Of messages soaked in upbraiding wit, unmasking of pretension and, above all, satirising tragedy

"Somebody in the extended family died. No big deal, he was 87. Still one has to attend. See you soon." I found this in my inbox among other old messages from Abdullah Hussein.

His messages, even one liners, have something in common; they demonstrate his ability to come up with la mot juste. These messages are soaked in his upbraiding wit, unmasking of pretension and, above all, satirising tragedy.

Abdullah Hussein was 84. His death is a big deal. On July 4, he lost an arduous battle with cancer. His loss must be unbearable for his family, and surely unendurable for his friends, unsettling for his admirers and readers, and altogether depressing for Urdu literature enthusiasts.

A few days ago he had posted: "Went in for my fourth chemo. Painful. I hope it would go away. I abhor pain. But then I abhor most of the world and it hasn’t gone away. So there! Writers are an unhappy lot. They want to change the work to their vision and they can’t even begin to make themselves understood. Tragic."

Tragic, indeed; and he bled tragedies on paper. He had tasted tragedies growing up without a mother, losing his father at a tender age, and recovering from a nervous breakdown. Out of that series of personal tragedies came his magnum opus -- Udaas Naslein.

The matchless novel, written in the background of war, conflict and partition, laments tragedies too. It put him on the literary map, won him prestigious awards right off the bat, and since then has influenced generations of readers on both sides of the border.

However, he had had enough of it. Another tragedy, perhaps. He was a published, polished and poised fellow, but bore a burdening dilemma that a writer rarely does. Much like Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses, or Noon Meem Rashed’s flagship poem Hasan Koozagar, Abdullah Hussein’s classic Udaas Naslein became a bone in his throat. He would often complain that his other novels were -- comparatively -- ignored by readers and critics. "Its popularity makes people think that I have written only one novel," he would say.

His short sentences, simple syntax and lucid narration, for which he was unfairly criticised and blamed for "ruining the language", has secured Udaas Naslein a place in line with other classic novels like Tolstoy’s War and Peace. The novel’s greater impression and authority was the reason he was requested by President Ayub Khan to write Qaumi Kitabein. This, of course, didn’t gel well.

For him Udaas Naslein was a lucky strike, since, he said, he had set out to write something else. Thus, he preferred referring to himself as an accidental writer. Though he also solemnly believed that "a novelist is as good as his second novel", so he ended up with another masterpiece, and his personal favourite, Baa’ggh. Decades later, he penned his third libro aptly titled, Naadar Log.

Since this nation has been robbed of its true history by forced official narratives, Abdullah Hussein’s bestsellers did a great service by recording the events and incidents leading up to the rupture of the country and beyond. In one of email exchanges he wrote to me: "I have written about Operation Gibralter in it (Baa’ggh); and I was the first to get proscribed information through my sources and write about Hamoodur Rehman Commission report and put it in at the end of my novel Nadaar Log."

The literary consumption and production followed him abroad where for some time he served the likes of John Pilger behind a bar counter. In the midst of "drinking, and enjoying and wasting time" as he would say, he ventured into another ‘lucky strike’.

Tracing back his footprints, he wrote to me: "I spent almost thirty-five years in England and published two English novels. One, I translated Udaas Naslein, under the title The Weary Generations; it was published jointly by UNESCO and Peter Owen publishers in London; two, I wrote Emigre Journeys, a story about illegal Pakistani immigrants, which was published by Serpent’s Tail publishers in London. BBC2 also made a feature films based on this story titled Brothers in Trouble, 1996."

Pakistan Television had already produced and aired an 8-episode serial called Nasheb based on Abdullah Hussein’s short story. He had managed a copy of both, the series and the feature film, and we had planned to watch them together. He messaged me: "It so happened that I had lost my copy of that [BBC serial] too (again the same syndrome -- rogue borrowers). I don’t know whether you have seen that film, but it’s a good one and next time you come to Pakistan we can watch it together."

Abdullah Hussain had a mix of these two cultures in him. He had a deep rooted South Asian customary humility, and inflated sense of hospitality. Yet, he had developed and maintained Western mannerisms where he respected personal space and exercised absolute discipline. He would invite you with all his heart, and serve you, personally, with all his warmth; and would rightly expect you to be on time and somewhat erudite. He’d have the final word, though: "There are scenes of typhus in Doctor Zhivago, which was much after Napoleon, but there is no mention of it in War and Peace, which dealt directly with Napoleonic wars," he wrote to me about the War in 1812.

Read also: Abdullah Hussain -- off the beaten track

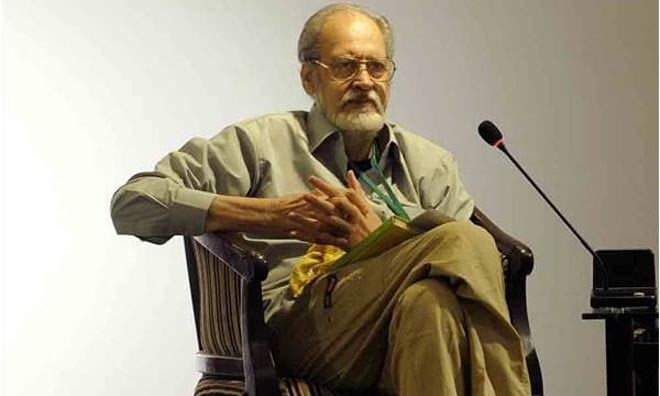

It’s peculiar that people can spot known Urdu writers, probably because of their consistent presence on media, but most of Abdullah Hussein’s admirers had not seen him up close; and almost all of them visioned him to be a short stocky guy. Hence, it was always astonishing to find a tall -- almost 6 feet 4 inches --lean man, with fine cut beard, wearing sneakers. The only thing that could top that was his high-minded but inclusive sense of humour.

As a reclusive author, he would mostly spend time in the pursuit of private pleasures like reading and writing. Lately, however, he had started, quite grudgingly, attending literary festivals and events -- and that too after much convincing from his comrades.

He was active on Facebook as well. His posts and commentary on politics and social injustice were brusque and insightful. There was an odd news item published earlier this year. It said: "Donkey population has swelled in 2015". Abdullah Hussein commented on his page:"We want numbers: how many are doing an honest day’s work. How many are earmarked for the butcher to be sold as prime breed, how many have gone into the Assemblies and so on."

A few weeks earlier he had posted: "Mastung terrorists ka moonh-tor jawab dingay. Karachi murderers ka moonh-tor jawab daingay. God! We don’t need electricity. We need new cliches."

But Abdullah Hussein was only half cynical; the other half of him was valiant and at times a bon vivant. He cherished everything beautiful and honestly hated everything ugly in society and in the world. He would also get surpassingly generous in his appreciation of the people he loved. In 2013 I had written on the sad demise of Shafqat Tanvir Mirza. He read the article and posted: "I officially authorize you to write my obituary as and when the time comes." This, of course, sent a chill down my spine. I could only say that I prefer to celebrate his life and work while he’s still with us.

This explains that he was intensely aware of his growing age. In one of the conversations he had responded: "The passing of life makes failures of us all -- because so much is always left to do." And there was still so much to do. He had just finished writing a long novel in English about Afghanistan; and was excited to get it published.

I knew and admired Abdullah Hussein for years; and I was inclined to be overcome at the number of occasions, where his bearing was so exemplary and his kindness such a privilege. He had asked, "Don’t keep calling me ‘sir’ -- makes me feel as if I’m dead. It’s not true, I’m only half dead". So, Rest in Peace, my friend. Your energy remains stirring and awe-inspiring.