This is concluding column of a two-part series. To read the first part click here.

The more I thought about what Stravinsky had said, the more I realised that this is what virtuosity is all about. It is not the applause you receive at the end of your performance; it is not the adulation showered upon you by your fans and admirers. It is not even the rave reviews you receive in newspapers; it is the moment of self-discovery, the moment when you find you are able to do something you felt you were not capable of -- a moment which so elates you that you feel you, actually, are on cloud nine. Alas! Not having the creative calibre of a Stravinsky, or a Gielgud, I cannot say that I have experienced this sensation too often.

It also made me aware of how easily I used to become pleased with my own work. In my early days as a director, I produced Eugene O’ Neill’s mammoth play, Long Day’s Journey Into Night at the old Alhamra theatre in Lahore. I had worked on the play as much as I could in a four week rehearsal period, then, all of a sudden, the opening night arrived. I do not remember ever having a greater attack of nerves than on that occasion. It may have had something to do with the fact that I was also playing one of the leading parts in the play.

I stood next to Jal Nasserwanjee, my assistant stage manager, whose task it was to pull the curtain. The front tabs of the small Alhamra theatre never parted smoothly; they hiccuped as you pulled them apart and got stuck frequently. If you held the rope at a certain height, and gave it an almighty heave, they parted in one swift motion. Nasserwanjee, looking bleary-eyed from lack of sleep, stood holding the rope in his hands, all but quaking with nerves. I had to calm him down and that helped me settle my own edginess. Fortunately, the curtain parted, for once, without a hiccup.

That evening was altogether an extraordinary experience. Nothing went wrong. There was a strange whiff of approbation in the air. I had thought that the audience might become restless watching a play that lasted nearly four hours but that was not the case. I gave, on the whole, a controlled performance. One reviewer called it a tour de force and I was pleased as punch.

Many years later, during one of those periods when I was out of work in London, I got my come-uppance when I read that Mrs. Patrick Campbell, the famous 19th century actress, (Shaw was one of her paramours) played Hedda Gabler in a provincial theatre. A critic wrote that her performance was a tour-de-force. "I suppose", she said, making a pillow of her arms, "that is why I am always forced to tour."

* * * * *

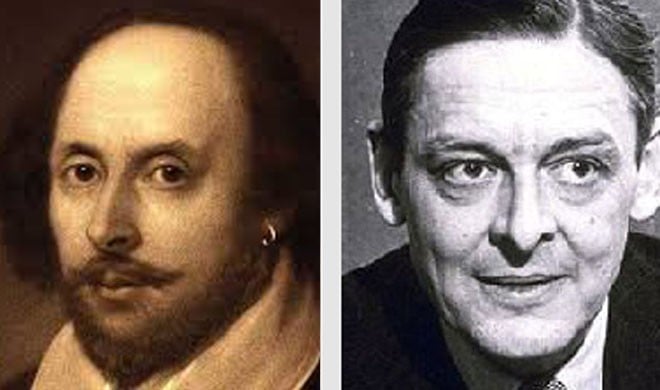

Who would know, better than T.S Eliot, the weight and significance of words? He wrote:

Words strain….

Crack and sometimes break under the burden

Under the tension, slip, slide and perish

Decay with imprecision, will not stay in place

Will not stay still…."

Eliot makes a very interesting point when he says that poetry can communicate before it is understood. People ordinarily incline to suppose that in order to enjoy a poem it is necessary to discover its meaning, a meaning which they can expound to anyone who will listen, in order to prove that they enjoy it. "But," he writes, "The possibilities of meaning of ‘meaning’ in poetry is so extensive that one reader who has grasped the meaning of a poem may happen to appreciate it less, enjoy it less than another person who has the discretion not to acquire too insistently" A comforting thought for most readers of poetry.

Eliot was not enamoured of Shakespeare. He did not think that Shakespeare had a real philosophy. If he had, it was what he called a rag tag philosophy, not one that could have any design upon the amelioration of our conduct and behaviour. We must not forget that T.S. Eliot liked poetry to be deeply Christian and Roman Catholic in flavour. He does concede, however, that Shakespeare made great poetry out of an inferior and muddled philosophy.

Shakespeare may or may not have had a philosophy of his own, but he shows an amazing understanding of the human heart and human behaviour. In his own era, he excited the envy and wrath of the university educated dramatist, Robert Greene, who called him "an upstart crow beautiful with own feathers that supposes he will be able to bombast out a blank verse at the best of us."

Even a cursory read through some of his plays makes you realise that Shakespeare not only understood the problems of the state and the government, the triumphs and failures of historical characters, but also of the rights of individuals and the highly complex religious wrangles. He wrote several plays to please two autocratic monarchs -- Elizabeth and James -- but ever so subtly questioned the divine right of kings.

Shakespeare’s enormous faculty for assimilating the intellectual ferment of his times and fixing it in the matrix of his dramatic situation leaves other dramatists, who followed him, miles behind. This is one reason why, even after four hundred years, his plays are enacted not just in English but throughout the world.

He wrote universal plays of unparalleled brilliance. Othello, Lear, Macbeth and Hamlet are plays that soar above the events of the day. The great tragic or historical characters all learn, in one degree or another, the vanity of power. The mighty King Lear, standing in the great storm, takes heed of all the miseries that had eluded him when he ruled his kingdom.

"Poor naked wretches wherso’er you are,

That bide the pelting of this pitiless storm,

How should your homeless heads and unfed sides,

Your looped and window’d raggedness defend you

From seasons such at this? O! I have ta’en

Too little care of this…"

And Prince Hamlet is painfully aware of "the oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely/the law’s delay/the insolence of office and the spurns/that patient merit of the unworthy lakes/When he himself might his quietus make/With a bare badkin?… "

Shakespeare’s villains suffer because they have sown the seeds of their own destruction rather than the designs of a god or gods. His work contains a whole world and it captures numerous aspects of humanity. In Ben Johnson’s memorable words he was "not of an age but for all times."

But what is it about Shakespeare’s plays which moves us so? I would say it was his understanding of the human heart and of human behaviour. All of this comes across -- I need not tell you -- through words, many of which had never been used before.