It continues to amaze me that a talk-show I hosted on television, forty-five years ago, is still remembered with fondness. I can only allude it to nostalgia which always colours memory and often glamorises it. The substantial success of the show was partly because of its novelty and partly because there was only one television channel in those days.

Success altered everything. Life began to feel over crowded. I relaxed, rather indiscriminately into a welter of publicity. I used to come out with smart comments on this and that, discussing such issues as whether or not women could make better politicians than men. My opinion was sought on books and paintings. My remarks were invariably misquoted or twisted thereby denuding them of whatever humour they might originally have had. My attire set a new trend.

I found people difficult to cope with. Their attitude towards me altered swiftly and completely. Ordinary acquaintances, to whom I had nodded or spoken casually, fastened on to me and assumed proprietary rights. Some of them had been insufferably snobbish towards me ten years ago. The question they asked, in an unctuous manner, was "how does it feel to be lionised?"

To reply to this sort of remark without complacency or overbearing modesty was not possible. I chose the later (it was less troublesome) and wore a permanent half-smile of self-deprecation for a long time. (I can still call it into use if necessary).

I did my stint of tape-cutting at fetes and picking the lucky numbers at fares and realised, with a sense of consternation, that the star treatment I received embarrassed me more that it gave me any satisfaction. I stopped accepting such invitations.

A little bit of soul-searching convinced me that the celebrity status bestowed upon me was a no more than froth. If I didn’t get a hold on myself I would be a lingering victim of my own success -- and worse -- I would begin to believe in the myth that I was as good, or even better, as I was being made out to be. I took the decision that I must give up my television engagement and go back to England to see if I could extend myself. If I hadn’t done that I would have been reduced to the status of a tv personality who recites verses effectively.

In England it was a new start for me. In show-business in the West, you are only as good as your last play and I had been away for quite a while. It took my agent, Terry Plunket-Greene, more than a year to establish my credentials once again. I was not able to rise to the firmament but I have no regrets about this because I was able to realise my own limitations.

More than anything else I learned to live with myself without fretting for company. I found that loneliness was nothing to be terrified of. A whole new world of introspection opened to me as a result. I became acutely aware that I knew very little about the language which I had acquired at a fairly early age. I could speak Urdu well enough, but did I really know the language?

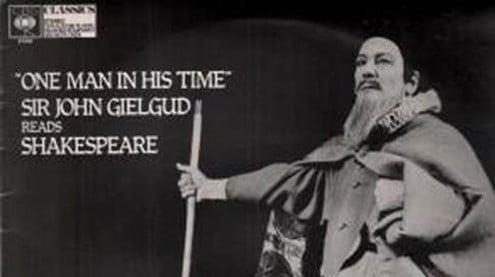

This irked me, especially after I saw Sir John Gielgud -- whom I call "the god of my idolatry" -- giving his recital, Ages of Man (a compilation of Shakespearean speeches) at the Queen’s Theatre. It transported me into the realm of beyond. It so mesmerised me that I could think of nothing but doing something similar in Urdu. All I needed, I told myself, was a stage, a script, a lectern with no props or any other embellishments. I did not for one moment think that I could match Sir John’s poise or oratory, or his voice, for that matter; I just became obsessed with the idea of having a go.

The question was: where do I begin? My small library in those days had only a few books in Urdu, collections of short stories or poems presented to me by their authors who lived in various parts of England. I needed to go through classical works and ferret appropriate stuff from them.

I took the liberty of ringing up Ralph Russell who headed the Urdu department at SOAS (School of Oriental and African Studies) and asked him if Urdu Studies had a good stock of Classics. I told him that I was planning to build a repertoire of classical and modern Urdu prose and poetry to be used in a recital. He was enthused with the idea and was most helpful. He not only assured me that their library was reasonably well stocked but suggested that the Urdu translation of Mir Taqi Mir’s Zikr-e-Mir by Bin Ali Bawahab should be considered as a part of the repertoire.

Also read: Looking back II

I delved into the SOAS library for quite some time. I read all the four volumes of Ratan Nath Sarshar Fasana-i-Azad, Rajab Ali Suroor’s Fasana-e-Ajaib, three volumes of Tilism-e-Hoshruba and was shattered to realise that I needed to work seriously on my Persian and Arabic.

Sarshar revealed to me an entirely new world of Urdu. The proverbs and idioms, many of which I had not come across till then, gripped me. His Rosmarrah (words used in everyday speech) was a mine of gold for me. His piquant sense of humour, his remarkable ear for the speech pattern of every character he introduces -- a nobleman or a wood-cutter, a princess or a chamber-maid, a priest or a crook -- is absolutely astounding.

Of all the nineteenth century Urdu classics, Fasana-i-Azad is a dizzying spinning wheel that enthrals you. Sarshar’s crisp, crystalline prose has yet to be equalled.

With the help of dictionaries, commentaries and annotations I was able to gain some insight into how a certain author tends to communicate his thought through florid, rhyming prose and how someone else expresses it introspectively, with long sentences.

But for me, at this stage, the most important thing was to have the text so under my belt as if it had been conceived by me. I am highly critical of my own work and it took me nearly a year to learn how to render different texts to my own satisfaction.

When you are offering a recital of ‘readings’ to an audience it is not just enough to read with a clear voice, good diction and a sense of what to inflect and what to throw away, you need to evoke the character of the prose as well. Let me illustrate:

(to be continued)