Free speech is an extremely difficult subject in Pakistan. And things do not become any easier with the speed at which modern communications technology, including social media, has grown. We now live in the digital age and this forces us to re-examine our conventional view of things.

The digital age takes a life of its own and raises serious concerns about privacy, online speech and associated state action. Let me make something very clear at the outset: I am not calling for a repeal of any legislation in Pakistan. I also think that it is extremely unfair, as well as naïve, on the part of human rights groups to call upon politicians to repeal legislation that NGOs deem unfair -- such as the law on blasphemy.

Those who have to go to their constituents and ask for votes cannot be expected to ignore popular passions. What they can, and should, be expected to do is to build in proper safeguards against the abuse of the law. The necessity for prevention against miscarriages of justice is something that everyone can and does agree on: including the religious right.

This then results in a change from the conventional approach: we need to stop thinking that Pakistan has a ‘blasphemy law’ or ‘invasion of privacy’ related problem. And we need to see Pakistan as having a ‘rule of law’ problem -- the entire system needs huge improvements to ensure proper investigation, protection of witnesses, procedures being followed at trial, equality of arms, due process etc. And this goes for all offences.

The solution that you then design and/or recommend to guard against miscarriages of justice will factor in the whole system and will not commit the mistake of imagining that one particular criminal offence exists in a vacuum. This is particularly important for the donor community to think about.

If you cannot solve a particular problem, there probably is good reason for it. The solution? Re-imagine the problem.

And if you think that a particular offence being on the statute book offends you then remember that politics is the art of the possible. So, can you get enough votes to change a law you do not like? Is it even practical to expect a politician to go, hat in hand, asking for votes regarding repeal of that law? And if the answer is no, then you can advocate the building in of checks and balances to guard against abuse of the law you find offensive.

The UK as well as many American states have (or had) laws on their books which fell into disuse. Proper procedures and prosecutorial independence can go a long way towards guarding against abuses of any penal provision.

Many NGOs in Pakistan have shown their justifiable concern at the state’s handling/censorship of online speech. However, the solutions that most of them often propose require an "all or nothing" approach -- they want a world in which laws deemed offensive do not exist. In a country as difficult to manage as Pakistan, this is ill advised.

As Amartya Sen argues, one way of ensuring justice in a society is to reduce injustice. Creation of a perfectly just society is not the only measure available. Therefore, such "all or nothing" approaches not only make the task of the legislators more difficult, they also fail as solutions that can be ‘sold’ to the masses.

Yet another problem is the obsession in Pakistan of demanding new laws to govern us in the digital age. Cyber bullying and cyber harassment are of course serious problems. So are accounts that spread hate speech. But instead of using existing laws to cover such actions, many in the NGO community called on the government to enact a new law. And with the Draft cyber-crime legislation now doing the rounds, freedom is definitely not getting a thumbs-up.

A state will not forego any chance to increase its power. And by continuously calling on a state as broken as Pakistan to come up with new laws, we are not increasing freedom. We, perhaps, might be better off tweaking existing laws and systems in our search for a more ‘just’ society.

Every time we demand the state to take action to ban any content online, it will use this opportunity to increase its power in future to block content it does not want you to see. When liberals in this country ask for any online content to be blocked or banned, they are doing the state a favour. The best solution is perhaps more speech -- whether it takes the form of protest or advocacy. That is how discourse is shaped.

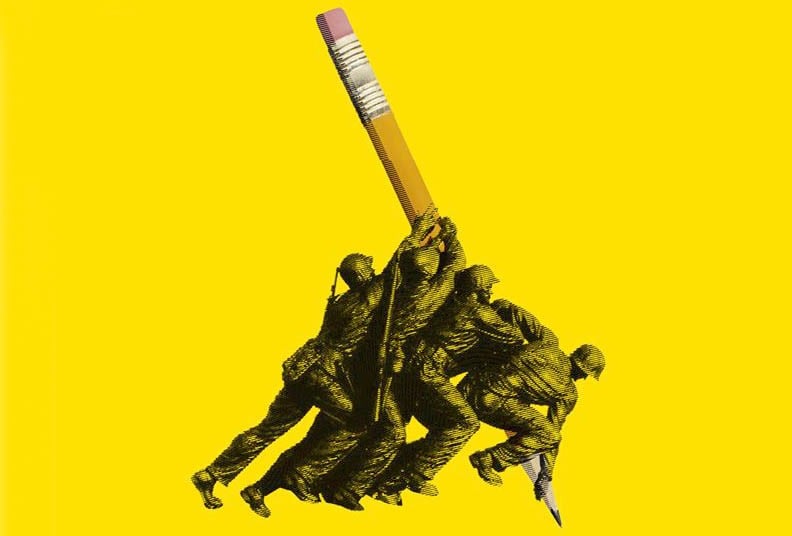

The digital age reminds us, more than ever, that freedom of speech is in peril in Pakistan -- and indeed in most countries in the world. The state will keep coming up with different excuses to block or ban content. Our job in this struggle is to push for more, and not selective, speech.

And as far as reforming the criminal justice system, and its abuses, is concerned it is high time we take a holistic view of the problem rather than a disjointed and, worse, impractical approach.