-illiterate. That casts a doubt as one wonders whether the narrator’s voice is his own or its author’s.

Ikramullah’s wonderful memoir Yaaden raises similar questions. Yaaden opens with the narrator’s admission of fear that a friend from childhood in pre-partition Amritsar must be dead, due to his affiliations with the communist party. The first pages detail a humorous episode about letter exchanges between the narrator and Kapil, the Indian friend. Since the letter had arrived from India, police on this side of the border kept a vigilant eye, resulting in a summon to the police station alleging that words of endearment in his reply were secret spy codes. He is finally released but not before he’s shaken.

This opens up the way for Ikramullah to re-visit his years of youth in Amritsar and also recount the first time he is allowed to visit India with a short stay in Amritsar. The piece is a pleasure to read with so many invaluable human and material details of a bygone era. Although this is a non-fiction piece, Ikramullah is fundamentally a fiction writer. I would even place him among the crème de la crème of Urdu fiction. And since he is one of my favourite Urdu fiction writers, I read Yaaden as if it were a fiction piece.

Despite being a powerful recollection, it inhabits a shaky terra firma due to its unresolved hold on tone. While it opens with the extremely intimate tu in the very first sentence (mera khyal hai keh tu kahin pichchli sadi ke san ikavan bavan main mar gya hoga), the tone nervously shifts from tu to tumhara, tumhare, tumhari, a total of six times in a short paragraph before recounting the comic scene of interrogation. As police interrogation ends, the tu and tum have given way to voh. This uncertainty raises its head throughout the diction and possibly mirrors the collective linguistic psyche of an average Lahori Urdu speaker whose mother tongue perhaps is Punjabi.

Although I realise I may be on shaky grounds here, the issue is raising up.

Most of the recollection is beautifully direct and gracefully sad. There is not enough space here to provide too many examples but one or two would suffice:

or

But direct, colloquial speech is occasionally marred by the high language ornamentation such as qurra-e arz or khanda aavar or tamtaraq. The journey of the narrative from the quintessential tu to qurra-e arz is rather queer. The opening note of tu is Ikramullah’s way of showing alliance to his dead friend’s political philosophy, ishtraqiyat (socialism), but the intrusion of the ashrafiya language lays bare divided loyalty and unsorted class issue.

The third piece is by a Frenchman who has made Pakistan his home. A non-native speaker, his case is different from those Urdu writers whose mother tongue is Punjabi. I assume he did not grow up speaking or hearing Punjabi. Thus he brings a uniqueness which can only come from a total outsider. Zalzalah, call it a novella, manages to be unshackled by the constraints of tone or register while jumping from extreme profane to sacred at will. And that’s been possible because the narrator is the sole creator and arbiter. Characters and events are handpicked as if by a god. A non-linear vehicle employs earthquake both as an actual event in modern history and a metaphor for turmoil in ordinary people’s life.

In 29 chapters, Julien Columeau probes human condition as one views Mt. Fuji, with a typical French cynicism yet this does not distance the reader. Despite having assumed a god-like posture, the omniscient narrator avoids acquiring Camus’ imperial vision. Julien Columeau deploys tone nimbly. And he even occasionally injects Punjabi to undercut the grand Urdu narrative.