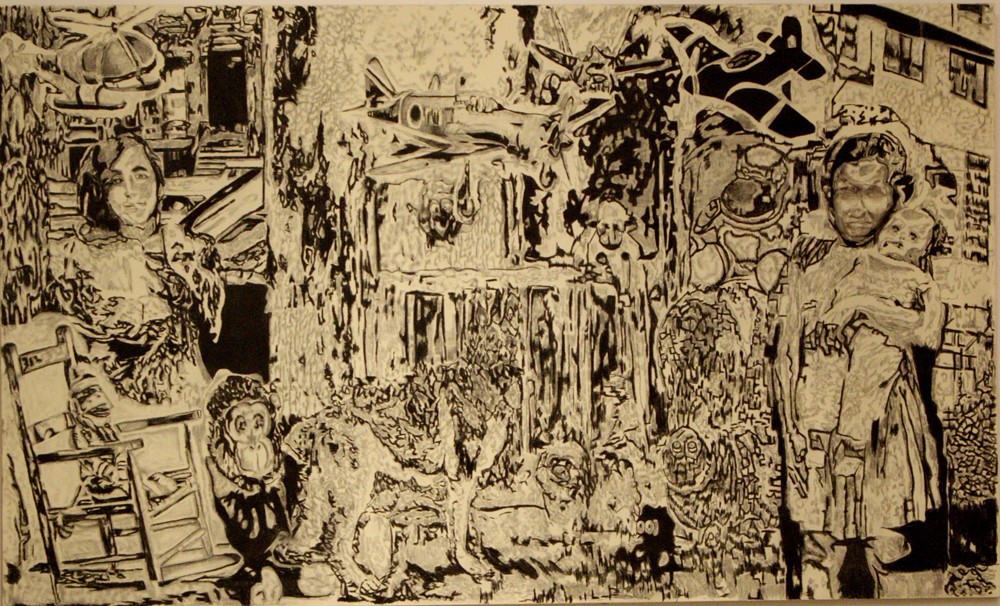

The thesis show of the Fine Arts Department of NCA is a reflection of the penchant to examine material not just as a means but as a conceptual facet of the work

Tappa is sung both as a folk and a classical form in our music. Traditionally many forms of poetry are sung like kaafi, ghazal, qissas/dastaan, and to the layman there appears to be no difference between the poetical and the musical forms. These forms or terms are used by them interchangeably without batting an eyelid.

Tappa or boli is generally seen as a form of poetry which is also sung. Unlike the kaafi which is considered a very prestigious form of poetry, both in Punjabi and Sindhi, tappa is more lok, if distinctions need to be made between the various forms of folk poetry and thus is even closer to the everyday expression of the people living in the Punjab.

At the same time, the virtue of such poetry is that it is much closer to the colloquial expression and retains the vitality of a language which has the vibrancy of the slang and therefore is ever susceptible to new imagery, structures and phrases which a more formal expression of the language may be hesitant to incorporate. But the freedom and the openness to change is what distinguishes this form or that of the bolis from other forms in the language. The vitality and the freshness of expression is thus its valuable virtue or asset. In its music rendition, the same simplicity and uncomplicated nature of the composition is upheld as its prime quality.

But some two centuries ago tappa gradually got incorporated into the high classical tradition and over a period of time was raised to the level of the kheyal and tarana by some of the leading gaiks of the time. While in some parts of the subcontinent, it was known for its rustic and simple renditions, in others particularly in Lucknow it was considered the most difficult form of gaiki, even more than the kheyal as the latter developed during the course of the nineteenth century.

The credit for elevating the form goes to Ghulam Nabi Shori who was fully responsible for establishing it as a proper form to be sung at the most important and prestigious forums of music in the subcontinent. Who was this Ghulam Nabi Shori who created a new form of classical gaiki? According to the author Ustad Badruzzaman he was the son of Ghulam Rasool who had migrated from Kasur in the Punjab to Delhi and was in the service of the Mughal monarch Muhammed Shah Rangeela. But with the death of the monarch and the gradual disintegration of the mighty Mughal central court at Delhi, like so many other artists, the poets and men of letters migrated in search of patronage to the court of Awadh nawabs.

There while he also performed and established himself, he also initiated his son Ghulam Nabi Shori to perform who soon made a place in his own right in the court, creating the new form and laying the foundation of the various gharanas that went on to safeguard the kheyal gaiki in the nineteenth and twentieth century.

So, according to the author, it was actually Kasur that played a pivotal role in all this as Tajdin a qawwal from Kasur had gone to Delhi because of his immense talent at the darbar of Muhammed Shah Rangeela where at that time Nemat Khan Sadarang was also present. Nemat Khan is credited with the creation of kheyal and his bandishes with his pseudonym Sadarang are still sung by the gaiks of kheyal. Tajdin’s son was Ghulam Rasool.

All the kheyal gharanas traced their origins back to Makhan Khan and Shakkar Khan who resided in Lucknow. They were either brothers or were related or probably shared a parent each. Some other authors are not so sure of their exact relationship but Badruzzaman is certain of their relationship with Ghulam Rasool being that of maternal grandsons. Makhan Khan and Shakkar Khan did not get along and probably the enmity was due to their professional rivalry. Such jealousies leading to enmities and then conspiracies to maim, kill and/or incapacitate are the stuff of music lore. Apparently these two brothers and then their progeny were responsible for founding most of the gharanas through their progeny like Bare Muhammed Khan.

Kasur has been one of the centres of music in the subcontinent. It is said that Mian Tansen was granted a jagir in Kasur by Emperor Akbar. He visited his jagir at least once and was feted by the musicians of Kasur. It is said that he was so impressed by these musicians that he bequeathed his jagir to them. Kasur by virtue of its prowess in music was also known as Choti Gwalior.

The book has many rare bandishes in Punjabi of the various tappas that have been composed and sung by many outstanding vocalists. It is said that it was the influence of Tajdin and his progeny that many of the bandishes in Punjabi were composed in the Delhi/Lucknow areas by some of the outstanding gaiks including Nemat Khan Sadarang.

Kasur also has the distinction of being the resting place of Bulleh Shah. It is said that two qawwals, Sona Khan and Mian Chandi, were known as Bulleh Shahi qawwals. There was a tradition of qawwali in Kasur and Chotte Ghulam Ali Khan often sang the qawwali as demonstration in private mehfils which was very different from the qawwali form that one hears these days. It was also without the monotonous rhythmic pattern reinforced by the clapping of hands.

The book is a valuable addition because the written material on music is scant and some that is available is mostly about hearsay. Badruzzaman besides his grasp of the practical aspects of music is also quite thorough in his scholarship as he followed the basic principles of research. Like his other works this, too, is properly referenced.