If a few skilful geniuses could solve the problems, no less than four dictators could have done it through their handpicked wizards in Pakistan

It’s not infrequent that we hear a chant or two about the formation of a government comprising technocrats. A democratically-elected government, the argument goes, is not suitable for a country such as Pakistan, for the populace is uneducated and can’t make intelligent decisions. The elected lot is even worse -- corrupt and uncouth.

As per this logic, the country needs a government of technical experts who are highly qualified and are hence honest and clean in reputation.

Such dispensation is expected to have the full support of the army and the judiciary since they themselves are pristine and come through a process of screening and selection that can produce nothing but gems of technical expertise so badly needed in this ‘wretched country’.

This mantra is often propagated by the so-called technocrats who have worked with dictators in the past and are still proud of that association. They defend their ‘marvellous’ contribution to the nation when the country was about to collapse due to the ’ of avaricious politicians.

Agreed, the display of extraordinary performance in a particular field deserves appreciation but the benefits of such feats need to be critically examined in a country with limited resources. If the technocratic expertise has devoured precious resources to produce some results, it may not have necessarily been due to any exceptional ability but only a byproduct of channelling disproportionate human and fiscal resources.

This critique should look into the opportunity cost the country has had to pay to achieve certain objectives mostly set by the technocrats themselves or by their top honcho.

The most common arguments to advocate technocracy are as follows: ‘knowledge and wisdom should reign supreme’; ‘reorganisation at the national level is direly needed’; ‘innovation is the name of the game’; ‘no nation can progress without an honest supreme leader who can oversee all administrative matters’.

Obviously, most of these protestations sound convincing and it is not easy to dispute them; nor can we raise fingers at the high level of competence the technocrats command in their own fields.

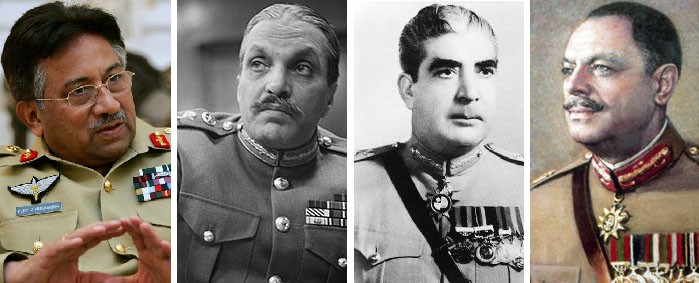

But, the issue is not that simple. If a few skilful geniuses could solve the problems, no less than four dictators could have done it through their handpicked wizards in Pakistan.

Here the question is not limited to technical adroitness in an operation such as deploying forces to take over the government buildings or conjuring up decades-old technology to detonate a bomb. What is at stake here is much broader social cohesion -- the craft of understanding how societies evolve not as a monolith but as a patchwork of competing forces. A compassionate insight is needed to grasp the nuances of social fabric before it starts fraying.

Most developed countries have not reached their present state by being quietly led by a few honest leaders; there have been profound developments in civil domains that have ushered these countries into their enviable avenues. Just by citing the examples of "a league of extraordinary gentlemen" one cannot simplify the matter. The challenge is to understand the role of individual in society. Probably a comparative analysis of collective efforts can help us reach a conclusion. Without any such evidence all claims for the supremacy of technocracy will remain hollow.

We might begin by differentiating between social development and economic growth. True that some dictators have led their countries to marvellous economic growth such as Chilean dictator General Augusto Pinochet did in 1970 and ’80s. It is not a secret anymore that he toppled Salvador Allende’s democratically-elected government in 1973 in connivance with the American CIA, and from 1973 to 1990 Chile demonstrated high economic growth rates. Similarly, in South Korea General Park Chung-hee ruled with an iron fist from 1961 to 1979 and put his country on the road to economic progress. In Pakistan, Generals Ayub Khan, Zia ul Haq, and Musharraf all had much better economic indicators, thanks to various factors including their services to the USA.

Socially speaking, these countries have paid a heavy price under dictatorships, not entirely understood by their own people. In Pakistan, at least two generations have already suffered immensely and another few generations will keep compensating for the periods of ‘economic growth’ and social decline.

The assumption that a government led by technical experts will bask in knowledge and wisdom is deeply flawed. Here probably we need to define knowledge and wisdom. These are epistemological questions that defy easy explanations; if knowledge can be accumulated by gathering a lot of information, can wisdom also be acquired in the same manner?

There is no simple answer to this.

Wisdom can hardly be marshalled by reading a lot in a specific field; probably some of it can be absorbed by trying to discern social factors. This requires an observant eye and a responsive demeanour. If you apply this criterion, our politicians such as Mian Iftikharuddin, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, Maulvi Tamizuddin Khan, Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, Ghaus Bhukhsh Bizinjo, Khan Abdul Wali Khan, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, Benazir Bhutto, Aitzaz Ahsan, Afrasayab Khattak, and Raza Rabbani -- just to name a few -- have displayed much more social acumen than all the dictators and technocrats combined. Though at times these politicians have compromised and acted in an unbefitting matter, a Suhrawardy or a Raza Rabbani would anytime be much wiser than a general such as Zia ul Haq, Hamid Gul, Musharraf, or a technocrat such as Shaukat Aziz or an AQ Khan.

The same applies to the hymn of ‘reorganisation’ or ‘reconstruction’. The technocrats never tire of reminding the nation that unless things are reorganised under their adept leadership, the rot will continue. Be it the Basic Democracy (BD) system under General Ayub Khan or a National Reconstruction Bureau (NRB) under Musharraf, the experts are always at hand. In most cases such apolitical ‘reorganisation’ worsens the rot.

Even if we accept the sincerity of such claims, how can we overlook the slaughter of democracy at the national level and be happy with a few organisational or local-level changes here and there?

Similarly an island of excellence at the higher education level should not blind us from the fact that while tall claims were being made at the higher level, education was starved at the primary and secondary level. Any reorganisation -- if it comes through a democratic process -- should be welcome, failing which a perestroika-type change might dismantle the Soviet Union itself.

The right to reorganise things lies with the democratically-elected leaders and not with a few technocrats.

The concept of democratic supremacy has evolved in centuries in the developed world and cannot be sacrificed at the altar of technocracy; be it the dismissal of General MacArthur in 1951 at the hands of the US President Harry Truman, or General McChrystal’s removal from command in Afghanistan and resignation in 2010, elected leaders -- and not selected ones -- should be allowed to make final decisions. That is why a defence minister need not be a military man and a minister for science need not be a scientist.

Interestingly, the attributes in favour of technocracy such as expertise, honesty, innovation, and know-how do not bother to touch upon people’s will. Probably it does not matter; what matters is the support from ‘selected’ elite such as the army and judiciary, with whom the technocrats are always on the same page.

Democracy makes leaders answerable to people and this accountability is not a good staple for technocrats since they are selected and don’t rely on popular support. We have seen big names in politics lose elections; but technocrats either leave the country -- as Shaukat Aziz did -- once their benefactor is gone, or keep trumpeting their achievements such as AQ Khan.

It appears that those who believe in the ‘selection of the best on merit’ as opposed to the election of the riff raff prefer to forget about the selected lot such as Justices Munir, Maulvi Mushtaq, Anwarul Haq, Irshad Hasan Khan and A H Dogar; or Generals such as Yahya Khan, AK Niazi, Tikka Khan, Ziaul Haq, and Hamid Gul -- all of them coming through a rigorous selection process apparently on merit, and leaving a trail of destruction in judicial, military, and political history of the country.

Another favourite cavil is that a democracy dominated by feudal lords will never promote education. While one can agree that feudal lords don’t want to promote education in society, we can’t deny that half of the time in our chequered history technocrats were sitting under an army dictator with the very same feudal lords who become despicable only in democracy. When Jawaharlal Nehru abolished feudalism by introducing land reforms, he had a strong democratic system behind him that bolstered his efforts.

In Pakistan, the dictators have buttressed feudalism; be it General Ayub Khan with Nawab of Kalabagh or General Musharraf with assorted samples of feudalism. The only condition appears to be loyalty; the most corrupt politicians are boon companions of the generals and technocrats alike, as long as they are loyal. The moment they want to make their own decisions as elected representatives of the people, they become uneducated, uncivilised, and corrupt.

The hypothesis that a feudal dominated assembly will never pass good legislations that go against its interests has no ground. If it were true the 18th Amendment would have never transferred most of the ministries to the provinces and the president of Pakistan would have never surrendered his powers to the PM, as Asif Ali Zardari did.

Feudalism is more associated with dictatorship than with democracy. Continuing democracy is the antidote to feudalism and an uninterrupted democratic process undiluted by technocratic seasonings is probably the answer.

Any technocratic promise to run the country more efficiently is as good a claim as the promise to run your car with water.