A Scottish photographer, who was in Northwestern India roughly from 1882 to 1922, has a memorable album of monuments and personalities from that period

Fred Bremner is one of the hundreds of British commercial photographers who had established their studios in Indian cities and cantonments in the heydays of British Raj.

As an independent photographer, who worked largely in the far flung areas of the Raj, such as Balochistan and Sindh that are today parts of Pakistan, Bremner is more likely to be forgotten. His memoirs My Forty Years in India, (1883-1923) complete with twenty one autotype reproductions of his work, which Bremner privately issued twenty years after he retired to England, is perhaps the only record of a pioneer postcard publisher in Northwestern India.

The son of a professional photographer in Banff, Scotland, Bremner left school to join his father’s studio at an early age. With a hope for better prospects, he came to India as a struggling young man in 1882. He worked for his brother-in-law G. W. Lawrie, a small time photographer in Lucknow for six years. It helped him improve on his studio operations, which he had learnt during the six years of apprenticeship with his father in Scotland.

After the first two years of scouting neighbouring towns, for his next assignment he was sent 1500 miles away to work in Karachi where he arrived via Lahore in the summer of 1885. The British had captured Karachi in 1839 when it had a population of only ten thousand. However, at the time of his arrival, Karachi had become an important sea port for overseas commerce for Sindh, Balochistan and Punjab provinces and its population had risen to a hundred and fifty thousand.

Even though prior to his arrival he had little acquaintance there, but his contacts with a Scottish regiment in Karachi saved the day for him. He was soon able to meet a Barrack Master Richardson who belonged to the Scottish Lodge of Freemasons, the organisation Bremner had done business with earlier. Richardson took him as a paying guest and also introduced him to a chemist friend who allowed the young photographer to set up his studio tent in his yard.

Bremner worked in this set-up for the next five months. During this time he also hired two local assistants who helped him with retouching, printing, finishing and hand colouring. At the end of his assignment he left Karachi in 1886 and did not return to the city for the next two years. In April 1888 his contract with Lawrie had ended, his sister had died and he wanted to go home. So he returned to Karachi to take a ship for the British Isles.

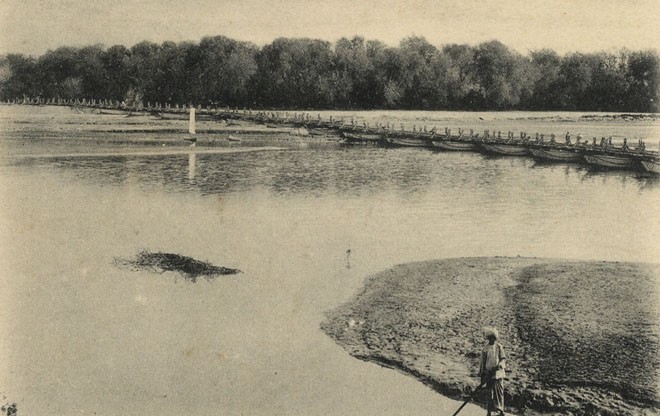

Upon his return from England in 1889, Bremner decided to open his studio in Karachi, the fledgling capital of Sindh. Through his savings he had bought some equipment from Glasgow and paid for the fair for himself and his one assistant whom he also had brought to Karachi with him. However, after paying for all that, he had very little money left to sustain. Luckily the opening of the Sukkur Bridge across the Indus by Lord Reay, Governor of the Bombay Province on March 25, 1889, afforded him photographic commissions to sustain his business.

More studios followed at various times in Quetta, Balochistan, and in Lahore and Rawalpindi in Punjab. The picture postcards carry the names of cities where Bremner had his studios at the time of issuing them. In 1910, Bremner opened a summer studio in Simla, the summer capital of the Raj. He married in the following year and was assisted in his work by his wife who newspaper ads referred to as "especially helpful with purdah-observing ladies".

Some of the prominent and distinguished sitters Bremner ‘shot’ during his years in India were the viceroys Lord Minto, Lord Hardinge, Lord Chelmsford, and Lord Reading; Lord Roberts of Kandahar, Lord Kitchener, and Sir Michael O’Dwyer, Governor of Punjab. He also photographed the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VIII) during his tour of India in 1922. Among the Indian nobility, he worked for the Nawab of Dholepore and later for the Maharajah of Jind, the Nawab of Maler Kotla, and the Maharajah of Kapurthala. He often photographed the Khan of Kalat in Balochistan.

Working with the British Indian army and occasionally for the member of British and Indian elite provided the mainstay of business, in addition to income from the retail shop. Since most newspapers even in the west carried a few pictures before 1910, situation in India was not any better. Colonial photographers like Bremner made the best possible use of growing European interest laden with imperial ambitions in picture postcards of foreign lands which were often colonised territory.

Picture postcards provided a lucrative outlet for their work, feeding back into their sales through commercial photography.

In 1900, he published a photographic album titled Baluchistan Illustrated, which contains the only surviving photographic records of Quetta before it was destroyed by the earthquake in 1931. The photographs and images of architectural monuments of Lahore also were a favourite subject for postcard publishers to reflect the ancient purity of traditional culture of the past. The hotspots of photographic activity for the picture postcard publishing were Mughal monuments such as Masjid Wazir Khan, and Lahore Fort. The Gates of Lahore, especially Delhi Gate and Lahori Gate were actively photographed and produced on postcards. The aesthetic conventions of these images -- the medium in which they were executed and the manner in which they were framed -- served to isolate the past from the present.

It was not uncommon for postcards to error in the title. Many titles and buildings were mismatched. Two glaring examples are of Mosque of Wazir Khan and Golden Mosque, which were heavily photographed and reproduced on the postcards. In one instance, the title of mosque of Wazir Khan is Pleasure Garden, Allahbad and Golden Mosque is titled Golden temple.

Such errors itself indicate the scattered nature of the production process and are tell-tale signs of their distant origin.