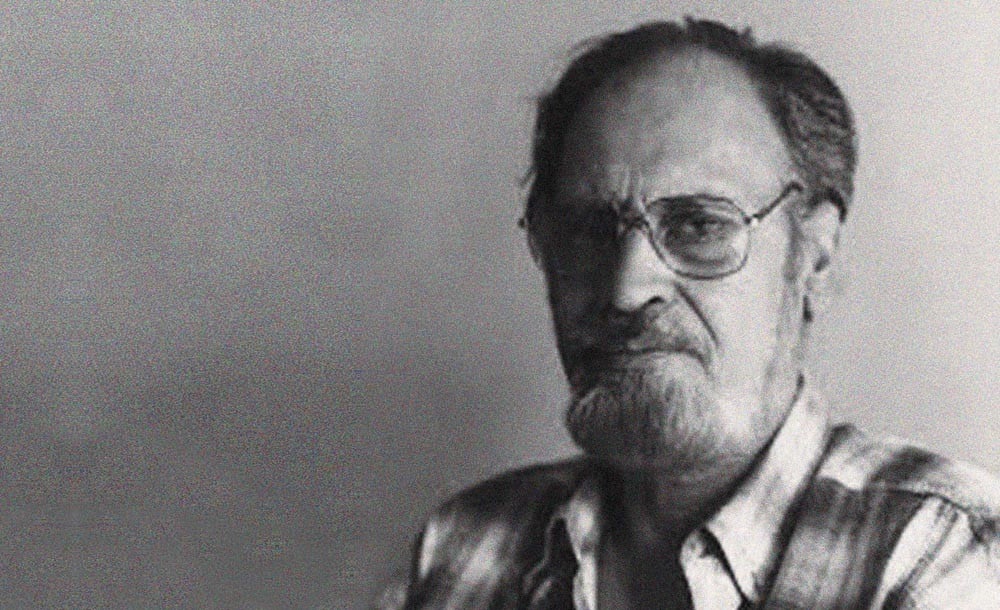

How does one capture a friendship of two generations with a man who lived a life of several generations?

As I scrolled down my Facebook page the other day, my eyes were stuck at a message posted by novelist Abdullah Hussein’s daughter Fatima Noor warning friends and family that he had gone into coma and was struggling for life against blood cancer.

Wasn’t it just a couple of weeks ago that he had posted a message on social media complaining about fatigue from his chemotherapy? It didn’t seem he would vanish one day -- Abdullah Hussein, the storyteller of generations who had the capacity to reach across generations. When I wept, it was not just personal tears but those of at least two generations -- my mother’s and mine.

I became familiar with Abdullah Hussein when it was nothing but only a name for me. I was a child and would often hear my mother and novelist Jamila Hashmi and many of her friends in Lahore talk about him. I recall the debates among these elderly people that left me with the impression that they were talking about a man whose other name was Udaas Naslein.

Oddly, I missed him in 1979 when my mother went to meet him in London. What did I have to do meeting such serious people especially if I could avoid it? Little did I know then that this was one of the rare friends and contemporaries of my mother who would become a personal friend, with whom I would develop an understanding despite the difference in years. It was actually even a bigger coincidence that we touched each other’s imagination especially after my mother’s death in 1988.

Udaas Naslein waley Abdullah Hussein appeared on my radar not before 2004. After my sudden heart attack and heart surgery, I had to stop writing my opinion piece for a few months for the English daily that I used to write for. I then saw a letter to the editor by a name that was part of my memory, expressing concern about my health and the fact that I wasn’t writing. We didn’t meet in person until June 2013 at a ceremony organised by the Academy of Letters to discuss his work. By then, we were good friends connected through cyberspace. He was indeed a man with a big heart, not just in terms of what he created but also how he treated people.

Unlike many men and women of letters of his own generation, he was rare in keeping abreast of the world. An avid reader, he honestly engaged with ideas. While many of his generation shied from stating their candid opinion, he expressed what he felt. Perhaps he was daring with his emotions as he was with his life and mind. He certainly did not belong to the beaten track.

In the mid-1970s, he temporarily migrated to London where he ran an open house and often entertained his friends with stories he had collected of people’s lives from those years. Again, in this very spirit of adventurism he translated his own work Udaas Naslein into English. When very few people chose to deviate from the language and structure of Urdu novel, Abdullah Hussein produced one of the masterpieces that told the story of the partition, connecting it with an older generation dating back to the First World War.

While the partition literature in Urdu was predominantly about stories from Muslim minority provinces, he wrote about Punjab. In doing so, he also experimented with the language of an Urdu novel, a fact derided by many of his contemporaries. We forget that language is a living organism -- it breathes, speaks, sings, laughs and cries, much like humans. It changes and requires people with vision and courage to introduce newer colours and flavours to a given language.

Read also: Rest in peace, my friend

Another of his novels, Nadaar Log, which is a commentary on Pakistan’s political malaise, its bureaucracy and establishment, received lesser attention than his first work but it exhibited his capacity to engage with new ideas. He certainly didn’t shy away from expressing his politics. You could often find him lamenting the state of politics and the gradual death of liberalism in Pakistan. While many of his generation would limit their suspicion of the growing influence of religious right in the country, he wrote about his deep desire to see a pluralist country where people would not judge the other or condemn them to death on the basis of faith.

Perhaps my tears on Abdullah Hussein’s death are not just an expression of agony on the loss of a person but also a deeper lament of how our ignorance deprives us and the generations to come of the works of the likes of him. While he was almost grudgingly invited pretty late to the literary festival circuit, there are other equally big names like Nisar Aziz Butt, Altaf Fatima, Umme Ammara, and Khalida Hussain who are alive, yet ignored.

I remember a recent conversation with a literary critic who complained that despite the proliferation of writers who could write comfortably in English language, the magic and fire was missing. But great literature is not just about inner genius or new ideas; it is a process in which the fiction of today also carries the spirit of what many others had imagined before. We sadly are so ignorant of our legacy. In a society that operates through the yardstick of brand names alone, I really wonder if the loss of a great novelist like Abdullah Hussein would sink in?