A historical perspective of how the power struggle in Egypt, Turkey and Pakistan transformed the social fabric in these majority-Muslim societies

Turkey, Egypt, and Pakistan are not only large Muslim countries located in different continents, they also share striking similarities in their political developments during the past seven decades. An understanding of these developments might help us in drawing a broader picture of civil-military relationships and how they have transformed the social fabric in these majority-Muslim societies. One is fascinated by the almost similar ebb and flow of political struggle the three countries appear to have travelled through.

Turkey has been a bit ahead and if the lonely death and funeral of the 98-year old former general, coup-maker and self-appointed president, Kenan Evren, is any guide, Egypt and Pakistan might also sooner or later head in the same direction. In 2012, General Evren was tried for his role in the 1980 coup and sentenced to life imprisonment in 2014 by a court in Ankara. He was also demoted to the lowest rank of a private. When he died in May 2015, only his close relatives and some military personnel attended his funeral because he was treated as a criminal usurper and not as former commander of the army and the head of state. Political parties sent no representatives to the funeral and a number of people protested during the religious service in the mosque’s courtyard.

The chroniclers of fin-de-siècle politics have called Turkey the "sick man of Europe". At the turn of the century, the Ottoman Empire was breathing its last and then the First World War hammered the proverbial last nail in its coffin. At the end of the war, despite some valiant military feats by Mustafa Kemal (later Atatürk) and his soldiers, the Allied forces had almost forced Turkey to its knees and were bent upon punishing it for its support to Germany during the Great War.

Gradually Kemal Atatürk emerged as the redeemer of his people and with the help of his fighters not only managed to regain some of the lost territories but also ultimately dissolved the Ottoman Empire and put the country on the road to a secular and progressive future. He knew very well that to take his society forward the country had to be extracted from the morass of backwardness.

He became the first president of modern Turkey in October 1923 and gave his country a new constitution in 1924. For the next 15 years he tried to remove the last vestiges of a medieval mindset from his people; struggled against religious dominance in society and promulgated a civil code modeled on the one used in Switzerland. He shut down all religious courts and to eliminate crimes he enforced laws borrowed from Italy. In 1934, he granted full political rights to women and replaced old Turkish script with the Latin one.

When Atatürk died in 1938, his old comrade İsmet İnönü became president who intelligently steered clear of WWII, kept his country neutral and only in the last stage joined the Allies. In 1946, he abolished the one-party rule and introduced a multi-party system in which his party won the first elections and he remained president till 1950. In the next elections the opposition party won and showed him the door. He was magnanimous in his defeat and, establishing democratic traditions, stepped down to hand over power to the Democratic Party of Adnan Mederes and Cêlal Bayar who became prime minister and president respectively.

That’s how Turkey became probably the first country in the Muslim world that witnessed a democratic transfer of power from one political party to another. The credit for this goes entirely to İsmet İnönü and not to the army that immediately started efforts to unseat the newly-elected civilian government. Similar attempts were later witnessed in both Egypt and Pakistan.

After the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, for almost quarter of a century the Turkish army held sway over almost all aspects of Turkish society and, as a true reflection of the military psyche, barely tolerated any dissent. After 1950s, when the Democratic Party tried to deviate from some of the secular principles enshrined in the constitution the army resisted and finally in 1960, General Cemal Gürsel overthrew the elected civilian government and arrested both the president and the prime minister.

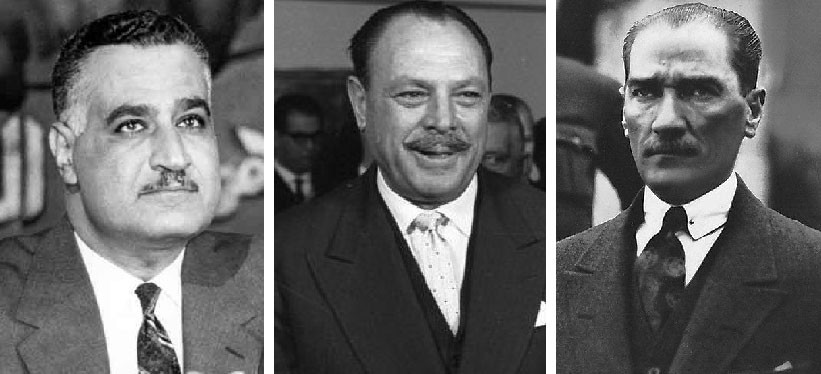

In Egypt, the army had already taken over in 1952 under the leadership of General Naguib who was removed by Gamal Abdel Nasser in 1954. He continued with one-party rule till his death in 1970. One common feature between the Turkish and the Egyptian armies during that period was their claim to be secular and opposed to religious extremism but if we look closely we find that it is the unquestioned army supremacy that engenders religious extremism.

In Egypt, Gamal Abdel Nasser tried to establish a modern state on more or less a similar pattern and had also emerged as a well-respected leader of the Non-Aligned Movement. While the armies in Turkey and Pakistan were ready to side with the United States in 1950s and 60s, Egypt initially kept a distance from the USA but eventually followed in the footsteps of the Turkish and Pakistani armies.

In Turkey, the army used Greece as a permanent threat and in Egypt and Pakistan, Israel and India served the same purpose. In each country, the generals became self-appointed custodians of national interest crushing the democratic aspirations of people and propagating the perception that only they were the true guarantors of security.

Just as in Turkey, 1950s in Pakistan marked an experimental period for democracy and multi-party system. In Turkey the first civilian president, Cêlal Bayar, and Prime Minister Adnan Mederes, angered the army by taking some bold steps without their consent.

In Pakistan, the army took over directly for the first time in 1958. Prior to that there were leaders such as AK Fazlul Haq, HS Suhrawardy, Abdul Ghaffar Khan, Ghaus Bhukhsh Bizinjo, GM Sayed, and Mian Iftikharuddin who could have steered the country on a democratic route, had they not been targeted and humiliated by the representatives of civil and military bureaucracy e.g. Ghulam Mohammad, Iskandar Mirza and Ayub Khan. But just as in Turkey and Egypt, in Pakistan the democratic path was abandoned altogether or realigned to suit the security establishment.

Nasser, Ayub, and Gürsel consolidated the military control in their respective countries and used the same mantra against democracy i.e. it promotes anarchy, threatens national integrity, and hampers development. In addition, it was claimed that the army brings everyone on the ‘same page’ to safeguard the country against unscrupulous elements.

In 1960, General Gürsel not only toppled a democratically elected government but also paved the way for the death sentences to both the president and the prime minister i.e. Cêlal Bayar and Adnan Mederes. Bayar was later on spared thanks to his old age and his sentence was commuted to life-imprisonment but Menderes was hanged. Nearly 20 years after this hanging, when in Pakistan the military government of General Zia was about to hang former prime minister ZA Bhutto, the then prime minister of Turkey, Bülent Ecevit, had reportedly remarked that Turkey was still paying the price for hanging its leader and he did not want Pakistan to repeat the mistake.

The Turkish army ostensibly restored democracy in 1961 but General Gürsel got himself elected as president. In a similar fashion, the military government in Pakistan established a civilian government in 1962 but General Ayub Khan followed in the footsteps of General Gürsel and became an ‘elected’ president.

Almost the entire decade of 1960s saw Nasser, Ayub, and Gürsel entrenched in their yearning for an ordered polity. Only Nasser among them enjoyed popular support till his death in 1970; while Generals Ayub and Gürsel could not present even a semblance of popular support or harmony that they claimed to have ushered in after the supposed failure of the elected civilian rulers. In Turkey Süleyman Demirel and Bülent Ecevit, and in Pakistan Mujibur Rahman and ZA Bhutto emerged as leaders espousing popular aspirations.

In 1970-71, the three countries saw events that had far-reaching implications. Nasser died in 1970 leaving behind a legacy different from those of his contemporaries in Pakistan and Turkey. Nasser had uprooted the kingdom in Egypt with his comrade General Naguib in 1952; then removed Naguib in 1954, first becoming prime minister and then giving a one-party constitution to assume the charge of president in 1956. Though General Naguib lived till 1984, his political role had finished 30 years earlier. When Ayub and Gürsel had offered their services to the US, Nasser had adopted an anti-imperialist posture and nationalised the Suez Canal inviting the wrath of Britain, France and Israel.

Gürsel had died in 1966 leaving Turkey in a mess again. This is no more a secret that from 1966 to 1970 the CIA was behind the unrest in Turkey and masterminding terrorist attacks to blame the leftist parties. Demirel was a centre-right politician but was not an extremist, still the army was not happy with him. In March 1971, when General Yahya Khan was about to launch his military operation against the majority party in East Pakistan, the Turkish army was writing a threatening letter to Demirel accusing him of incompetence and inability to control the law and order situation. The Turkish army had openly hinted at another coup repeating the same accusations against the civilian government that "it was destroying the country" and that politician were unable to come to the ‘same page’.

Almost the same situation was in Pakistan where the army did not want to hand over power to the elected representatives of the people because the politicians were ‘traitors’ and trying to disintegrate the country, hence they could not be entrusted power to rule on their own.

Anwar Sadat took over in Egypt after the death of Nasser in 1970 and continued with one-party rule under military supremacy. He ruled for over 10 years, fought a war against Israel and ultimately signed a peace deal brokered by the US President Carter at Camp David. Religious parties were enraged, especially Ikhwanul Muslimeen that attacked and killed him during an army parade in 1981.

To read the second part of this article, click here.