Better education will remain a dream unless qualitative aspects are given more importance than quantitative ones

In Pakistan, education research suffers, inter alia, from two major maladies. One, lack of credible data, and two, lack of capacity to analyse quantitative and qualitative data to draw sound conclusions and make recommendations. Most research studies use the data from government sources, for NGOs and other independent research outfits simply cannot shoulder the burden of data collection in a country of around 190 million people where almost half of them are in the age bracket that should ideally be pursuing some education at school or at tertiary levels.

The data sets maintained at the governmental levels are mostly quantitative by design because it is easier to show performance in numbers and much more difficult to demonstrate how quantitative changes are resulting in some qualitative changes, if at all. Recently, donors have supported a substantial number of private entities and non-governmental organisation in the collection and analysis of education data, but sadly the quality of research produced by most -- barring a few -- organisations is questionable.

The recently released report on public financing of education in Pakistan by the Institute of Social and Policy Sciences (I-Saps) is a welcome addition to credible education research in the country. It analyses the data of public education financing for a five-year period from 2010 to 2015 mostly at the federal and provincial levels by comparing and contrasting. Probably, it is the first attempt in the education history of Pakistan to have such a broad scope and present a picture that is both objective and convincing.

Since after the 18th Amendment the Federal Education Ministry is largely concerned with the higher education across the country and with school education only at the federal level, the provincial budgets are the real game-changer in school education. In terms of percentage increase on yearly basis Balochistan has shown a better performance; in 2013-14 it had allocated 18 per cent of the total provincial budget on education and then increased it to 19 per cent in 2014-15, showing a betterment of one per cent. This might not look impressive but if you compare it with the three per cent decline in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa from 29 per cent to 26 per cent, Balochistan does not fail to impress, while Punjab and Sindh have shown two and three per cent decline respectively.

In terms of sheer numbers too, Balochistan leads the way by posting a 17 per cent increase from Rs35b to Rs41b in one year while Punjab comes second with a 12 per cent increase and KP and Sindh show 11 and 10 per cent increase respectively. Punjab and Balochistan have also shown the best performance in terms of development budget in education by increasing it 22 and 20 per cent in that order. The share of development budgets in education shows a remarkable decline of 12 and 13 per cent in Sindh and KP respectively.

For the uninitiated in public education financing, it might be helpful to mention that usually the current budget includes allocation and expenditure on goods and services consumed within the current year and subsumes recurrent costs of a spending unit. So the salary and non-salary budgets both come under the head of current budget but the development budget -- that earmarks allocation and expenditure on development activities and schemes such as infrastructure and capacity development initiatives with a finite life -- is usually presented separate from the current budget.

Interestingly, while the salary component of the current budget is invariably consumed in full, the non-salary component that covers other than employees related expenses such as operating costs, purchase of physical assets, repairs and maintenance, shows large chunks of unspent money. Sindh has the dishonour of not spending as much as 53 per cent of the non-salary budget last year; KP occupies the ignominious second position by not spending 41 per cent of this head, while Balochistan and Punjab too retained 27 an 17 per cent unspent non-salary budget respectively.

The development budget that is so vital for improving the quality of education and learning environment remains the most neglected area in the three provinces other than Punjab. Again, Sindh has the dubious distinction of not spending 67 per cent of the development budget during the last fiscal year. KP and Balochistan education departments also demonstrated lack of interest in spending their development budgets by keeping 50 and 48 per cent of this component unspent. Only Punjab was better and managed to utilise 89 per cent of the money allocated for education development.

It is so disappointing to note that none of the four provinces could claim they had the capacity or willingness to make full use of development resources available to them. Normally, such negligence goes unpunished because the officials responsible for not spending the allocated budgets have readymade excuses up their sleeves, such as slow release of funds, strict government regulations for tendering and making contract-award process transparent. The more transparent the process becomes the less chances there are for corruption and even less is the desire in public officials to indulge in something that has reduced opportunities for personal benefit to them.

When the education departments fail to utilise development budgets, sometimes provincial governments use this as an excuse to reduce the development budget in the next fiscal citing lack of capacity as a major reason for such reduction; as happened in KP and Sindh that reduced their development budgets by 13 and 12 per cent respectively. Thus, if we look at the 2013-14 budgets, Sindh spent a paltry sum of around Rs5 billion on education development out of an allocated amount of approximately Rs17 billion. One wonders, if Senior Education Minister Nisar Khuhro would like to investigate the causes behind this underutilisation. Balochistan was slightly better that spent Rs5 billion out of Rs10 billion allocated for education development; but still deserves some investigation.

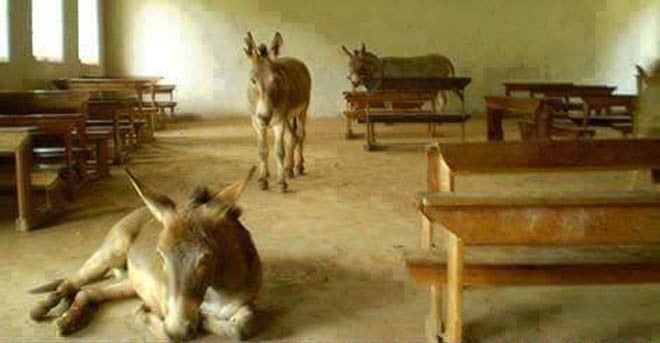

That is where the qualitative aspects become much more important than the quantitative ones. But before exploring the factors that contributed to the shortfall in spending, the first qualitative question that should be asked is related to what has been achieved with the development expenses already incurred. Quantitatively it can be ascertained by counting, let’s say, the number of new toilets built; but qualitatively a more pertinent question would be how many toilets are actually functional i.e. they have a supply of water and daily cleaning arrangements at regular intervals. It is a sad reality that a vast number of schools do not have toilets at all but even more disturbing is the fact that while more money is allocated for building new toilets, hardly a mechanism is in place for uninterrupted supply of water and regular cleaning.

Similarly, more qualitative questions should be investigated such as about development spending on capacity building -- a more impressive term for any run-of-the-mill training that every other NGO claims to specialise in. At a recent review of a donor-funded project, this scribe was shocked to see claims regarding thousands of teachers having developed their capacity in a five-day training that included Math, English, Science, and Computers. Those five days too were half-day events with frequent breaks for tea, samosas, lunch, and prayers, hardly leaving time for any worthwhile activity.

Even more surprising was the presence of teachers who had already attended similar events in the past, but through their connections got repeated opportunities of ‘capacity development’ at the donor’s expense. The donor representatives were more interested in being able to ‘burn’ the money, failing which they risked questioning by their bosses; contrastingly, no such probing was done regarding the quality of training or the competence of the trainers themselves or the contractors that mange such programmes.

Another important point highlighted by the I-Saps report is the education expenditure per student. While all the provinces have increased their expenditure per student in 2013-14, Sindh is the frontrunner with 21 per cent increase resulting in over Rs20,000 being spent per student in 2014 in comparison with Rs16,500 spent per student the previous year. KP was the second that increased per student expenditure by 17 per cent, taking it from Rs13,000 to over 15,300 in a year. Balochistan jumped by 16 per cent reaching the highest per student allocation of almost Rs22,000. Now again, the qualitative inquiry bothers me; one tends to question the RoI (return on investment) that must be better student learning outcomes.

The qualitative challenge is to find out what value addition is being made after spending almost Rs2000 a month per student. If we look at LFPs (low-fee private schools), the results in most cases are much better than the government schools. The qualitative answer probably lies in the kind of learning that is being imparted. In the seminar where the I-Saps report was launched, one of the education ministers revealed that a senior government school teacher is paid as much as Rs100,000 a month by the government. Now without any qualitative probing, it remains to be seen how a private school teacher who is paid less than ten per cent of the government salary, performs better and students in almost all independent tests display better learning outcomes. In terms of increase in per student expenditure, Punjab has remained relatively modest by marking just a three per cent increase from Rs15,200 to Rs15,700 in one year.

Now, looking at the federal budget highlights of 2014-15, the government is to spend Rs84 billion on education out of a total budget outlay of Rs4,300 billion. Nearly the entire federal education budget is to be consumed by higher education i.e. financing all the public sector universities, research institutions, and colleges in the federal territory. That leaves a minor portion for primary and secondary schools located in the ICT (Islamabad Capital Territory); and there too, there has been no allocation for education development at primary and secondary levels in 2013-14.

According to the I-Saps report, Pakistan’s education spending is still hovering around two per cent of the GDP, making it the lowest spender on education in the region. Despite repeated claims by successive governments, the completion rate has declined in the recent years and around one thirds of the pupils enrolled at the primary schools fail to survive and drop out before or immediately after completing their fifth grade.

In terms of literacy rate, every now and then an announcement is made to provide universal primary education in a decade or so; but, as the I-Saps report reconfirms, the current literacy rate is not more than 58 per cent that was supposed to have reached a least 88 per cent by 2015 as promised during the Musharraf regime.

In Pakistan, where for government teachers holidays are long, and the pension is gold-plated; it is about time we started asking qualitative questions. Teaching should not be a profession for mediocre timeservers. The quantitative barriers such a biometric attendance may sound innovative and generate a lot of data and may also prevent teachers from playing truant. But unless it is made easier to sack teachers who don’t improve qualitatively, they will simply be improving their own life prospects.

As long as lazy and incompetent teachers and officials can get away with slacking, there remains no motivation for hard-working ones. But, that applies only to those schools where there are teachers; if there are 58 per cent schools running with only one teacher in Balochistan, it might take another decade or so to rectify both quantitative and qualitative problems.

The I-Saps report is a milestone in the right direction, but, it mostly relies on the government financial management information system or PIFRA (Project to Improve Financial Reporting and Auditing). More primary research support is required for qualitative data analysis that may inform better policy decisions.