The novel suffers from a lack of focus -- slipping from feminist to a novel about transition to life under British rule to one about general suffering of people

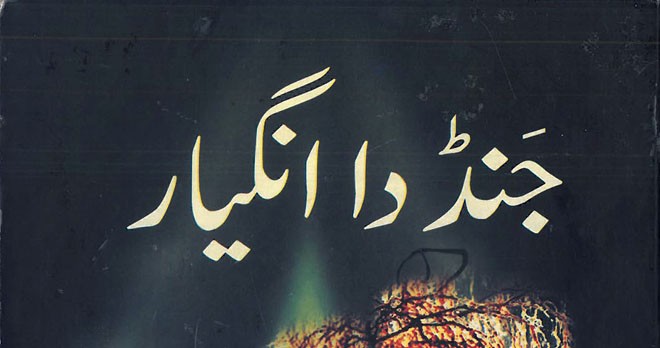

It is acknowledged that art results from the unconscious and in the process of refinement the artist engages with it consciously. It is, then, a dance of the two. Similarly, a fiction writer may not know why a certain idea gripped her, she must know during the process where the two are being led to. While the author learns the route of the novel, a skilful novelist makes sure the reader does not, lest the magic is gone. An author has many tricks up her sleeves to pull the reader by her nose. Farkhanda Lodhi’s strongest point in her solo Punjabi novel, Jand da Angyar, is the language and lack of inhibition.

The time is hard to pinpoint until the reader reaches the last part when Bhagat Singh Shaheed is mentioned before he’s hanged by the British. The reader can then travel back and make a guess. The British have taken the Punjab, subdued resistance, dug canals, shifted population and allotted land to those who supported them, and established bureaucracy. The protagonists draw a lineage from the great Ahmed Khan Kharral who valiantly stood up to the British and though the tide of rising imperialism washed over the warrior, his killing Lord Burkley became a source of pride for many Indians. The family has lived in the bar region for many generations.

It is a tragedy if the reader feels that the writer could not hold the novel’s centre or visualise its arc. Both feelings seem to mark the novel. The novel that started with life and the tensions that come with it ends up following characters aimlessly with a tendency for the melodramatic. The novel opens with an old man returning home with a young girl (cheaply purchased from some destitute family) as a future wife for his eldest son, Sharmaan whose younger brother Matheela ends up marrying his wife, Khattun (from Khatoon) when one morning he’s found dead in his sleep. Whether her first marriage remains unconsummated or she could not conceive, Khattun ends up having five sons and five daughter with Matheela. In a remarkable second chapter, Lodhi travels back in time and we learn of the short lived romance between Sharmaan and a childless married woman. As she disappears, Sharmaan is accused and destroyed in the process.

It takes the reader a while but the realisation sinks in that the author has no clue what the novel is trying to achieve. The chapters relate to the lives of a select few children and grandchildren. One of the sisters ends up selling her two daughters to a woman who lives in Lahore and runs a brothel. She is the daughter of the woman who had disappeared right under Sharmaan’s nose. It turns out a British bureaucrat had kidnapped her and turned her into a prostitute with the connivance of a native informant.

When one of the sons, Mahatam (play on mahatama?) leaves the insularity of his native village, he ends up in the service of a native police officer, who arranges a night of debauchery, it seems, only for Mahatam to recognise his own nieces. The rest of the novel is full of similar absurdities killing much of the nuance that could have saved the novel. Lodhi forcefully tries to impose a plot where not much is left to imagination.

The novel starts out with an interesting feminist note with the acquisition of a child bride without descending to dehumanising people. It tries to expose an aspect of our rural culture in a given time and space coloured by extreme poverty and patriarchal traditions. It also shows, as the lens moves onto an expanded territory, that far worse attitude towards women prevails among the ruling and educated classes. The author makes a connection that the behaviour of the ruling elite is far more damaging to the overall health of the society.

The novel suffers from a lack of focus -- slipping from feminist to a novel about transition to life under British rule to a general suffering of people. Mahatam emerges as the main character for the second half of the novel. Her lack of focus becomes obvious even when she is handling him. We are not sure what is driving him restless. Is it unrequited love? The search for his nieces? Genetic disorder? The political unrest? Awareness of his cultural roots?

The author tries to compensate too many elements without providing Mahatam any clear moral vision. Lodhi distributes the metaphor of jand da angyar too freely to her characters. The process is inorganic and it dies a death akin to Mahatam’s as a crowd which had come to watch a Ram Leela celebration smothers him in their panicky retreat. But in the process one of his nieces whom he had earlier rescued is crushed too. This is sloppy since this niece is the only female character with any sense of agency, and her careless death can symbolise the death of all female characters.

And it is all the more tragic since the author lured them to the festival for no logical compulsion. Both the uncle and the niece know that prolonging their stay in Lahore can land Mahatam in jail as his photo is splashed all over the city. To not allow characters that basic intelligence at a crucial point is a disservice. It is not the police that kill or capture him, but the unruly mob.

The novel that started on a compassionate note about the dispossessed ends up turning them into one monolithic, faceless demon. That’s a silly note to end the novel on.