The IS has attracted relatively more support in Pakistan in absence of a strong militant group like the Afghan Taliban and also due to the growing divisions in the TTP

The move by the Islamic State (IS) to finally set up its chapters in Afghanistan and Pakistan has received relatively better response in the latter where more militants have joined it compared to the former.

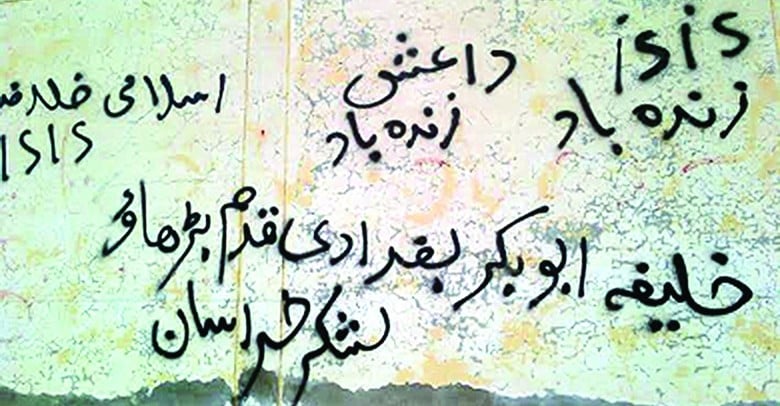

The unit is named Khurasan after the ancient name of the vast region comprising parts of Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan and a few Central Asian states. A growing number of militants in the recent past have been adding ‘Khurasani’ to their names to highlight their belief in a saying of the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) that the final battle leading to decisive victory of Muslims against members of other faiths would begin in Khurasan and end up in the Middle East. The name Khurasan also helped revive memories of a glorious past when there was powerful Islamic rule in the region.

The IS made the decision to extend its activities to Khurasan after about 100 Taliban fighters from Afghanistan and Pakistan released a video in which they pledged allegiance to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, who has been declared caliph by the militant group now controlling large swathes of territory in Iraq and Syria. The video was convincing enough to prompt the IS leadership that it was time to establish the chapter in Khurasan.

In the video, the Taliban fighters are riding horses carrying the distinctive black flags of the IS. The video also mentioned the commanders for three provinces in Afghanistan and several others in Pakistan. The oath of allegiance in the footage is spoken in Arabic to make it easier for the Arabic-speaking IS high command to understand the language.

Many from the same group of Afghan and Pakistani Taliban fighters had pledged allegiance to the IS about two months ago, but the latter had kept quiet instead of welcoming them to its fold. In fact, this had frustrated the Afghan and Pakistani militants as they were hoping to be warmly welcomed into the IS fold. The IS leadership apparently wanted to find out more about the Taliban commanders before accepting their allegiance and appointing them as its representatives in Afghanistan and Pakistan. It explained the care being exercised by the IS before allowing militants from faraway places to join its ranks.

Hafiz Saeed Khan Orakzai, the former Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) head for Orakzai Agency in Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas (Fata), has been appointed by the IS as its ameer for Khurasan. He was one of the strong contenders for the position of the TTP head when Hakimullah Mehsud was killed in a US drone strike in North Waziristan on November 1, 2013. The job eventually went to the Swat Taliban chief Maulana Fazlullah as a compromise candidate due to the apparent unwillingness of the other contenders to accept each other as the TTP head.

As predicted, the Afghanistan-based Fazlullah proved a weak leader unable to keep the TTP intact. The TTP is now split and, among others, Hafiz Saeed Orakzai, also revolted against Fazlullah’s leadership, set up his own group along with five other Pakistani Taliban commanders and eventually declared allegiance to the IS. In fact, the differences in the TTP ranks and weakening of the group’s bonds with al-Qaeda and the Afghan Taliban is one of the major reasons for the rise of the IS in the Af-Pak region and its growing strength at al-Qaeda’s expense.

Mulla Abdur Rauf Khadim, named as the deputy leader of the IS Khurasan chapter, is a former Guantanamo prisoner who came into prominence after his release from the infamous US prison. Despite being in his early 30s, he quickly rose in the ranks of the Afghan Taliban movement because spending time in Guantanamo has become a badge of honour for militants worldwide. Surprisingly, Khadim has yet to publicly announce his joining the IS, though reports had earlier emerged that he was leading a group of former Afghan Taliban militants in Helmand province and overseeing the raising the group’s black flags in Baghran and other districts. Subsequently, unsubstantiated reports claimed that the Afghan Taliban had captured Khadim and 45 of his men in Helmand. If true, this won’t be surprising as the Mulla Omar-led Taliban movement doesn’t allow any dissidents in its ranks and is known to kill or capture anyone showing disloyalty.

In case of Khadim, the anger of the mainstream Afghan Taliban movement would be even more pronounced as Khadim had developed differences with the top leadership after having been bestowed with the important job of one of its deputy leaders. At the time, poor health was cited as the cause of Khadim’s decision to step down from his position, though he continued to stay loyal to Mulla Omar and reportedly shifted to the Taliban stronghold of Helmand.

The Afghan Taliban movement, which calls itself the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan -- the name given to the country when Taliban were in power from 1996-2001, has largely stayed intact under the leadership of its Amirul Momineen (Commander of the Faithful) Mulla Omar. Defections have been few and those betraying the movement have been eliminated or have been rendered insignificant. It would, therefore, be difficult for the IS to gain foothold in Afghanistan. The three ameers named for Logar, Kunar and Nangarhar provinces aren’t well-known and it is doubtful if they have enough armed men under their command.

In comparison, the IS has attracted relatively more support in Pakistan in absence of a strong militant group like the Afghan Taliban and also due to the growing divisions in the TTP. However, in Pakistan also the IS-affiliated militants failed to find many supporters and known commanders in Swat and rest of Malakand division and in North and South Waziristan. It has drawn most of its support in Orakzai Agency, the tribal home of the Khurasan chapter head Hafiz Saeed Orakzai and the former TTP spokesman Shahidullah Shahid, whose original name is Sheikh Maqbool. It was also able to trigger defections from the TTP in Kurram and Khyber tribal regions and in the Peshawar district where commander Mufti Hassan has joined the IS. Some militants in their individual capacity in different parts of Pakistan have also quietly joined the IS and some of them have already been apprehended if one were to believe the law-enforcement and security agencies.

To be candid, the IS at this point in time doesn’t have any real prospects of making headway in Afghanistan. In Pakistan too it would have to struggle to strengthen its shrinking base after the militants’ retreat from some of their strongholds in the tribal areas and Malakand division and the split in the TTP. Those who have aligned with the IS were already fighting the Pakistani state and their strength and weaknesses are known.

It seems no new recruits are joining the IS in Pakistan and nobody knows if any militants from the Arab countries from where the group has drawn most of its strength have been able to reach the Af-Pak region to organise the IS Khurasan. The veteran Arab, Central Asian and other foreign fighters hiding in the border regions of Afghanistan and Pakistan still prefer to remain aligned to al-Qaeda due to the strength of their past association.

The IS in Khurasan has yet to launch its military operations in Afghanistan and Pakistan. It would certainly claim responsibility for any attack undertaken by its members or allied militant factions. It is possible the leaders of the IS in Khurasan are still trying to figure out their next plan of action based on directives received from Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and his spokesman Abu Muhammad al-Adnani.

Communicating with the IS leadership in Iraq and Syria would be a challenge as all of them are wanted and a top target for the US and scores of Western and regional powers through their well-resourced spy agencies. The IS in Khurasan would definitely want to carry out attacks in Afghanistan, particularly against the remaining US-led Nato forces, but its capacity to do so is limited. It could undertake such attacks in Pakistan, but a decision would first have to be taken in consultation with the IS caliph Baghdadi to go for Western targets in the country or take on the Pakistani state and its security forces.

Unlike the past when the TTP commanders were largely independent in their actions and fairly autonomous in their working, the IS Khurasan would have to operate under the discipline of the IS high command based in faraway Middle East. This could restrict the IS in Khurasan in its decision-making and operations.