Some curious monuments that are not the usual ‘must see’ items in travel guide books

For those intent on exploring the cultural heritage of Lahore, there are well-known sites like Lahore Fort, Badshahi Mosque, and the Shahdara Tombs, all easily accessible by a vehicle. However, I, along with a group of young cyclists, have been pedalling about for the past few months, and have unravelled some curious monuments that are, regrettably, not the usual ‘must see’ items in travel guide books.

While their location in narrow alleys and congested bazaars may be a reason for the inaccessibility, their dilapidated state may be a better explanation of why few are interested in sparing time to get there. Sunday being a regular workday for our cycling group of young professionals -- with this able, old hand alongside -- we started with the Begumpura area. The locale carries its name after Begum Jan, the mother of Nawab Zakariya Khan, a Governor of Punjab during the reign of the lesser Mughal Emperor Muhammad Shah.

Gateway to a pleasant garden

Heading west on GT Road, I watched the distance on the bike GPS computer roll up to 1.8-km from the preceding Shalimar Link Road intersection. As expected, this is where the striking two-storey Gulabi Bagh Gateway, profusely decorated with brilliant, floral-themed ‘Kashi-kari’ mosaic tiles, came into view on the right side. The gateway appears reasonably well-preserved, compared to many other monuments of that era.

The Gulabi Bagh was laid out in 1655 as a pleasure garden by Mirza Sultan Beg, a cousin of Emperor Shah Jahan’s Persian son-in-law Mirza Ghiyas-ud-din Beg; the latter helped Sultan Beg climb up the nobility ladder, to the rank of Mir-ul-Bahar in the puny Mughal Navy.

Fascinatingly, the words ‘Gulabi Bagh’ are said to be a chronogram whose hidden numerical value stands as 1066 (Hijri) -- or 1655 AD!

Besides the main entrance arch (peshtaaq), the façade has four smaller arches; of the latter, the two on the ground level are simply deep-set alcoves, while those on the upper storey are openings of balconies set with stone-carved jaali (net) guardrails.

This Timurid aiwan design of the gateway is common to many pleasure and funerary gardens of the Mughal era. The roof of the structure is, however, not topped with any minarets, kiosks or turrets, as is the case with most other Mughal garden gateways.

As we passed through the entrance arch, the chowkidar’s unkempt bedding and slippers, scattered shabbily in one of the two open side chambers, seemed to mock appallingly at the lyrical Persian stanza inscribed on the entrance:

A garden so pleasant, the poppy sullied itself with a stain of envy,

Thence appeared the flowers of Sun and Moon as lamps for adornment.

The Gulabi Bagh is no more extant in its original size and splendour. The present-day gardeners have, however, made a modest attempt at creating a garden with clipped hedging plants arranged in geometric patterns. With unsightly residential buildings encroaching on three sides, what is left of the garden is actually a narrow stretch leading up to the tomb of Dai Anga, about 100 metres ahead. If the tomb was constructed in the centre of a square garden, as was usual, the area of the original Gulabi Bagh works out to be about ten acres.

A Tomb amidst the garden

Walking up to the squat tomb of Dai Anga, we first went around it to check the commotion. To our surprise, children who were playing cricket just behind the tomb scurried away, and some women hastily shuffled indoors, adjusting their dopattas in the presence of strangers who they thought were trespassers on their property!

When Emperor Shah Jahan’s wet nurse, Dai Anga, died in 1671, she was entombed in Gulabi Bagh. Mirza Sultan Beg, whose pleasure garden was appropriated for funerary purposes, was most likely her son-in-law, for a second grave of a certain Sultan Begum lies adjacent to Dai Anga’s. This grave is wrongly attributed by some to Shah Jahan’s daughter, for he had none by that name. Mirza Sultan Beg, had not lived long to enjoy his garden, nor was he interred in it, when he died in 1657 in a firearm explosion during a hunting excursion at Hiran Minar, near Sheikhupura.

When viewed from afar, something appears odd about the tomb; it does not take long for a keen observer to note that the corner kiosks (chhatris) atop the roof are oversized. Or, perhaps, the Timurid low dome on a high drum, the Rajasthani chhatris, and the Persian cusped arches, are fusion of one style too many for subtlety. The walls of the tomb, now shorn of ‘richly decorated enamelled pottery’ (which the historian S M Latif noted in 1892) give a rather bland appearance. Remnants of a chevron patterned mosaic on the dome are visible; arabesque and floral-themed Kashi-kari mosaic tiles can also be seen to run along the top of the tomb.

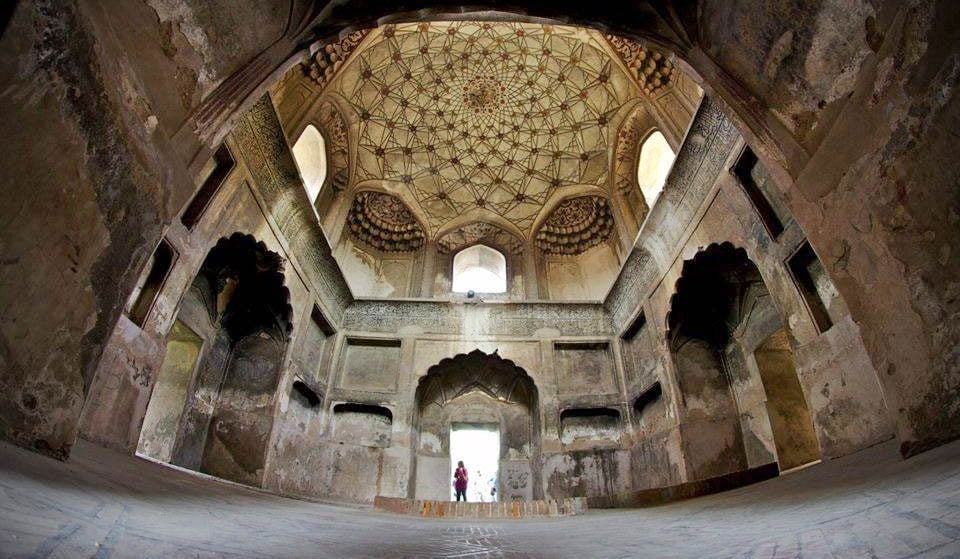

Entering the main chamber of the tomb, we were careful not to step on the low brick cenotaphs, which had been put up after the original marble ones were removed, purportedly by Sikh vandals. The actual graves are in an underground chamber, now sealed and inaccessible. The upper walls of main chamber are richly embellished with Quranic calligraphy, while the inside of the dome depicts an apt celestial theme. The main chamber is surrounded by eight interconnected smaller ones, based on a floor plan known as Hasht-Bihisht or Eight Paradises. How convenient, I thought, to have such a walk-in convenience for the Hereafter!

Suckling the infant Khurram (future Shah Jahan) certainly boosted Dai Anga’s family fortunes, for her husband Murad Khan, a magistrate in Bikaner, became a favoured courtier under Khurram’s father, Emperor Jahangir. Dai Anga’s name also lives on for her services to the public, as she built a mosque in Lahore’s Naulakha area in 1649, before she proceeded for Haj. It is a pity that someone who bequeathed Lahore with one of its most beautiful mosques, lies in an utterly neglected tomb.

Cypresses for eternity

Sarvwala Maqbara, always had an oddity about its name, so after doing the Gulabi Bagh, we pedalled on to find out more. Winding around some narrow streets, we soon got to the tomb, which is actually just 200 metres north on a crow’s flight from Dai Angatomb. Were it not for the decorative tiled panels with the cypress motif, one could mistake the square structure for an overhead water tank. The tall green cypresses, with an undergrowth of brilliant blue irises, make the tomb unique, for the cypress symbolism of eternity and agelessness so common in Persia, has rarely been expressed in the sub-continent’s funerary architecture.

Sharf-un-Nisa Begum, the occupant of the tomb, was the unmarried sister of Nawab Zakariya Khan, the Mughal Governor of Punjab. Given to piety and religious ritual, she used to recite the Quran each morning in this tower, climbing and descending by a ladder.

On her deathbed, the virtuous lady expressed her desire to be buried inside the tower, up and away from the inquisitive eyes of the passers-by. A Quran and a bejewelled sword are said to have been placed on the sarcophagus at the time of burial. All openings were bricked up and the upper walls covered with cypress-themed ceramic tile panels, four to a side.

Though much has been made of Sharf-un-Nisa having designed the tomb herself, it is more likely that it was already an elevated garden lookout of the Nawab family, and was improvised as a tomb on the lady’s desire. The tomb was built in the first half of the eighteenth century, though some sources are more definite about the year being 1745.

During the Sikh reign in Punjab, the tomb was pried open and ransacked to hunt for supposed hidden treasures. It was also stripped of bronze facing on the lower portion of the walls, leaving them with a battered, forlorn look.

Keen to peep inside from the single arch that remains open after the Sikh vandalism, we arranged for a ladder from one of the nearby houses. Since the ladder was not tall enough, and several ‘Spiderman’ attempts had failed, we thought we might have been spared an unwelcome reception by bats and creepy crawlies in a dusty cavern.

Hemmed in by houses, criss-crossed by overhead electric wires, and used as a cricket playground in its immediate surroundings, one wonders how long before Sharf-un-Nisa’s tomb cypresses wilt away, bringing her quest for eternity to a poignant end.

The article is the first in a three-part series on the hidden jewels of Lahore.