Without giving FATA a clear constitutional and political status, it would be impossible to prevent the return of militants and terrorists in the region

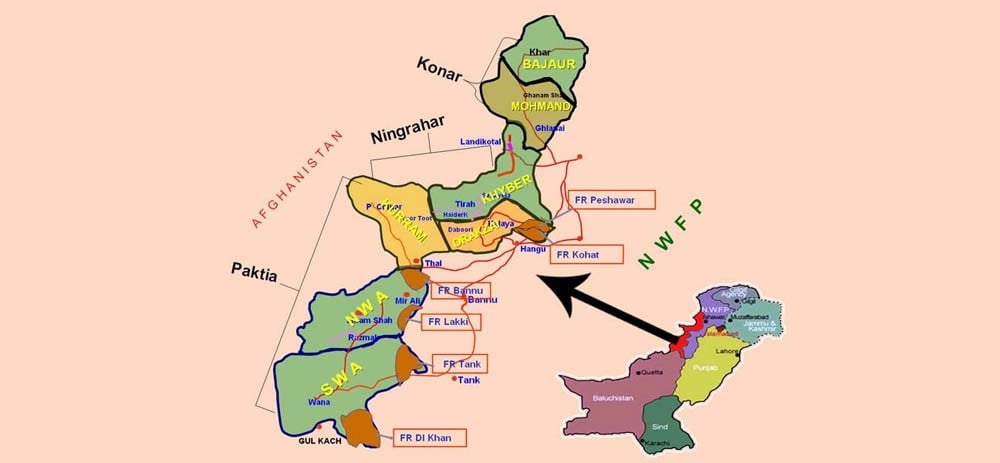

The tribal areas of Pakistan have been instrumental in militancy and terrorism by groups like the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), al Qaeda and many other local, national and international outfits. Without securing FATA, terrorism in the country cannot be ended. The million dollar question is how to secure FATA. For getting answer to this very complex question, we have to first track down how various Pakistani and international groups emerged or got sanctuaries in the tribal region and what factors facilitated their rise and entrenchment there.

The foremost reasons for the rise of militancy in the region have been political, administrative and governance failures in these areas straddling Pakistan’s border with Afghanistan. This vacuum was the upshot of indeterminate political-legal status of FATA. Though the Constitution of Pakistan recognises FATA as an integral part of the country, at the same time the law of the land is not enforceable there. There has been little attention from successive governments to address this anomaly.

FATA was never in focus of Islamabad until the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan in December 1979. Even then it was not to develop or mainstream the region but to use it as a springboard and rallying ground for anti-Soviet fighters and global organisations.

The withdrawal of Soviet forces from Afghanistan in the face of stiff resistance from the Pakistan-backed Afghan Mujahideen could not compel our decision-makers to focus somewhat on FATA. Instead, our strategists turned a blind eye towards the tribal areas rendering the region as a free field for militants.

Those who got shelter in FATA included extremists and militants from the Pakhtun-dominated Khyber Pakhtunkhwa; from the Punjab, who coalesced to transform into Punjabi Taliban; Haqqani Network and Afghan Taliban from Afghanistan; Uzbek and Chechen fighters from Central Asia; Uighur Turks from China, Arab al Qaeda fighters from Gulf and the Middle East and individual extremists and militants from across the world.

Had Pakistani authorities focused on developing and governing the tribal areas, the scale of the militants’ percolation in the tribal areas in the wake of the 9/11 could have been manageable. Unfortunately, this was not done and this was merely due to the absence of farsightedness on part of our strategists and policy formulators.

In June this year, however, Pakistan decided to launch an offensive in the NWA. This operation has been very successful and by now most of the district has been secured and extremists and terrorists are on the run. The December 16 Peshawar school tragedy has increased the importance of securing FATA manifold and this has been emphasised in the 20-point National Action Plan (NAP) drafted by the entire spectrum of the country’s political leadership.

Therefore, securing the entire FATA including the NWA has become critically important at this juncture. But clearing FATA is only half of the task. The other half which is rather more important is how to fully secure FATA in the post-operations period so as to prevent the region to be used by terrorists as a launching pad for attacks in Pakistan.

The region is still governed by the colonial legal framework, the Frontier Crimes Regulation (FCR). The stress on the word ‘crime’ in the legal framework speaks for itself that the region is considered as a lawless and uncivilised territory. This may be correct to a certain extent but the new educated and civilised generation of FATA is demanding more civilised and modern self-governing institutions. The presence of the FCR and its inability to cater to the socio-political and above all human needs of the dwellers of FATA and the political and legal vacuum thereof resulted in the rise of extremism and terrorism.

So without giving FATA a clear constitutional and political status, it would be impossible to prevent the return of militants and terrorists in the region. Giving provincial status to FATA would help provide the much-needed enabling environs for the civilized and modern governing and political structures. For instance, after giving a provincial status to FATA a provincial assembly or legislative body could be formed. By formation of such an institution the tribal character and rules could be institutionalised and transformed into civilised structures of power and authority.

However, only establishing a provincial assembly would not suffice to address the complex administrative problems and development needs of FATA and their inhabitants. Therefore, the other most important step would be to establish elected municipal or local councils. This is the only mechanism through which the state writ in the tribal areas could be established.

It may be recalled that the British colonialists had always been insisting on training the people of India the art of self-governance so that they could run sustainable structures of power and authority. Unfortunately, the British rulers of India could not train the people of FATA the art of self-governance as the region and its people needed it the most. But it seems that the British international policy dictated its strategy in FATA as it wanted the region to serve as a buffer between mainland India and Afghanistan and beyond Czarist Russia and later Soviet Union, after the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution.

Unfortunately, successive Pakistani governments adopted the same policy and attitude towards the tribal areas. This attitude needs to be changed and the historical wrongs which our strategists and policy formulators committed with reference to the tribal areas needs to be rectified. If we fail this time, we cannot prevent a disaster of gargantuan proportions in the region.