A historical overview of the Great Charter seen through the prism of literature and films, and looking at today’s Pakistan in that context

No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions, or outlawed or exiled, or deprived of his standing in any other way, nor will we proceed with force against him, or send others to do so, except by the lawful judgement of his equals or by the law of the land.

To no one will we sell, to no one deny or delay right or justice

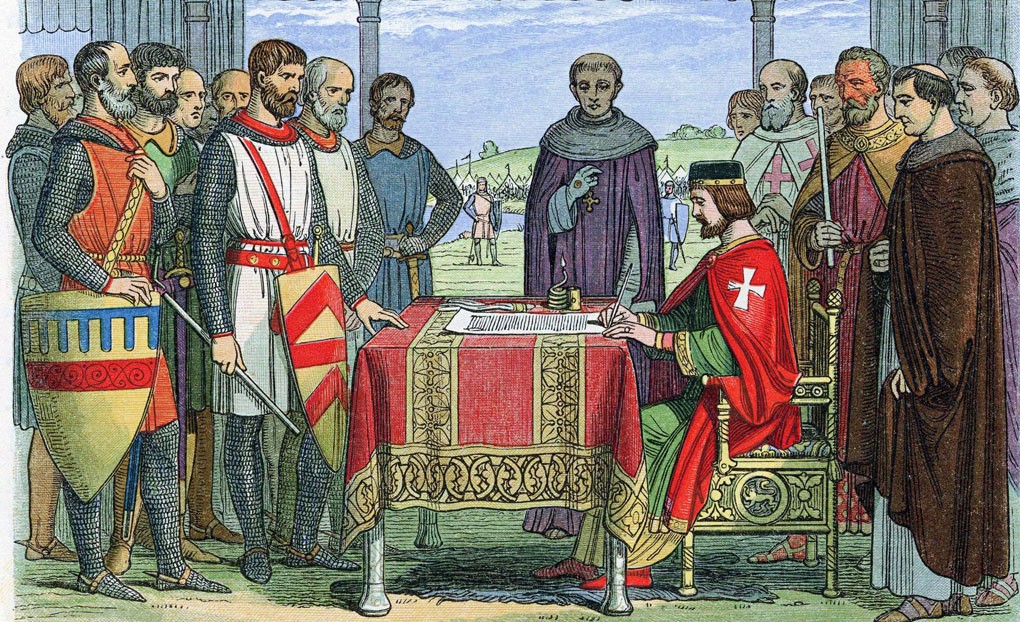

This year the world (mostly Anglo-Saxon) is celebrating the 800th anniversary of the signing of Magna Carta -- the Great Charter. Magna Carta that symbolises some of the fundamental principles of democracy and human rights -- just two of them quoted above -- enjoys an iconic status in the annals of political science. King John, who signed this document in 1215, never intended to put his pen to something that would become such a lasting declaration of legal principles.

Some of the precepts enshrined in Magna Carta are still a far cry from that which we receive in the developing countries such as Pakistan even today. How does one make sense of a charter that has more than five dozen clauses or articles used eight centuries ago as a practical attempt to solve a political crisis?

To understand most political documents of historical significance, an overall picture of the context is vital. In this particular case, an overview of some of the affairs of the 12th century might help us: a Europe that was still lingering in the shadows of the Dark Ages; a clergy trying its best to retain as much spiritual and temporal powers as it could; ruler after ruler attempting to curtail religious dominance in society and in this process sometimes acting even more stupidly than the monks; pope after pope enticing people to launch crusades against the infidels; fight after fight over the possession of holy places; and last but not least the emergence of an assertive segment of society that started resisting the absolute powers of rulers to impose taxes and bleed the country in the name of wars.

Before going into the specifics, probably a non-traditional way of grasping history may be useful such as through literature and films. Here the reader may be encouraged to browse through fiction, fable and the flicks. The first is a play, Murder in the Cathedral -- a verse drama by T S Eliot (1888 - 1965) -- about the assassination of Archbishop Thomas Becket in Canterbury Cathedral in 1170. The play deals with an individual’s opposition to authority that was as relevant in the 1930s -- when Eliot wrote it -- as it is today.

The action takes place in December 1170, during the days leading up to the martyrdom of Thomas Becket following his absence of seven years in France. The play chronicles Becket’s internal struggle and his external fight against the rise of temporal power. Four knights arrive in the Cathedral; these knights had heard the king speak of his frustration with Becket, and had interpreted this as an order to kill Becket; the knights break in and kill him. The chorus laments:

The land is foul, the water is foul, our beasts and ourselves defiled with blood.

At the close of the play, the knights address the audience and defend their actions. The murder was justified and in the right spirit, so that the church’s power would not undermine stability and state power. The play beautifully portrays the tussle between the spiritual and temporal forces in the medieval ages. The king had once been Becket’s closest friend and had made him archbishop in the hope that he would toe the king’s line but, on the contrary, Becket’s maintains the primacy of the spiritual order over temporal.

The same story is presented in the 1964 movie, Becket, directed by Peter Glenville. With Richard Burton as Becket, Peter O’ Toole as King Henry II and John Gielgud as the King of France, how could the movie fail? It didn’t. The movie is much broader in scope thanks to the possibilities of the moving camera as opposed to the limitations of theatre.

The movie begins by establishing the historical fact that King Henry II and Thomas Becket were lifelong friends regardless of the differences in their rank and background. The king finds in Becket a confident adviser and a loyal subject; a rarity among the barons who serve the king. The king’s constant conflict with the church results in financial problems due to the clergy’s refusal to contribute to the king’s efforts to recover lost territory in France. The church jealously guards the tax-free status given to it by previous monarchs. The king tries to change the status quo by appointing Becket as Archbishop of Canterbury, but to king’s dismay his friend changes dramatically after his appointment at the church and becomes loyal to his new position rather than to the throne.

For Pakistani readers this situation should not be surprising; just remember the changing loyalties of our generals, judges, and politicians who are appointed by the ‘competent authority’ in anticipation of continued loyalty but a changed situation puts them in confrontation with their former bosses.

On the journey to Magna Carta, our next milestone is in 1183 presented in the play by James Goldman -- The Lion in Winter. Now almost two decades after his confrontation with Becket, the old King Henry II has three sons -- all wanting to inherit the throne. This play was also converted into an Oscar-winning movie by the director Anthony Harvey in 1968, starring Peter O’ Toole, again as the King; Katharine Hepburn as his wife; the young debutant, Anthony Hopkins, as king’s son, Richard -- later to become King Richard the Lionheart; and Timothy Dalton (who would later succeed Roger Moore as James Bond in the late 1980s) as the king of France. With a cast such as this, the movie was bound to be a success, and it was.

Our next literary source to understand the 12-century England is Ivanhoe, a historical novel by Sir Walter Scott published in 1820 and adapted into a movie by Richard Thorpe in 1952. Again with a star cast of Robert Taylor, Elizabeth Taylor, and Joan Fontaine, the movie is the story of one of the remaining Saxon noble families in England.

The story is set in 1194, after the failure of the Third Crusade, when many of the crusaders were still returning to their homes in Europe. King Richard, the son of Henry II, has been captured by Leopold of Austria on his return journey to England. Ivanhoe had accompanied King Richard on the Crusades against Saladin (Salah Uddin Ayubi) and later helped in his release from Austrian kidnappers. The novel and the movie take liberties with history but help us understand the constant tug-of-war between the Normans (the French conquerors who settled in England after their victory in the Battle of Hastings in 1066) and the Saxons (the locals who were suppressed by the Normans) in the late 12th century England.

Two more movies that will help the readers interested in that period are The Crusades (1935) directed by Cecil B DeMille; and Kingdom of Heaven (2005) directed by Ridley Scott.

With all this background, now we may turn to Magna Carta itself. Two important events to keep in mind are the election of Pope Innocent III in 1198 and the death of King Richard I in 1199. The new pope sought to enforce papal power over secular rulers and to drive out heretics from the church. His policies demonstrated his power but promoted deep civil unrest. King Richard I, who had been captured, imprisoned, and later ransomed, was succeeded by his brother John, the youngest son of Henry II.

After his succession to the throne, the ensuing wars with France were disastrous for the new king, despite his strong army of mercenaries. The reign of King John was marred by a string of largely unsuccessful and extremely costly continental battles, in which he tried in vain to defend the extensive empire he had inherited from his brother. The enormous expenses of fighting encouraged John to exploit his feudal rights and impose extortionate financial demands on the nobility and royal office-holders.

Add to this the conflict with the pope that led to the papal Interdict of 1208-13 withdrawing all spiritual services by the clergy. An interdict is kind of a censure that excludes from certain rites of the church individuals or groups. King John was excommunicated by the pope in 1209. Like most of the kings in those days or dictators of present day, King John was capricious and arbitrary. He is probably best remembered for issuing -- or rather being forced to issue -- Magna Carta in 1215.

Just like present-day rulers with a propensity for war mongering, King John loved wars and each time he lost a battle he also lost a source of revenue, so that the burden of supporting the next military campaign fell on an ever-shrinking number of tax-payers. Sounds familiar?

Further military engagements inevitably made his financial crisis even more acute and he tried to wring as much revenue as possible from all sources of income. He extracted money from administrators, from the courts, and from the feudal system of land tenure. The more unjustly he behaved, the more he encouraged his opponents to organise themselves against him.

For much of his reign, John was engaged in a prolonged dispute with Innocent III, England’s spiritual overlord. The conflict originated in the struggle to elect a new Archbishop of Canterbury in 1205. John refused to admit the pope’s nominee and drove out the monks of Canterbury prompting the Interdict, as a result of which mass could not be celebrated, the sacrament of marriage could not be received, and burials in consecrate ground were not allowed. In retaliation, John seized the lands and vast revenues of the church and ended up as a spiritual outcast overnight.

In the events leading to Magna Carta, John ultimately had to accept the pope’s nominee as Archbishop of Canterbury, reinstate the exiled clergy and recompense the Church for his plundering of its revenue. The pope became feudal as well as spiritual lord of England and Ireland, but allowed John to rule on his behalf. In January 1215, a group of barons petitioned the pope against excessive taxes by the king. The new Archbishop encouraged the barons to press John to govern within the bounds of custom. The king refused to address the barons’ demands and the barons renounced their allegiance to the king, in effect declaring a civil war, and John ordered the seizure of the rebels’ lands. The barons captured the Tower of London but John kept rejecting their demands.

Finally, with Archbishop’s mediation, detailed negotiations were held at Runnymede, a meadow by the River Thames, and led to an agreement involving many concessions by the king, summarised in the Articles of the Barons, establishing a commission of 25 barons with unprecedented and wide-ranging powers to enforce the king’s compliance and constrain his authority.

The Articles were soon superseded by Magna Carta itself and the barons made formal peace with the king by renewing their oaths of allegiance.

Magna Carta was not a statement of fundamental principles of liberty, but a series of concessions addressing long-standing grievances and condemning arbitrary government; and that’s where its relevance lies today. Most of the clauses of Magna Carta dealt with the limits of the ruler’s right in specific areas of taxation and administration. About 40 of the 63 clauses in Magna Carta focused on the royal abuses of feudal custom, and provided means for obtaining redress by regulating king’s rights.

The arbitrary will of the king was also curtailed in matters of justice and his use of judicial disputes to extort huge fines. An important clause stated that no official was to put a man on trial on the basis of his own unsubstantiated statement; now compare this with the mockery of justice in our times, examples are too many to cite. Even now, 800 years after Magna Carta was signed, we see people being imprisoned, put on trial, punished or even hanged with unsubstantiated statements; what to talk about the families who run from pillar to post just to get a glimpse of their loved ones forcibly taken away by state functionaries. And to top it all you can’t even challenge this.

Magna Carta provided for the election of a commission of 25 barons to monitor the king’s compliance with the settlement and to enforce its terms. The 25 barons were empowered to seize the king’s lands and possessions if he failed to adhere to the conditions imposed on him; the terms (the ToR in modern parlance) under which the commission operated confirmed the whole tenor of Magna Carta i.e. the law was a power in its own right and the ruler could not set himself above it.

Those who remember General Musharraf’s summary dismissal of almost an entire judiciary in 2007; or General Zia’s ordinances putting himself and his orders -- and even the decisions of his military officers -- above any law of the land including the constitution, may read some of the clauses of Magna Carta, and lament the situation we find ourselves in.

The importance of Magna Carta lay in the fact that arguably for the first time in history a king allowed his own powers to be limited by a written document.

If you contrast it with what was happening in our region at that time, you see Ghaznavids and Ghauris ruling in quick succession in the 12th century. You may call them Normans of the subcontinent who brought in new languages and cultural elements into their conquered lands. Just like a new language was being formed in England, first reflected in the Canterbury Tales of Geoffrey Chaucer, we see the first mingling of languages in the poetry of Amir Khusrau.

But on the political front there was no Magna Carta in sight; a Slave Dynasty took over Lahore and Delhi in 1206 in the person of Qutbuddin Aibak (1206-1210) followed by Shams Uddin Iltamash (1210-1236) -- all absolute monarchs who are projected as pious kings in our textbooks but who remained as ruthless in subjugating their people as any other medieval or modern autocrat.

Sadly, no drama, novel, or movie can be recommended to get an idea of that period here. What we have instead is swashbuckling and romantic pseudo historical novels by the likes of Nasim Hijazi, a favourite of Gen Zia who used state media to promote Jihad.

In a way, Pakistan is still waiting for the implementation of some of the relevant clauses of Magna Carta. Clergy is refusing to budge and the state cannot even register all the seminaries in operation and can’t even remove a notorious mullah from a mosque, what to talk about a chief monk such as Maulana Shirani. The due process of law has already been undermined.

Just have another look at the clauses in the beginning of this article and ponder where we stand.