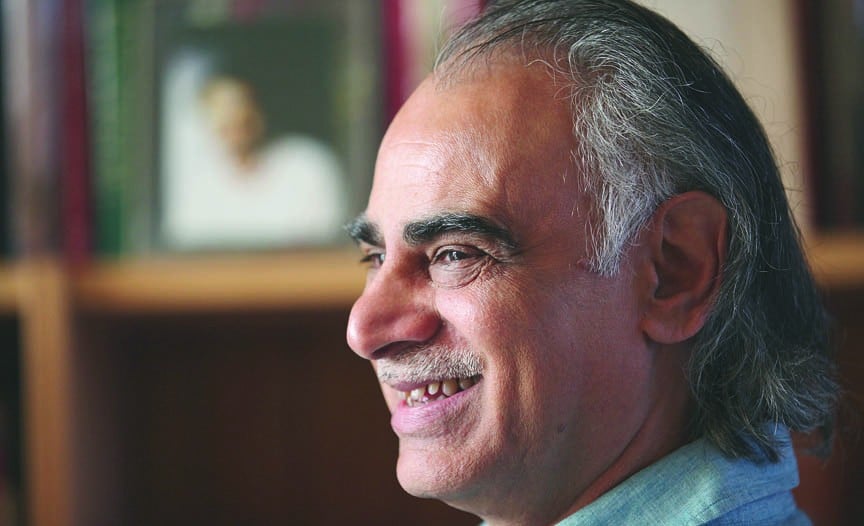

Ziauddin Sardar discussing some key issues facing Muslim societies and how must they be addressed

Ziauddin Sardar is a firm believer in engaging with Muslims and interpreting the Sharia according to the needs of contemporary times. That obviously is not the dominant thought in the current times where Islam is seen as a signifier of violence and when, in his own words, "one particular interpretation of Islam, which unfortunately is the most backward, narrow-minded and obscurantist, is threatening to become the dominant interpretation".

Whoever decided to put both Sardar and Pervez Hoodbhoy in one panel at the recently held Lahore Literary Festival was trying to be mischievous because the two have a not too pleasant history that goes back decades. The audience of the session thoroughly enjoyed their witty exchanges though, which were more a reflection of two diametrically-opposed schools of thought. One celebrated Cordoba as an example of history of tolerance while the other suggested no modern state could or should ever function like Cordoba; one argued in favour of ‘Islamic’ science while the other was all praise for ‘Western’ science.

Interestingly, both left too much in the listeners’ minds to think about.

Sardar was supposed to talk about his insightful new book Mecca: the Sacred City in his second session. The fidgety scholar was heard with rapt attention in a hall that was packed to capacity. Clearly, the city of Sardar’s childhood dreams resonates with most Muslims everywhere. His tone, however, remained irreverent evoking more laughter than a sacred subject would warrant.

That is how Lahore welcomed a son who left this country in 1960 for Britain, aged nine, and rose to become a writer of no less than fifty books and is now known as a public intellectual specialising in Muslim thought. In an interview with The News on Sunday, he discusses some of the key issues facing Muslim societies and how must they be addressed.

The News on Sunday: You are currently running this project called Critical Muslim which has its roots in what came to be known as the Arab Spring. What was the catalyst [for Arab Spring] and what then held it back?

Ziauddin Sardar: The truth is that nobody likes to live under a dictatorship. It’s a wrong assumption that the Arabs were happy with their dictators over the last forty years. They were agitating for democratic reforms in various ways.

The question is why did they succeed now and not before. This is because we are in a very specific epoch of human history, made unique because of a number of things. Now every generation says its era is unique. In the swinging 1960s, they claimed to have discovered environment and sex etc. But we have to look at it in a slightly longer term and see things that are peculiar to our times. One is the whole question of change. Earlier on, things changed over centuries, then decades, but now things are changing very rapidly and the rate of acceleration is very fast. The speed of change that we are seeing now is phenomenal and, in some cases, breathless.

Second, we have never been so connected as a human community in our history. Almost everyone in the world is connected to everyone else through various communication technologies like media, email, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and the 24-hour news channels.

Third, everything is globalised and the globe in a sense has shrunk. So this scale, speed of change and connectivity are unique phenomena of our times and together they make up a complex system. Most of our problems are complex, whether they are political, social or economic.

So when you have interconnectivity, complexity and things changing rapidly, you always get positive feedback which then changes things in a geometric fashion. Things multiply too fast and they almost always become chaotic. So you have to understand what I call the post-normal times. In this world, what we regarded as normal is increasingly becoming irrelevant: the economy doesn’t function in a normal way; social relations don’t function in a normal way; most of our assumptions that we took for granted in various disciplines, political science, biology or anthropology, do not hold anymore.

The Arab Spring is a post-normal phenomenon in that sense. It could not happen in the earlier period because the connectivity, the scale of things, the speed with which things change was not there. A small, insignificant incident -- of one particular trader objecting to being mistreated and setting himself on fire -- started a chain reaction. The 24-hour news showed him again and again, not just in Tunisia but in neighbouring countries too. Things multiplied with a profound impact and hence came the phenomenon of Arab spring.

But the interesting thing is that just as a post-normal situation can create a situation in favour of democratic forces very easily, it can also as easily create a situation in favour of dictatorial forces. So in Egypt, first we saw Mubarak being removed and Morsi coming to power, then a similar phenomenon threw out Morsi just as quickly as the fall of Mubarak. If you have rapid change, it takes time to stabilise the system, and if the system is unstable then other forces can manipulate the same system to try and change it in their favour.

TNS: To come back to the Critical Muslim project?

ZS: It is my thesis that most of the problems of the Muslim world boil down to lack of criticism, self-criticism, which also means lack of imagination and creativity. And if we are to change things for the better, first of all we have to critically engage with the world. Even before we do that, we have to appreciate that we live in a diverse and pluralistic world, with different notions of truth. That means we have to learn to appreciate other notions of truth and look at them with respect and dignity, and realise that our claim -- that we have the monopoly over sole truth -- looks quite absurd to others.

At the same time, we have to look critically at ourselves, our worldview. A great deal of what we believe in is manufactured dogma. A lot of this was manufactured in history but sometimes in front of our eyes and justified with all sorts of Ahadees which have no basis in authenticity or our history. So criticism is essential. Critical Muslim is essentially about looking at Islam, Muslims and the world critically. We critique everything -- the West, the Muslim societies, culture, science and technology. We believe that without thorough criticism, we cannot reach a true understanding of life and do something positive to change our societies.

TNS: In this context, how do you look at the ideal of freedom of expression as it is practised in the West which is to the annoyance of Muslims?

ZS: One of the first things you need to appreciate is that in a diverse world, different people will have different opinions and will express them differently. We need to learn to live with diversity. So if I am a believer, I will not dishonour the Prophet [pbuh] because he is a model of behaviour for me. But we have to realise we live in a world where four-fifth of the world is not a ‘believer’ and they may have their own opinion of the Prophet, just as we critique the Western values and they live with it.

But there is also a question of power here. In Critical Muslim critical engagement is also about analysing power. If you use your freedom of expression to abuse a community that has little or no power and is already marginalised, you’re committing injustice. I will stand up against you because I believe in justice and will stand up against injustice anywhere. The Charlie Hebdo affair is interesting in this context. Yes, I do support freedom of expression but I don’t support that an already alienated and minority community can be freely abused. That is not a very dignified way to express your freedom.

Freedom of expression works best when you are critiquing power and exploring the will to undermine power.

TNS: But then it all becomes very complex for Muslims because you don’t critique or do self-criticism…

ZS: The Muslims have to come to terms with the plurality, diversity and complexity of the world. If you feel hurt and take action, it will have consequences not just for you but for all the interconnections that your action may generate. An event that happens in the West and upsets the Muslims makes them go out and burn their own buses and shops, the same buses they will use the following day to go to work and the same shops they need to go out to and buy their groceries at. That is just senseless. We need to step back and find a more sophisticated way of protesting and undermining power.

TNS: The project has a kind of an academic feel. Have you thought of other modes of expression like film or drama maybe, considering that Muslims are not too much into reading?

ZS: It’s certainly a project that has academic and intellectual rigour but it is not solely for academics; it is meant for those who can read and think. We write fiction as well; every issue of Critical Muslim has short stories or poems. Our contention is that the Muslims have to see themselves as humans, and humans need music, arts, literature, science, technology, philosophy etc. You don’t become a human simply by having a religion. Religion may fulfill certain needs but it may not fulfill other needs. The goal of the project is that if we have that critical mass of people who are equipped to deal with themselves and their societies, they could then act as catalysts for change. Sometimes you need very few thinkers to change the society’s perceptions.

Yes, Muslims don’t read but in some places they do. In Pakistan, or Egypt, they don’t read a lot but Indonesia is a reading society and so is Turkey. We can’t make a generalisation about Muslims.

TNS: So, is this critical process taking place somewhere in the Muslim world?

ZS: Yes it is. In Turkey they have rethought many aspects of Islam. In Indonesia, the debate whether you can have an Islamic state was a long one and had a lot of depth, and they came to the conclusion that Islam and politics are linked, not through the state but through a civic society. What this means is that if you are a socially-conscious Muslim, you ought to bring your own moral and ethical outlook, express it openly in a civic context and debate and discuss it. This is quite an innovative way of being political, but not ideological in the sense that the whole idea of Islamic state has been constructed. So, they have kind of redefined what it means to be political -- it means to create a civic society.

In Morocco, they have totally redefined the personal aspect of the Sharia, not the criminal law but the personal law. You should go down and google mudawana.

Under the new Sharia, women have an equal right to divorce. In a divorce situation, children go to the mother, women have a right to alimony, a man cannot just divorce a woman, he has to actually go to a court and justify it, a man cannot take a second wife, women cannot be married off etc. All the conventional nonsense has been overturned, but by using the basic sources of Islam, i.e. Quran and Sunnah. If you dig out the whole constitution, you find the articles have footnotes saying where they are derived from. It is a Sharia which is just as valid as the classical Sharia but it is much more prepared for our own time.

Things are changing. In Morocco, instead of letting the conservative ulema interpret the Sharia for mudawana, the king decided to have female lawyers and other representatives of society who may not be alim but have a much greater understanding of contemporary times, laws etc. What happens is that there is no challenge to the conservative thought and authority, and this leads to uncritical thought.

TNS: You have been described both as a post-modernist as well as somebody who critiques post-modernism?

ZS: It is interesting how people like to put you in a box. They see things in black and white. I find that kind of absurd because it reflects that people can’t adjust to complexity. I am many things and nothing sometimes. Yes I am a post-modernist in the sense that post-modernism argued that the voiceless should have voice, and my entire life has been engaged in trying to fight on behalf of the voiceless. But I am not a post-modernist if post-modernism says that liberal secularism will give voice to the voiceless. I think the voiceless should have their own voice, their own worldview within which that voice is expressed. I am a post-modernist when they say there is more than one notion of truth but I am not one when they say that all meta-narratives, meaning the notions of truth, are meaningless. Well, clearly, Islam is not meaningless for me.

It’s a complex idea. There are bits of post-modernism that I agree with and bits that I strongly disagree with, and one of my books that has acquired a cultish status is called Postmodernism and the Other which looks at how post-modernism treats other cultures. In fact, the subtitle of the book, New imperialism of Western Culture, gives a conclusion of the book in a sense.

There are lots of theories coming from the West that we embrace uncritically. These theories turn out to be very sophisticated ways of perpetuating the status quo, of maintaining power within the Western structural framework. So, instead of blindly and uncritically accepting every new idea or theory that comes from the West, we need to critically engage with it, deconstruct it and show that often it has clay feet.

This whole idea of theory has become obsessive. People now want theory in all academic disciplines whether it’s culture studies or anthropology etc. Of course, you need theory but theory itself can become a dominant and oppressive structure, which doesnallow you to do anything. Some Pakistani academics shove theories of Said or Foucault, or Derrida unnecessarily in their work when they should be looking at their own cultures from within their own conceptual framework and come up with original ideas.

There is a kind of obsession which is quite uncritical and which I oppose.

TNS: Your work is associated with that of Ashis Nandy. Do you find that comparison justified?

ZS: Yes, Ashis and I in some sense think in the same way. We are both very strong critics of tradition, yet we believe in tradition. We believe you cannot have a solid identity without having a solid tradition behind you. Yet we know that tradition is problematic and can be suffocating and life-denying. I think both of us are essentially, at the end of the day, deconstructing power. We are obsessed about undermining power but not in a kind of one-dimensional way but within the framework of the complexity that we find ourselves in.

And, like me, he is a polymath. He is interested in film, science, technology, history, history of partition, globalisation. I don’t think he recognises this but he is an excellent polymath. One of the requirements of grappling with complexity and accelerating change is the ability to understand and, in some cases, master different disciplines. Engaging with the world through the lens of a single discipline does not work any more; you need interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary approaches. And you should have some capability of adjusting to the requirements of different perspectives.

TNS: There is a belief that Muslims are required to implement Allah’s law on earth and are, therefore, required to struggle for state power. Do you accept this conception of the Muslim’s individual as well as collective life?

ZS: Both of these beliefs are manufactured. First of all, how do we know the will of Allah; only Allah knows it. What we can do is to engage in a moral and ethical struggle starting with ourselves and then with our community and society. That takes us close to Islam. That’s all we can really do.

TNS: But then it’s about how you interpret it. Are the Jamaat-e-Islami, JUI, ISIS, Taliban and al-Qaeda not seeking state power in their own way? Their means might differ but not the ultimate objective?

ZS: Yes, they are seeking state power but this is a fundamental error. If you equate Islam with state, then religion becomes a reason of the state and that state becomes the power of religion. Basically you produce a totalitarian system. The very idea that Islam is equal to state is a totalitarian equation. We don’t have to go very far; we just have to see recent history. Wherever Islam has been equated with state, we have produced totalitarian systems, like Iran, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Afghanistan, you name it.

This also represents a very limited understanding of what power is. In the contemporary world, power comes in many different ways: in a way, the most powerful institution today is Google which is not a state; the most powerful force for change in contemporary times is Twitter, again not a state. If you look at how India has acquired power over the years, it has been through its culture. Bollywood is a very powerful institution which has had more influence on Pakistanis than the Taliban and all the religious groups put together in the last 60 years.

You need to realise there are different sources of power and some of the main sources are culture, knowledge and thought. Likewise, science and technology are major sources of power while here you have a society with hardly any notion of science.

TNS: But this is how we understand the various movements in the name of Islam that they seek an ideal state or caliphate. If it’s not that, then what is it that we seek as an ideal Islamic society? And what is the role of people, for example?

ZS: If we are seeking an ideal Islamic society, we are being utopians. And utopia has no people and no place. So, we are seeking an imaginary phantom that doesn’t really exist. Islam has to be lived with real people in the real world. It is about real daily struggle, to be ethical and good. We don’t even have a notion of what it is to be good in Islam in contemporary times. To say that offering your prayers five times a day and sporting a beard is good is ridiculous. We have a list of dos and don’ts which have no relevance to contemporary times. We have a law that was socially constructed in the 9th century with no relevance to the 21st century.

On top of that, we want to impose our notion of Islam on others. What Jamaat-e-Islami and others are seeking is not just state power; they are seeking to impose their own notion of Islam on everybody else.

TNS: How do you see all this in relation to how Western democracies have evolved and can a Muslim country go that way by having a parliament and election and still be Islamic?

ZS: Most of the problems of contemporary Muslim societies are due to the fact that we have not transcended our tribal nature. Look at Iraq, it is basically tribal. Syria is a good example of various tribes fighting each other, one in the name of Assad, one as Islamic State. But it is very much a tribal war. In Pakistan, too many tribal customs, including oppression of women, are justified in the name of Islam. It has also happened in history because Islamic law allowed certain tribal customs to become part of the Sharia, and we think it’s divine.

The question is how do we get these warring tribes to come together in a new arrangement that is based on some notion of accountable and participatory governance. And, that is a bigger challenge than the challenge of democracy.

TNS: But western democracy does partially address these questions.

ZS: Western democracy has some very good attributes but it has many things that don’t tally with us. For instance, if you need half a billion dollars to get a man into the White House, at least a hundred million dollars to be elected to the Senate or 50-60 million dollars to go the House of Representatives while the power really belongs to the lobbies and not to the elected representatives, it’s not much of a democracy. It depends on how you look at it. A democracy that only perpetuates the oligarchy, a certain kind of elite and accumulates wealth in a few hands as is happening in Europe and US is not true democracy.

What we need is open, participatory and accountable governance that we haven’t developed. The very idea of governance has become difficult and we think governing Pakistan is easy. No single party can govern Pakistan because it is a complex society. Governance itself is a complex phenomenon. We have problem of governance in Europe, Britain and the US. In the US, the government was shut down for several weeks. Where else in history have you seen this?

TNS: The idea of Muslim brotherhood is a glorified concept while the entire Muslim world is divided across sects and is fighting each other on sectarian grounds. People say that this is what religion does and that it is essentially sectarian. You have addressed it in an issue of the Critical Muslim but do you see the problem addressed in any other manner than it currently is?

ZS: This is what humans do and you go into any ideological framework and you will see this. Marxism had its Leninists, Trotskyites, Revolutionaries, anti-Revolutionaries, Counter Revolutionaries. In the end, one group kills everyone else and becomes the dominant group.

This idea of Islamic brotherhood is wonderful but it has never existed in history. In the formative phase, three of the four caliphs were murdered. You notice how many factions and divisions there were in the first 40-50 years after the death of the Holy Prophet -- Prophet’s youngest wife and his son-in-law fighting at the Battle of Camels, his grandson being massacred at Karbala. That doesn’t say much about the Ummah in the formative phase. So, it’s a great ideal to strive for but it has never actually existed in history.

Islam right from its inception had a problem with the ‘Other’, whether the Other means people of different interpretation or women or Christians or Jews or Sabians. That problem of Otherness has not been addressed. The Prophet addressed it in creating the community and the constitution in Medina. The Constitution of Medina is a phenomenally inclusive document. It mentions tribes by names, it names pagans, Sabians, Jews; it created a very pluralistic framework. But unfortunately after the Prophet’s death, that pluralism did not thrive as it should have. So, unless we come to terms with this problem with the Other, including different sects, we don’t really have much future as a thriving Muslim civilisation.

TNS: Violence or religious violence has shaped Pakistan especially at this stage. Have you tried to look at Pakistan as a unique case, where it is imperative for the citizens to assert their Islamic identity more than at any other place because it’s a country made in the name of Islam…

ZS: If you have to assert your Islamic identity it means you are unsure or insecure about your identity. If you have to wear it on your beard or T-shirt, there is something seriously wrong with you and you should see a psychiatrist. In that regard, I think most Pakistanis need to go for therapy.

But it is not just a Pakistani problem. It is the problem of Muslims everywhere unfortunately. And it’s a recent problem and not a historic one. It emerged after 1970 when we had one particular notion of Islam being propagated and imposed by various means on Muslim communities. And that is the Islam of Wahabism which does not tolerate other interpretations and has a very backward approach to religious thought. The Saudis opened up countless mosques for Muslims in the West, Islamabad, they financed madrassas, almost everywhere.

That’s a peculiar period of our history where one particular interpretation of Islam, which unfortunately is the most backward, narrow-minded and obscurantist, is threatening to become the dominant interpretation. If that happens, we are lost and Islam becomes a monolithic entity. No monolithic entity can survive in this diverse, plural, complex world.

TNS: Your book Mecca is being widely discussed. Do you think it will put a stop to any further physical transformation of the city?

ZS: No, the city has already been transformed beyond recognition. There is no history and culture left in Mecca. What has happened can not be undone. The book is only a lament over that lost history.