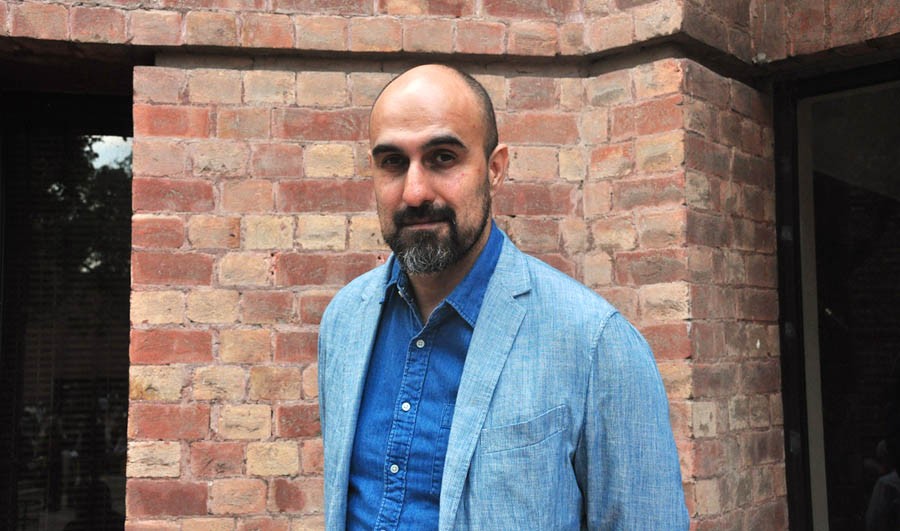

Hari Kunzru talks about his muse in this mechanised millennium, circumventing post-colonialism, identity issues and the UFOs

Hari Kunzru remains a seminal, albeit mysterious figure on the international literary/cultural landscape of this century. When all the secret histories of the century are finally told, his pivotal role as cultural border-crosser, psychic adventurer and aesthetic provocateur will have to be acknowledged. A foreigner everywhere, he has not claimed any one culture as his own. His sympathies lie most often with the outsider, whether in the guise of artist, immigrant or heretic. He recognises the advantages of his hybrid origins, so that whatever sparks of rebellion may be found in his work can be traced to his attitude towards the fixed thinking and implicit limits of all groups.

Born in London in 1969, to a Kashmiri Pandit father and a British Anglican Christian mother, Hari Mohan Nath Kunzru studied English at Wadham College at Oxford, and received an MA degree from the University of Warwick in Philosophy and Literature. After an exhaustive career as a journalist contributing to Wired UK, Guardian, Time Out and Wallpaper, he wrote his first novel, The Impressionist, followed by Transmission, My Revolutions and Gods Without Men, set in the American southwest -- the last often compared to David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas. Winner of Betty Trask Award and Somerset Maugham Award and several others, his importance as a writer and theorist continually perches on the razor’s edge of innovation.

On the occasion of LLF 2015, he spoke of his muse in this mechanised millennium with aplomb and patience, circumventing post-colonialism, identity issues and the UFOs.

Excerpts follow:

The News on Sunday: You believe a writer doesn’t write so much with ideas as with obsessions. How did this ‘journey of obsessions’ begin?

Hari Kunzru: I sometimes say it was because of a lack of imagination! I started to take my writing seriously during my last year as a university student, when I was twenty years old. I was a great admirer of fiction writers, and as a young man, I had had such extraordinary experiences as a reader that I could have thought of nothing better to do with my life than become a writer. So, I ignored all the practicalities and started writing a novel when I left the university. It was a bad novel; it wasn’t planned properly, and I made many mistakes. I had spent two years doing odd jobs to feed my mouth; made this work that I sent off to agents and was rejected, but I was told by one agent that I had talent and that I should try again. That was enough for me to feel that I could go on.

Until the rest of my twenties, I took up all sorts of work, gradually began to work as a journalist to support myself, and carried on with my writing. Finally, when I was thirty, I produced my first novel and got the book contract. Since then, I’ve been able to support myself mainly by writing fiction.

Most of the people among my friends didn’t know I was writing fiction -- they knew me as an internet journalist. It was quite a surprise for them that the first book I published was a historically set novel -- they would have expected me to write about the future while I was writing about the 1920s Raj.

I have never loved the short story the way I’ve loved the novel. A book of short stories did not precede my first novel. In the UK, you are definitely encouraged to try to write a novel because there’s no market for a book of short stories. In the US, on the contrary, there’s a whole culture of selling short stories. Often young people come out with a collection first but with British writers, you wouldn’t get the chance of publishing a book if it was short stories. (I was writing ‘at length’ from the start). That situation persists even today. You will find that British writers tend to have a novel as their first publication, and the American ones, especially those who come through an MFA Programme, have stories. They were making these short books for Penguin’s 70th Anniversary, and I made not even a full-length collection but a tiny book with five stories in it. So far, that’s the only collection of stories I have published.

TNS: What made you turn to journalism, especially travel writing?

HK: These were all pragmatic kind of decisions. My career as a travel writer was not a considered one. I discovered people who would buy me air tickets if I wrote them a couple of thousand words about what happened to me. In my twenties, I made a connection with the travel editor of Time Out -- he would send me to various places. He was not taking more than four or five pieces. I was able to go to Benin in West Africa and attend Voodoo rites as part of the research for my first novel. (I would often try to have an ulterior motive in my travels).

As far as Kashmir is concerned, it’s something I’ve always turned over in my mind. I was in Kashmir once when I was sixteen, when insurgency was beginning to take off after which it became really difficult to travel there. We visited the ancestral village of Kunzergaon not too far away from Srinagar. At that time, there was still a pandit in Multan who kept the family genealogy intact that he recited to us. One of my cousins who is a filmmaker had been back there recently. He said that the temple is gone and the pandits are scattered completely. In other words, I’ve lost the few connections I had with the valley. My family left Kashmir in the very early part of 19th century. Their migrant community is around Agra, Lucknow and Kanpur. Later they seeped into Jaipur and the rest of Rajasthan. I’ve heard among some circles that there are Punjabi Pandits who don’t speak Kashmiri anymore.

I’ve thought about constructing a novel about Kashmir but felt very under qualified to do it. There are people like Mirza Waheed who have got much greater depth of knowledge about the culture of the valley, and have much stronger connections with it. I haven’t ruled out the possibility but I have to travel there. I was talking to Basharat Peer about both of us going there -- one as a Kashmiri Muslim, the other as a Kashmiri Pandit.

TNS: You have always been a champion of novelistic objectivity, because you despise thesis novels. Yet, you ended up revealing your autobiography in The Impressionist.

HK: That was my way of trying to understand my roots because I grew up in the UK. And the reason why I grew up in the UK is because of the colonial connection between England and India. My father had taken the decision to come to work in Britain as a doctor. He did that because Britain was a ‘natural’ place for an ambitious young Indian to travel to. I grew up with the question that a lot of white people in the neighbourhood would ask: "Where are you from?" I would say, from Essex -- which was name of a place in the suburbs. They would go: "No, where are you really from?" I would find that a troubling question because it seemed to imply that in some way, I was not where I felt I was from. I grew up all my life in a London suburb.

As a teenager, I really pushed that at the back of my mind because I wanted to be the same as everybody else, and I didn’t want to emphasise my difference, my Indian origin. I did assimilate but I also became angry about some of the ways I’d been cheated. I became proud and interested in the desi side of my being as I became older and more comfortable. I wanted to write something that was set during the Raj because growing up in the 1980s in the UK, the dominant images of Indo-Pakistan were the Merchant-Ivory films with neatly dressed colonial masters and silent servants. I found them insulting and hated them. I didn’t want to see them carry a tray with a lime soda on it. All this kind of fantasy of mastery, of the colonial past. What I wanted to do was to satirise that ruthlessly. I went into the question of race and hierarchy, the white authenticity versus the brown authenticity because I am neither white enough nor brown. This is the basic fact of my life.

I’ll never be a proper Indian and I’ll never be a proper Brit. I am inauthentic, and I wanted to write for all the other inauthentic people -- somehow in praise of my own inauthenticity.

TNS: There’s a huge transformation of character in the protagonist’s personality in your first book. Where, do you think, his sense of identity came from?

HK: This is the central question of the book. My fear was that I was not authentically anything. Somehow, I was just a product of chance and of circumstance that I happened to have been in. My question to myself was: "If you don’t have a solid interior sense of yourself, and you decide to change everything about your location, do you become a different person?" I wanted to see what the limits of change are for a human being.

So I made this character who has a lot of self-hatred and self-disgust, and has very little to hold on to when his situation changes. Is he substantially the same person when he is pretty Bobby in tin tin Bombay? Is he the same when he’s pretending to be Jonathan…? He has a hole in the middle. He is a creature of surfaces, as I say somewhere in the novel. It becomes a wider issue for me when it’s about identity and authenticity, or about how much of us is constructed by our circumstances. In a way, there is something melancholic about his ruthlessness but also something skilful about his transformations -- the side I wanted to portray!

The protagonist’s tragedy is that he’s always trying to assimilate fully. He’ll go to incredible lengths to become ‘something’ in the hope that that will fill him up. And he never does; instead, he moves on and on and things become less and less clear. As a man in my forties, I am now comfortable in being cosmopolitan, in the fact that I am a product of these different influences even when I am not completely any one of them.

Honestly, the change for me was in my early twenties when I began not to try to fill roles, and not try fully to inhabit some silhouette that I was seeing in the media or in some other person I admire.

TNS: Has there been an attempt to justify the colonial presence in the East by creating a context where the locals are being seen not merely as subjects but also as sycophants, in your novel?

HK: Empires have always needed local collaborators, and elites have, in every place, benefited from participation. I quite understand the sense of shame that comes of being colonised; the sense of rage that not more was done to retain autonomy. But, at the same time, some tools come to you and English proved to be a useful tool in the subcontinent. For very obvious political reasons, English carried on -- Hindi and Urdu would have been a problem for the South. A pragmatic decision was to be taken that English would carry on being the medium in which a lot of business was conducted. As it turned out, it’s now become a sort of international property. Of course, that gives a certain advantage to those of us who are native speakers of English.

But the language brings with it a mindset that the current Indian government finds very distasteful. For instance, attempts to eradicate that aspect of history are underway, and distaste for the English-speaking elite is part of the politics of Modi government in India. We can’t turn the clock back. The rule for a former colony is: if it’s useful, keep it; if it’s not, don’t!

TNS: Technology and mechanism have had a major role to play in your subsequent novel Transmission. Do you think spirituality is plagued or eclipsed by technological warfare?

HK: If there’s a ghost in every machine? People tend to see them as opposing poles: The tradition is to see the soul as machine and then the soulful spirit. But we put ourselves into the machine -- we are the builders, and they will become what we’ll put into them. If the only purpose of your machine is to dominate and control, that will come out. I think there is nothing intrinsically soulless about something just because it is a mechanism.

I am not saying there is no danger. There’s a very strong danger especially now with the kind of ubiquitous network computing that surrounds us, embedding of artificial intelligence into all sorts of objects. We are beginning to get to a stage where these mechanisms have some degree of autonomy. Let’s stop short of saying ‘intelligence’ or ‘artificial life’, they have a great deal of autonomy and they are getting more so. We are all going to be confronted by this ethical question about machines with agency, machines with autonomy, machines that are given very serious powers to. I was talking about guns that can choose targets without human intervention. That, in many ways, contradicts what I was saying before that they are only what we put in but I still believe that when we make mechanisms, we have to ask ourselves these ethical questions. What machines we choose to make -- that’s a very thorny and complicated area.

TNS: In your last novel, Gods Without Men, what made you move to Mojave Desert?

HK: I’ve always been drawn to desert. I’ve always experienced a great rush of energy being in a desert. I also wanted to write about America -- I’d actually moved there intending to write something on New York or something completely different. And ended up realising that I had to take up America as my theme. I needed to escape from the city, and the verticality of the city. (I often joke that it’s all about the verticals and the horizontals). New York is all about verticals and Mojave is a huge horizontal plane.

I don’t think of a theme and then decide to write a novel about it. Something snags, and it attracts other material. At a time, I was without a project and was very worried about that. I was concerned that I might be having writer’s block. So I accepted an invitation from some friends to go on a little road trip with them from Los Angeles out into the desert. There was a couple having some problem in their marriage. So I was refereeing this couple as we drove to the desert and stayed in cheap motels. I decided to write a short story about a couple having a fight in a motel. That was the beginning of a much larger and wider project.

I made a rule that I would not try and plan the whole novel, that I would set to explore in an intuitive way, and that part of the US is where UFO mythology came from. UFOs are very present in people’s conversation, and they talk about seeing them. It became clear that the book in some way is going to be about spirituality, about a sense of the divine come down -- that tradition of revelation in the desert in various villages, and the UFOs began to map on to that.

The first generation of people who claimed to have been contacted by the UFOs or who’d seen them had a background in Theosophy and spiritualism. There’s a direct link between the 19th century occult and the UFOs.