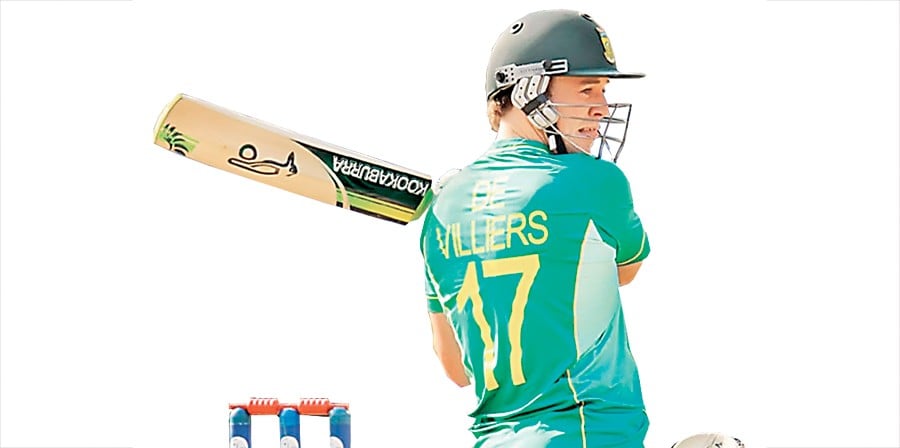

AB de Villiers may come across as something of a fictional superhero on the field. But his relatively underplayed fallibility off it shows that he is human too

AB de Villiers makes people want to do what they should not want to do. Countless bowlers will attest to that, as countless more will, before he hangs up his audacity.

West Indies know this only too well. The innings de Villiers unleashed on them at the Wanderers in January proved that even the most innovative batsman in the game is not done innovating.

That de Villiers scored the fastest ODI hundred that day was peripheral, the halo on the angel. How he scored it mattered more. There was no way to bowl to him and escape a hiding; no chance of holing up somewhere until the hurricane blew itself out. West Indies needed all hands on deck, and that was not nearly enough to stop de Villiers until the 49th over.

De Villiers has not become a better or more assertive player suddenly. It is simply that a light that has for years been hidden under the bushels of players like Jacques Kallis and Graeme Smith has emerged into all its incandescent glory. He has always been this good. Others have just been more trusted in a culture that remains uneasy with the stupendous, and with de Villiers, stupendous comes standard.

"You have to read the game to see what the bowler is trying to do," he said of that innings, but it may as well have been a career mantra. "You can’t just let him bowl at you; you have to try and take the initiative and put him under pressure… you’ve got to take the initiative and take it to the bowler."

Unlike Hashim Amla, who seems to barely move a muscle -- and never changes his gloves -- to pile up his mountains of runs, or Faf du Plessis, who will bat all day and more and to hell with how many runs he does not score, or Quinton de Kock, whose batting is orthodoxy on steroids, de Villiers is a mad inventor. Unlike Dr Frankenstein’s, however, his creations are seamless and scar-free.

From the time the ball leaves the bowler’s hand to the moment it needs to be dealt with, de Villiers is capable of mentally flipping through even the most modern coaching manual, choosing two or three options, deciding against any or all of them, and fashioning something bespoke instead; something that looks like it has been part of cricket for much longer than the nanosecond he has taken to devise it.

More often than not, de Villiers’ choice proves perfect -- as if he has for years been cartwheeling down the pitch at diabolical diagonals to connect with the ball and propel it way out of reach of any fielder.

De Villiers bats like a tightrope walker not bothered to check whether his rope is tight. If it is not, he will die a messy death. If it is, life goes on. Somehow, de Villiers is still flying high in rude health.

He does it all without arrogance, without showing off. A small example, extreme in its own way: after lunch on day three of the third Test against West Indies at Newlands in January, de Villiers whipped Sulieman Benn behind square leg and deep into the outfield.

On his way back to the crease to complete a second run, he stopped some three metres short of his ground. A spot of disturbed pitch had caught his eye. So he paused to prod it down. The throw was already arcing from the outfield towards the wicketkeeper when de Villiers interrupted his return. He knew this, and still he stood there as if tending his front lawn on a lazy Sunday. But he also knew, by some vectorial instinct, exactly how long he needed to make it back without causing undue alarm. He did.

Few in the crowd reacted to this blatant violation of the received wisdom of "Cricket: How To Play". Perhaps they did not see it. Perhaps they had seen it -- or something like it -- too many times before to pay it much heed. We are dealing with AB de Villiers, after all and this is too easy.

It is away from the crease that de Villiers is most interesting. When he has a bat in his hands, he knows how to get from A to B in record time. Off the field, he walks a crooked line to get there.

De Villiers is canny enough not to be drawn into discussions about South Africa’s attempts to undo the damage of apartheid. Officially, quota selections do not exist, which only gives rise to unfair whispers when black players are picked. White players never seem to have their credentials questioned the same way.

His silence on the issue would be pertinent if it was not also the default position of his team-mates. The players are neither scared nor calculating by not speaking out: they simply do not care. As the No. 1 Test team in the world, why would they? But their silence prevents them from reaching that far more important goal: a more representative team on the field.

There is a more intriguing side, however, as evident in the dithering over de Villiers’ wicketkeeping duties. He has vacillated with something close to impunity between saying he will do anything his team needs and, by voicing his reluctance to keep wicket because of a chronic back problem, not exactly doing anything his team needs.

He was not behind the stumps in either of South Africa’s Tests in Sri Lanka last July, and his statements then were strangely ambiguous. "In the last game I had that ‘hammy’ issue. That’s sort of recovered, but my back has always been an issue.

"It’s difficult to take on the gloves, especially keeping in mind that I haven’t kept for -- what is it -- six or seven months now. So with that injury and a two-day turnaround after the day off yesterday, for me to get into shape with my gloves on, and considering my back, would be a little bit unfair.

When de Kock tore ankle ligaments warming up for the third day of the first Test against West Indies in Centurion in December, de Villiers was the logical emergency replacement. But going by what he said in June, he would surely not do the job in the following Test. Yes, he would. And in the third Test too.

So which is it? Does de Villiers want to keep wicket or not? Or does he want to do what the team prefers? Or to tell us -- and the public -- what he thinks we want to hear?

Part of this problem is that modern cricketers are conditioned to be positive in the press, no matter what. De Villiers, nowhere near as sensible as someone like Amla, tends to say what he thinks is the safest thing, as per the suits’ wont. But sometimes he forgets who and what he is, and silliness like "We were the better team in Australia" tumbles forth (so how come the Aussies won that November one-day series 4-1?); or, "jet-lag comes into play [flying from Perth to Canberra]", which is, um, a three-hour time difference.

In moments like these it is difficult for those who regularly see and hear de Villiers to curb the cruel thought that he could just be brainlessly brilliant.

On the field, he is a certified genius. Off it, he has the manners of an impeccably raised young man and that of the ambassador to Lichtenstein trying to negotiate peace in the Middle East: not a little out of his depth.

This is not meant as spiteful. In fact, de Villiers will not take umbrage, mostly because he will not have read it. He knows better than to take notice of what is written about him in the media.

As a schoolboy prodigy, de Villiers did amazing things in many sports; on a cricket ground, a rugby field, a tennis court, a swimming pool or a golf course. Why cricket? Rugby careers are shorter and ask a higher physical price, and none of those other sports can be turned into a career in South Africa.

De Villiers was famous in his milieu long before he became the giant we know today. And Pretoria is not any old milieu -- it is a place where school sport is taken only slightly less seriously than what happens at senior level.

So de Villiers’ name, face and exploits have been splashed across newspapers since he was a boy. That he attended the prestigious Afrikaanse Hoer Seunskool did not hurt his assimilation into the ranks of the rarefied.

But after the 2011 World Cup, de Villiers went where even he had not gone before. Not at any level had he captained a cricket team. Often du Plessis -- who went to the same school and played for many of the same teams -- took that responsibility. De Villiers was simply the star, not the leader. When Graeme Smith relinquished those reins, however, de Villiers picked them up.

Why? Call it growing up, or answering the call that would have been buzzing inside him because of his conservative, Calvinist upbringing; or even becoming a little bored with the diminishing challenge of flaying attacks.

Initially he struggled to get his head around managing an attack in the accepted manner. But Gary Kirsten’s philosophy of spreading the leadership load among the senior players allowed de Villiers the time and space he needed to grow into captaincy. He was always going to set inspirational examples, but the smaller stuff like over rates and field placing tended to trip him up -- not unlike the engineers on the Brooklyn Bridge forgetting to check that all the nuts and bolts had been tightened.

De Villiers bats like a tightrope walker not bothered to check whether his rope is tight. If it is not, he will die a messy death. If it is, life goes on

Now the World Cup looms for him like that spire atop the Chrysler Building, a shimmering prize on a towering perch that will take some climbing. No South African captain has been up there, or even ventured as high as the final. Will de Villiers be different? He is already, in that for all his ability to play cricket to a level rarely seen, he can be clumsy in the public glare. And he has had to learn how to captain a team. But despite his missteps he has shown himself to be a keen student of the lessons of leadership.

De Villiers is what results when an ordinary man is given extraordinary gifts. He goes to the World Cup with a team that has, by its standards, an ordinary record in major tournaments. But Amla and Steyn and de Villiers himself lend this generation the gleam of the extraordinary. All were present that extraordinary night in Dhaka four years ago when an ordinary New Zealand team found a way to beat South Africa’s extraordinaires in their World Cup quarter-final.

That was then. Now the trio are at or near the pinnacle of the game. They know that, just as they know they will never be better players. This may not turn out to be their World Cup, but they will never have a chance as good.

So if South Africa do the unthinkable and win it, de Villiers would not be able to claim as much credit as, say, Imran Khan was entitled to when Pakistan triumphed in 1992. He would not want it.

At the crease, de Villiers knows no boundaries. But they are strewn elsewhere in his life -- when he is captaining his team, or trying to tiptoe around a tricky issue in a press conference, or sitting in a restaurant with his wife. The difference between him and others of similar stature is that de Villiers knows where the invisible line is drawn; where the star ends and the person begins.

As long as he does not allow that line to blur, as long as he remembers that he has weaknesses to go with his many strengths, as long as he is who he is, he will not lunch alone. --Cricinfo