Fawzia Mirza’s one-woman act was the piece de resistance of NAPA’s International Theatre Festival

Some actors hold an audience, a few possess it. Some actors light up a scene, a few ignite it. Ms Fawzia Mirza, the Pak-American actress, belongs to the latter category. Her one-woman act, Me, My Mom and Sharmila, which she staged at NAPA’s recent International Theatre Festival was, in the jargon of Variety, (the American showbiz newspaper) a Win Win Win.

In all the years that I have been watching plays and players I have not come across any actress from our subcontinent who has shown such self-assurance and theatrical ability in bringing to life characters that Fawzia Mirza portrayed, even though as caricatures.

Aided by Brian Golden, she has written a play -- monologue to be precise -- which was concise and razor-sharp, interspersed with an adroit mixture of humour and pathos. It was precisely the right length. A twitch more and it would have become maudlin. She played it totally and absolutely, never flagging for a moment. Her timing was spot-on and the energy she exuded was electrifying. Her pace never slackened. What she executed, with panache, was life as a performance.

About herself Ms Mirza has written "…I love to use performance, personal story-letting and comedy to break down stereotypes across a multiplicity of identities, race, religion, sexual orientation and gender and defy the concept of ‘model minority’ often portrayed in the mainstream."

To hold an audience for an hour and a half, single-handedly, is a tough nut to crack for any actor. You have to speak trippingly on the tongue, your pace has to be crisp, your diction has to be faultless, but these are ingredients which you need to possess when you play any sizeable part in the theatre. For a monologue, to be riveting, your material has to engage the audience from the moment you begin to speak. And this she managed with enviable elan.

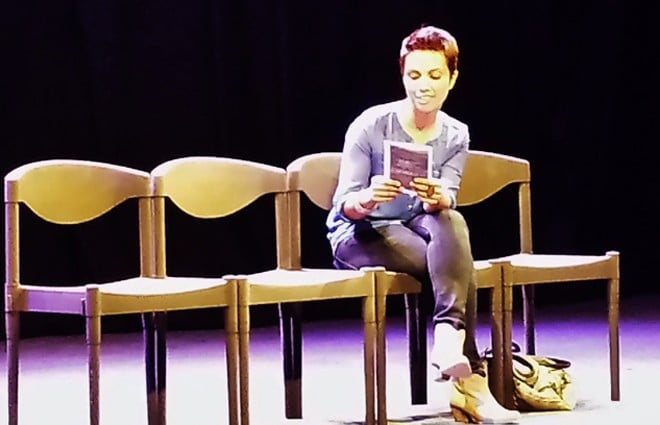

On a bare stage with no other props or scenery except four armless chairs in a row, she begins her journey of self-discovery. As a Muslim child of Pakistani parentage she grows up in a small town in Canada, then in a big city in the United States. During her adolescence she has a crush on an Indian movie-star, Sharmila Tagore, who becomes the goddess of her idolatry. (Sharmila is the metaphor around which she spins the web of her narrative). Skilfully, she traverses three oceans, the subcontinent, North America, and that deepest of all oceans; loneliness of the soul.

Now and then there is a winning flash of a grin, crooked and raffish, accompanied by an upward flick of the eyebrows followed by a pregnant pause. It drives the point home. Ms Mirza has artfully adopted the American stand-up comedians’ manner of nodding her head to suggest "You may think that what I have just said is blarney, but it is a fact, like it or not." With another grin, which I can only describe as wicked simplicity, she makes her barbed asides.

In between her narrative there were two beautiful vignettes: her rendering of a nursery rhyme about the antics of a chick, which she learnt as a child, and her mother’s transformation from a fashionably-attired socialite to a religious, hijab-wearing woman, guilt-ridden about her floundering past.

The mother leaves the United States to go back to Pakistan. The chasm between mother and daughter deepens. The daughter now lives in Chicago struggling hard to make a career as a writer-performer. Men are not a part of her life. She realises that she can have a meaningful relationship only with a member of her own sex.

The episode in which she tries to tell her mother, over the telephone, that the girl friend she lived with was not a companion, that she herself is, in fact, a… but she cannot say the word lesbian. The pause that follows, during which Fawzia Mirza simulates her mother’s wordless reaction, her mouth agape and aghast at the shock, horror and guilt of having spawned such a degenerate daughter was tour de force.

Towards the end, after a pause, as a respite from unassuageable melancholy, she makes one final attempt to reach out to her mother. She rings her up and, to humour her, begins to recite the ‘chick’ song (which her mother always coaxed her to sing when guests were around) but anguish takes over. Her voice, now a whinny, she realises that she will never be able to connect with her mother again. It was a moment of ineffable sadness and a moving end that brought a lump to my throat.

One of the critics who reviewed ‘Me, My Mom…’ wrote, "One feels that a little bit of visual aid, for example a film projected image of Sharmila or film footage could compliment the script well, and might even enhance its impact."

I disagree entirely. Had it happened, it would have sentimentalised the narrative and diminished its impact. Theatre is the art of the actor. What the actor can achieve with his voice must not be tampered with visual and mechanical aids.

As an illustration. I refer to a paragraph on the last page of Samuel Beckett’s novel HOW IT IS:

"…alone in the mud yes the dark yes someone hears me no one hears me no murmuring sometimes yes but at other times yes when the panting stops yes but at other times no in the mud yes to the mind yes my voice yes mine yes not another’s no mine alone yes sure yes when the panting stops yes on and off yes a few words yes a few scraps yes that no one hears no but less and less no answer LESS AND LESS yes…."

It all sounds like gibberish or a staccato tirade, but a seasoned actor can punctuate the speech into lucidly with his voice and the change of his inflections. If you project images of a barren landscape along with amplification of eerie sounds you will be pampering the actor. How well I remember that highly individualistic actor, Nicole Williamson, who gave Beckett’s monologue a hypnotic quality. The voice that he used was that of a man in his last extremity, living on the very margin of existence.

Who but the actor has the ability to transform the commonplace making gods of men and men of gods? Lawrence Kitchen summed it up succinctly: "Although the traffic in entertainment can lead one to forget it, the actor is one of nature’s miracles. He brings aspects of music, poetry, literature and sculpture within the capacity of a human being and transmits it to a crowd."

He was, of course, talking of actors who ignite the stage. Ms Mirza’s one-woman act was the piece de resistance of NAPA’s International Theatre Festival of 2015.