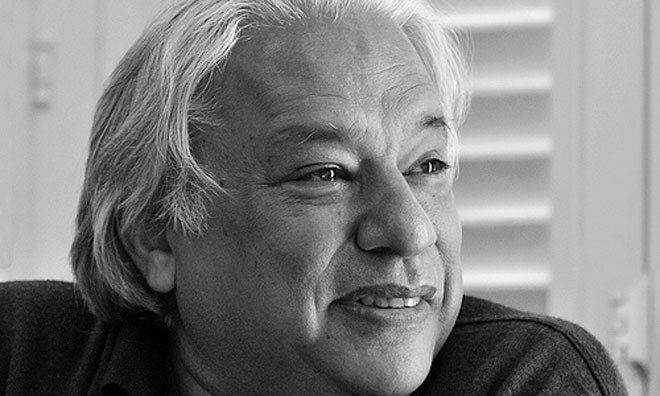

Arif Hasan, architect, planner, social activist, points to social and political changes taking place in Pakistan and why the state does not consider these when making policy

The News on Sunday: (TNS) Do you think that having lost its sole monopoly over violence, the state of Pakistan needs to redefine itself?

Arif Hasan (AH): It is a wrong question implying that the state is justified in having a monopoly over violence. Why should it have such a monopoly? State can adopt violence only when there is epic impediment to the execution of the functions of the state, or if violence is necessary in generating peace against those who are disruptive and when all courses of negotiations and peaceful resolutions fail. Some states are oppressive. They should be overthrown.

TNS: Has the state of Pakistan come to a point where it needs to lay down new goals for the country? Does the national interest need to be redefined and how? Do we need a new social contract?

AH: Pakistan is no longer what it was 25 years ago. There have been huge social, political changes. And these are not considered when dealing with policy.

There has been an eclipse of feudalism. Led by the collapse of the local system of commerce, governance, the panchayats, the jirgas, the patels, the numberdaars. They are no longer present. Moreover, the state has not tried to fill this gap. As a result of this change, many things have happened.

In the rural areas, the link between caste and profession has broken. The village artisans who provided services through barter system today work in cash. They have migrated to urban areas. The rural areas are entirely dependent on the urban produced goods. That is a very big change.

Another change is mobility. People move all over for trade and commerce. Where once roads used to be empty, today they are full of trucks. The Anjuman-e-Tajiran in various cities/towns has become an important political player. They are in constant negotiation with the state.

Women have emerged out of nowhere in public life. This trend is rapidly increasing. They dominate the public sector universities. Gender roles have changed. Extended family is disappearing.

All these changes require new society values and new governance structures, so that they can be consolidated.

TNS: What has led to these changes?

AH: All the reasons described above. Our population has increased 600 per cent since independence. There is technology/invention, cash has replaced barter, there are new varieties of seeds, farm sizes have become smaller, and the landless village labourer cannot afford the village’s dependency on urban produce.

Since 2000, over twenty universities have been established in small towns of Pakistan. Those who are studying in these universities are men and women from surrounding areas and villages. We have more people who are educated now. TV has also contributed in changing the values. Court marriages have increased. Migration abroad has also contributed to change in values. According to our study, migration and remittances have caused the breakdown of the family system.

All these factors have contributed to this change. Furthermore, you cannot close a country off from changes that are taking place all over the world. All these factors may lead to turmoil unless we can support them.

Also read: "On its own, no military can deal with political problems" -- Ejaz Haider

TNS: The failure of the state is often pitched against a functioning society. Do you see the two at variance with each other or connected since we also witness a deeply conservative and overly patriotic society which could only be a product of the state?

AH: We have a conservative and patriotic state with an ideology and a value system. But trends in society are unconsciously changing. And this change is unconsciously challenging the traditional value system.

Our so-called Islamic values are being violated all the time. We see roadblocks (protests) against injustices and women are active in these roadblocks; be they against karo-kari, excesses by the wadera, water shortage or anything.

These things were unheard of before. It shows that the society is fighting back. They are fighting back conservatism with contemporary values.

Media projects a lot of injustices against women, but they do not project the changes taking place, nor are they projecting the role models who are challenging these traditional barriers. Role models, too, are just individual cases, like Malala.

The problem is that not only the state, even the opinion makers and academia are not grasping these changes. They are constantly dealing with conditions, not with trends. Societal changes need to be understood, articulated and brought into consciousness. Right now, these are not being articulated at all.

TNS: How can they be articulated, when there is such limited space for dialogue?

AH: Who says there is no space for dialogue? Nobody is stopping people from reaching out. We are in a trap. We keep talking about jihad, cruelty of the state and society, and no doubt all this is there. We are talking about all this in the framework of nostalgia.

The past was a period of elitist politics. This is a period of populist politics. Karachi was the way it was because it was colonial port city being governed by colonial elites. Today, it is run by populist political parties.

The past was a very oppressive system, and it went on because people used to accept the oppression. Now there is freedom, most importantly, freedom to choose. The only thing is that people do not know what to do with this freedom.

Don’t miss: What must the state do?

TNS: To repeat a cliché, the institutional imbalance is said to have harmed Pakistani state. Do you think this institutional imbalance is on its way of course correction?

AH: The institutional imbalance has harmed Pakistan. This imbalance is located in the very foundation of this country, which has been a consistent actual and perceived threat from India. And India, too, has done everything possible to help with the development of this perception.

No, it is not on its way to course correction. Our political establishment is far too weak, corrupt and very much involved in seeing its class interests served.

TNS: Can you state a list of priorities for the state to make Karachi peaceful?

AH: The list would be: (i) A general depoliticisation of police, to whichever extent it is possible; (ii) Provision of housing for low-income groups. It is doable; (iii) The development of union councils as effective service providers. A Karaciite should not need to go to his religious or political organisation to get a birth or a death certificate done, or admit his mother to a hospital, or get a friend released from police custody. All this has to come under the purview of the union councils, and a Karachiite should have access to its secretariat. These measures would go a long way in making Karachi peaceful.

TNS: Is the constant migration in the city not a problem?

AH: Migration will keep happening. But the question is, are we prepared for it?

Right now 72 per cent of Karachi’s population is engaged in the informal sector. Karachi cannot survive that way. We need institutions to manage this. We need to have proper services for them, the industrial sector needs to be developed, you need to have a better organised services sector. We have minerals in the land around Karachi. Instead of giving this land to the Bahrias and the DHAs, this land should be turned into an agriculture zone which should provide for the city.

The most important requirement is good governance; a system that ensures that the needs of the people in such a large city are met.