Pakistan has never developed into a nation where free speech is valued. The result has been a great dearth of new thinking and thinkers

"True, This! -- Beneath the rule of men entirely great.

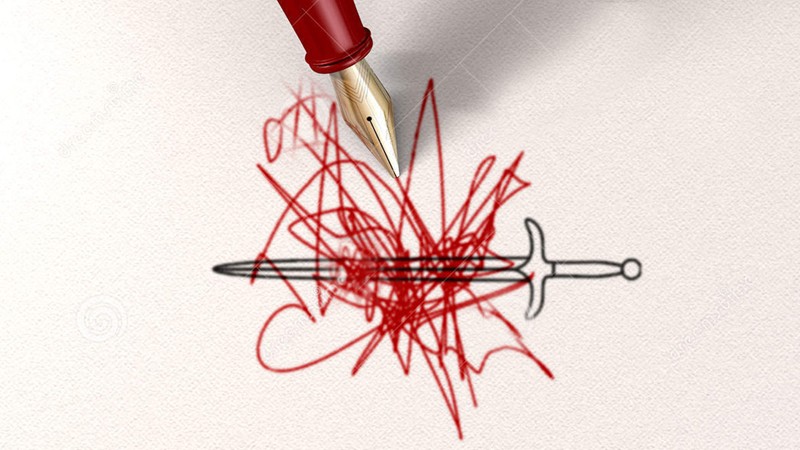

The pen is mightier than the sword.

Behold. The arch-enchanters wand! -- itself is nothing! --

But taking sorcery from the master-hand; To paralyse the Cæsars, and to strike The loud earth breathless! --

Take away the sword -- States can be saved without it!", said the famous Cardinal Richelieu in Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s play in 1839.

In the above lines the Cardinal, who was known to be the best diplomat of his times, argued that states can be saved without the sword -- the sword is only used by the weak. The power of the written word -- the pen -- if used skillfully is much stronger and more lethal than the naked sword.

In Pakistan, the powers that are fully agree with the Cardinal and, therefore, want to limit the work of the pen as much as possible. Since its inception, Pakistan has had an uneasy relationship with the written word. The first speech of the father of the country, Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah, to the Constituent Assembly was censored by the government, and in December 1947 the education minister was of the opinion that history was too important to be written by the historians and needed to become a government preserve.

With these attitudes as foundation, Pakistan has never developed into a nation where free speech is valued and where open discussion of subjects, however controversial, is nurtured. The result has been a great dearth of new thinking and thinkers in the country.

I once asked my students to tell me the name of ‘thinkers’ in Pakistan and they could mainly point out Allama Sir Muhammad Iqbal -- someone who had died a decade before the creation of the country. Forced to limit their answers to post-partition, they could muster up only a few decent names, with hardly any known beyond the confines of our own borders. With the limit of people born after 1947 only (and remember we are nearly 68 years old!) they could come up with no names at all -- let alone mediocre names. Such is the brain deficit in our country, and it is only getting worse.

A few weeks ago, I was personally handed over the directive of the Higher Education Department [HED] of the government of the Punjab that they were concerned that ‘anti-Pakistani’ and ‘anti-cultural’ topics were given for research to students in universities in the Punjab. Aside from the fact that with the creation of the Punjab Higher Education Commission under the sensible scholar Dr Nizamuddin, the regulation of universities is now under the purview of this Commission rather than the HED, I was rather amused to hear that there was research going on in the universities in the Punjab in the humanities and social sciences of such a calibre that the authorities were getting worried.

From my experience, and in conversation with other scholars, I have gathered that about two thirds of scholarship in the humanities and social sciences in Pakistan (especially history, which is my domain) is not worth the paper it is being written on. The other one third is very carefully written so that nothing much is said, and what is said is also mostly in agreement with the authorities of the day. So it is rather fascinating to note that there is something being written which is as daring and insidious as the HED letter is insinuating.

The pen can be indeed mightier than the sword but only when it is utilised in the proper manner. Wordiness and being without substance is worthless and such research is better not done. Pakistan now has a good measure of universities, but hardly an adequate number of scholars to support it.

While quite a few universities are now well-equipped in science disciplines, social sciences and humanities still suffer from a stark dearth of scholars and researchers. For example, all the history professors of all the universities in Lahore would not compare well with even a medium sized and mid ranked history department in a university in the United States. The reality of other subjects like philosophy and anthropology is much worse.

Therefore what we now need to focus on is quality not quantity. The government and especially the HEC and the PHEC should now stop setting up and recognizing new universities and aim to strength the existing ones first. They need to endow existing universities, create centres of excellence in them and support faculty research. On the side of the faculty, they need to move away from mere description to actual analysis, from rhetoric to evidence based arguments, so that one day when we again receive a ridiculous directive at least we can say that real research is taking place and that this is a move to stifle such endeavours.