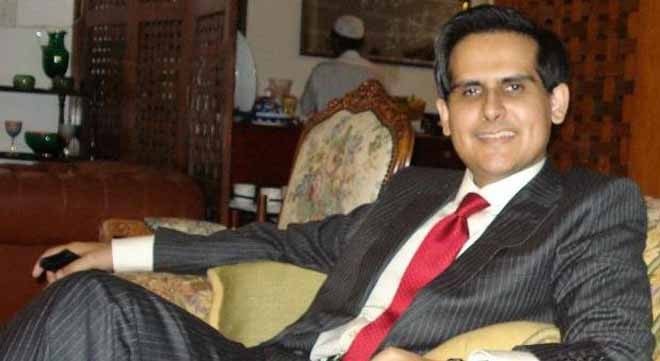

Ilhan Niaz talks to TNS about his recent book and issues related to the abysmal state of social sciences in our academia

A widely read young scholar with a vision that one rarely finds among the people of his age, Ilhan Niaz is the author of ‘Old World Empires: Cultures of Power and Governance in Eurasia’. His previous works include ‘The Culture of Power and Governance in Pakistan 1947-2008’ and ‘Inquiry into the Culture of Power of the Subcontinent’. Niaz teaches history at the Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad. In an interview with TNS, he talks about his recent book as well as other issues related to the abysmal state of social sciences in our academia.

The News on Sunday: What challenges do you face as an academic historian working at a public sector university in Pakistan?

Ilhan Niaz: I am extremely fortunate that I work at the Quaid-i-Azam University and that the Department of History has an outstanding faculty and PhD alumni that have published about a dozen books over the past five years. Even though QAU is in the Global Top 500 ranking, we have to do without elementary support services, such as teaching or research assistants.

Getting funding for research within the university is difficult as the total research fund allocation is pitifully small (in the range of US$10-15,000 per year for the entire faculty of Social Sciences) and what little there is can only be availed after a struggle with bureaucratic red tape that would test the resolve of Winston Churchill. So, basically, if you are an academic historian in Pakistan you must accept that you are on your own and that you have to manage and perform in the absence of material inputs, research funding, or adequate support staff.

The fact that we have an inter-generational group of historians, many of whom have strong links to QAU, publishing meaningful work on a wide range of subjects is a tribute to their enterprise and endurance as well as to the academic vitality of the discipline.

TNS: How do you relate these challenges to the HEC and its policies towards the social sciences?

IN: I think the QAU Department of History is an excellent example of a programme that has performed exceptionally well without the HEC support, providing clear evidence that if you have people without resources they will still create output whereas if you have resources without people then you end up with a fancy campus and no real research. It would have been far wiser for the HEC to identify the top six or seven public sector universities and invest resources into transforming them into globally competitive centres of excellence.

If this had been done in time, today Pakistan might have 5-10 universities in the top 500 and these universities, through expansion of qualitatively superior programmes, could have brought quality higher education within the reach of citizens living outside major metropolitan centres.

For career academics at public sector universities working in the social sciences, HEC policies have in many ways been ruinous and demoralising. To cite just a few examples - a book published by an international publisher of high academic repute counts as only TWO research papers in the HEC’s reckoning, with a limit of two books maximum. Monographs, conference proceedings, chapters in edited books, count for naught even if they are the result of international peer review and/or research grants.

The much-vaunted Tenure Track System introduced by the HEC in 2005 and adopted by QAU in 2007 is now facing so many problems that many social scientists who opted for it have suffered irreparable damage to their careers and, seeing this damage, others are reluctant to join.

TNS: There is much emphasis on research funding for meeting national priorities, such as energy, economic crisis, food security, health, etc. Is there an applied component of historical research relevant to these problems?

IN: You have identified a number of key sectors and concerns and yes, the government does urge researchers to tackle actual problems being faced by Pakistan. Now, social sciences research strives at enhancing the available knowledge and wisdom on a given subject, and that understanding, if internalised by policy makers and civil servants, can help improve the quality of governance.

Again and again we are told that Pakistan’s problems are governance-related, and even clever technical solutions, if implemented by unwise, demoralised and self-aggrandising leaders and functionaries, serve no purpose.

TNS: Fair enough, but how is history relevant to the problems being faced by Pakistan today?

IN: Imagine a 30-year-old person who can only remember what happened over the past one year of his life. How functional would that person be? Now imagine a society that has existed for 5000 years, but most of its ruling elite knows very little about what happened more than 30 or 40 years ago. How functional would that society be? I would contend that in individual and collective instances that past is supremely relevant and without deep historical insight and rational self-knowledge a state cannot function.

TNS: Coming to your new book, Old World Empires, how would you sum up its central message?

IN: I would say that the central message of Old World Empires is that the historical experience of governance, shaped by human interaction with the natural environment, aided or impeded by demography, and propelled by universally applicable human nature, has shaped, and will continue to shape the fortunes of states. To ignore these factors or to deny objective validity to historical knowledge, both of which are eminently fashionable these days, imperils our ability to understand the past and shape the present so that the future may be better.

Old World Empires takes the framework developed in my earlier works and applies it to other parts of the world (China, Iran, Russia, Ottomans, Japan, Europe, the United Kingdom, and, of course, India).

TNS: How does this message engage with the popular discourse on history, governance, and politics?

IN: If by popular discourse you mean the hysterics of the electronic media, op-ed pieces by retired state functionaries who have nothing better left to do in life, and the five-star hotel conference circuit, then I suppose this message falls on deaf ears. Our fashionable and well-heeled experts are, as my mentor Zafar Iqbal Rathore said, "too busy being important" to do or understand very much. Powerful structures of donor patronage and chauvinism are in place and I don’t see them changing their materially rewarding way of doing things.

TNS: What were the major difficulties you faced in developing the framework contained in Old World Empires?

IN: The greatest challenges I faced were lack of funding for research and the absence of competent research assistants. These considerably slowed down progress, which is why it took a decade to research and write.

TNS: How do you see the future of history as a discipline in Pakistan?

IN: I think that Pakistan has a critical mass of productive historians and if someone were to decide to invest in this discipline, it could yield impressive results. In terms of history as a discipline in state schools and colleges, I am not optimistic given the combination of indoctrination and falling standards of teaching. In the eyes of the private sector universities, their primary function is to produce tolerably competent managerial and technical staff and they have little interest in anything beyond the bottom line.

History, which is a classical discipline and critical to developing a balanced and informed citizenry, is thus neglected by both the state and the market. In the case of the state this neglect is a manifestation of a lack of wisdom and incompetence, while in the case of the market the material incentives are not there. Projecting this into the future, history will continue to develop as an academic discipline at the university level, and we have the people who can perform at globally competitive standards. This trend at the university level, however, is not going to have a trickle down effect owing to the limitations of existing educational policy and lack of interest in the private sector.

TNS: Looking to the future, are you planning on another book? If so, what will it be about?

IN: Yes I am, and the next book will be about British India with reference to the development of institutions and habits of government. It will also reflect on India and Pakistan and has been picked up by IB Tauris. I hope to have it ready in time for India and Pakistan’s 70 years of independence.

TNS: Do you have a theme in mind for the next book? What problems will it address?

IN: Yes, I do have a theme in mind and that theme is tied to the problems the next book will seek to address. First, I think there is a need to take a more objective and dispassionate look at institutional development in British India both in terms of successes and failures. India’s democracy and Pakistan’s instability are both, in their own way, legacies of institutional development under the Raj. Second, the objective of the next book is to provide readers with a one-volume historical account of how institutions, such as the civil service, judiciary, jails, the military, and relationships between these institutions developed. Third, Pakistani historians have generally shied away from discussing the evolution of the British Indian state and much of what has been produced covers British India from the perspective of Muslim nationalism. Nearly 70 years after Independence, it is perhaps time to engage with British India as an entity in its own right.