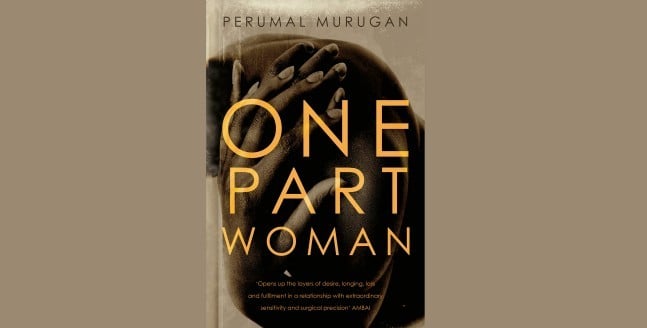

Tamil writer Perumal Murugan’s novel One Part Woman raises some new thoughts about freedom of expression

Is writing a political act? How is a creative piece to be perceived: as pure art, as propaganda or anything in between? What are acceptable versus unacceptable responses to a work of art? Finally, are writers and artistes counting on notoriety of outrage to propel themselves out of obscurity?

I read voraciously. Yet until the issue erupted just two weeks ago, I hadn’t heard of Tamil writer Perumal Murugan. That’s okay, he’s probably not heard of me. For the writing scene as the rest of enterprise in India is burgeoning so briskly that to attempt to make sense of it all is doomed to be exhausting and incomplete.

One Part Woman (Mathorupagan) is set in a lesser locale in the contours of the Tamil literary landscape, Thiruchengodu in Kongunadu. The story is from the early last century, of a childless couple Kali and Ponna who in their desperation for offspring try every recourse until Ponna is advised to take advantage of a religious festival where for one night only childless women are permitted time with another man in order to conceive. For the Lord descends into all devotees for that one sacred night and all children conceived thus are God’s children. Infidelity or one night stands are not new social phenomena. Neither are Indians so morally sensitive that a mention of its possibility in any guise could prompt outrage.

What has elicited this adverse reaction is that this festival and its sexually permissive ritual, has been attributed to one particular local farming community. The objection raised is against the implication that within this community taboo sexual behaviour has been a norm. The more rational elements opposed to this book ask for the historicity of this rite. Where is the research that such a practice was indeed rife? The grouse is that in the absence of proof the writer is merely propounding hearsay and myth as fact. The more irrational elements of course threatened bodily harm. Let it be noted, there has been no ban so far on the book though a case against it has been registered. Distressed by adverse reactions and threats, the author has retracted his works.

A parallel trajectory though on a much grander scale has been charted by the career of eminent writer Salman Rushdie. On October 5, 1988, following Khushwant Singh’s review "apprehending the reaction it may evoke among people" the administration took cognisance and invoked the laws against blasphemy in the Indian Constitution and slapped a ban on the import of Satanic Verses. The Indian government stance was vindicated by governments worldwide following suit.

Justice is blindfolded. It does not weigh literary merit against human lives quite the way us creative writers would want. It seeks to pre-empt violence and does not quite care whether a well written book or a crass fire-tongued political opportunist risks brewing ferment and violence. India’s citizenry is vastly complex and diverse. In this plural multicultural society, fracture lines and intricacies make up its rich history such that religious or communal slight often is incendiary. Since we do not yet inhabit a perfect world -- model, self regulatory, fair and balanced -- there is wisdom in legal mediation and constitutional processes.

Many contemporary critics echo Steve Oberski’s sentiment: "Book burning is one (rather extreme in my opinion) valid form of criticism." By extension protesting, asking for objectionable portions to be removed, seeking judicial interventions or even gently pointing out to publishers that their business interests could be quite severely hurt: are ultimately critique in this way past the post, post-modern literary experience. None of these reactions can be condoned. Neither can they be wished away despite the sanctity the written word is accorded.

The fact is that words have power. Like it or not with publishing clout, press and attendant privileges, the writer’s voice is not only audible but also resonant. What recourse then does the ordinary reader have when this voice deeply offends or interferes with his state of well being? The stance taken is that taking offence is an easily misused tool. Sadly in most cases it is. Or is inappropriately expressed via violence.

Some of art is dangerous. It lends itself easily to another form of warfare, sometimes deadlier. Case in point: quite subtly the Russian accented English of the Cold War era villains have been replaced by Arabic accents in Hollywood movies. No one needs to be told who the "universal" enemy is right now. Even the location of movies that have nothing to do with world politics, like James Bond, Mission Impossible or Transformer has come to be situated in the Middle East. Depending on which side of the fault lines the vantage point is, this phenomenon may be innocuous or corrosive. As artistes and writers it is our duty to be offended too, to point out how certain expressions are acts of violence in their own ways. And in speaking out, the power of offence can be dissipated.

While India watched horrified the grimness of the Charlie Hebdo killings, there was also the feeling of discomfort with how this was made to be a freedom of expression issue. Killing in any form and for whatever reason is of course the most reprehensible act condemned by all religions equally. Are there instances when art and artistic licence may go too far? In a world increasingly being taken over by absolutes, is there a need for moderate voices?

Yet art is required to shatter notions of comfort and resignation. While on the flip side any group of individuals is somehow free to proclaim offence and attempt to forever silence the uncomfortable voices. What complicates the matter is rarely are the artwork and its extreme critique on the same geographical or moral planes. Social issues rarely have an easy resolution. It is crucial to debate and disseminate a wider understanding. In a powerful vibrant democracy like India, this possibility of debate and dissent has been its greatest glory. Sometimes as in all debates, not all may be perfectly happy with how it ends. Yet as a mark of an open vibrant society our constitution, lawmakers and powers-that-be ensure all voices are heard.