Romila Thapar on history and politics of India

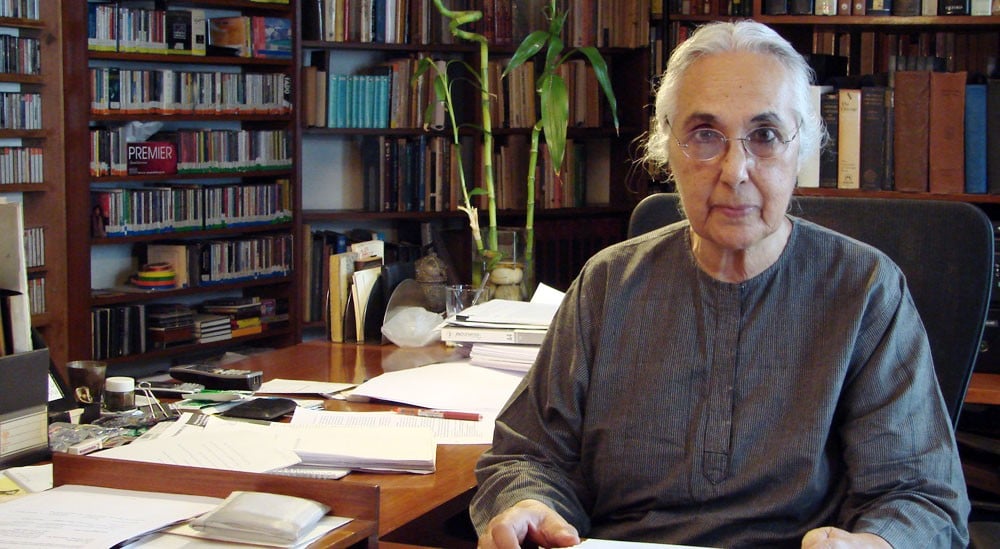

Professor Romila Thapar, 83, needs no introduction. She is known among intellectuals of the world for her path-breaking work on Indian ancient history. She has memories of old Lahore where her grandfather used to live at Lawrence Road. It was her father, a doctor in the Indian army, who made her go through old manuscripts, thus developing in her an interest for history.

More recently, Prof. Thapar has been in the news for her third Nikhil Chakravartty Memorial Lecture "To question or not to question: That is the question" where she said that and experts shied away from questioning the powers of the day" and that they must question more.

When she was young, her father offered her to choose between dowry or money for a degree from London University; she chose degree over dowry and did not look back. Although her writings don’t reflect feminism, she calls herself a feminist and pleads that history written by feminist historians should be taken seriously.

Thapar is among the founders of the Department of Modern History at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), known for ‘deconstructing’ myths. She has inspired generations of history students. Her book Somnatha: The Many Voices Of A History led to condemnation by Hindu bigots and groups of Non Resident Indians (NRIs), living in the US are said to have opposed her appointment at Smithsonian Institute, Washington.

She has refused India’s highest civilian award Padma Bhushan twice. In a letter to the Indian president, she wrote "I decided some years ago that I would only accept awards from academic institutions or those associated with my professional work, and not accept state awards."

Elegant and humble, Thapar is thoroughly committed to her scholarship, her memory exceptionally sharp for an octogenarian. Anti-communalist to the core, she spends her time reading and delivering lectures and so on;

At her beautiful house in Maharani Bagh, New Delhi, it is difficult to tell the sitting room apart from her study, both lined with endless collection of books.

Excerpts of an interview with her follow:

The News on Sunday: Why is secular India becoming a Hindu India?

Romila Thapar: This is a long story. It goes back to the period where we had a secular nationalism which was anti-colonial but we also had two, at that time lesser, movements: the Muslim League with its emphasis on Muslim religious nationalism and the Hindu Mahasabha with its emphasis on Hindu religious nationalism.

What has happened, in a sense, is that the Muslim religious nationalism was in its own turn successful in the creation of Pakistan. So those who were associated with Hindu religious nationalism wanted the same kind of political state to emerge in India. This did not happen because there were enough people in the national movement then who were committed to secularism and therefore it remained a secular state.

What has happened today is partly that there has been a kind of disillusionment with the way in which development has taken place in the last couple of decades, and therefore there is a turning away from the values that were upheld by the previous governments. There are now expectations from the possibilities of new values. It is interesting that the present government which had based its electoral campaign on issues of development, after coming to power, now seems to concede additional agendas. Attempts are being made to try and bring in a kind of ‘Hinduisation’ of state and society. This has started becoming more vocal.

I think in the process of neo-liberalism and market economy, there has been a marked growth of the middle class. But, at the same time, it has brought a highly competitive system in which there is a great insecurity. When there are periods of insecurity, people tend to turn to easy answers. The idea of giving primacy to Hindu citizens has an appeal for some of those looking for easy answers.

TNS: Don’t you think the combination of neo-liberalism, business and religion is lethal and anti-people?

RT: Yes, it is a lethal combination because neo-liberalism means leaving things to individual initiative whether it is investment or any other form of money-making. And the contradiction, of course, is that in order to create an ideologically-motivated Hindu state, you have to be very disciplined in observing the regulations of what is being projected as the requirements of such a state, which may contradict the economy. And I think that one of the possibilities that may happen in the time to come is a conflict that this contradiction may lead to.

TNS: Why did secular forces become weak in a country whose major claim was that it was a secular state?

RT: I think the people who were secular took it for granted that secularism had come to stay and they were too dependent on the idea that the state was secular and would ensure secularity. They did not do enough work amongst people to make them understand what a secular society actually means and the kind of laws it requires.

Here in India we have a different definition of secularism which I think is not adequate. We have regularly talked about secularism as the co-existence of all religions. Now that is not enough. You can have co existence of all religions but unless there is a social equality amongst all religions it is not secular, and social equality may be absent where there is only co-existence of religions. We have believed in co-existence but we have also allowed some religions to have a more dominant role. That is where our definition is inadequate.

TNS: Do you think there is some movement or there are people who are thinking along these lines?

RT: At the moment there are individuals who are thinking on these lines but there is no substantial movement as such, at least not that I know of.

TNS: That looks like a sad state of affairs because people in Pakistan, particularly secular people and liberal people look towards India?

RT: Yes, there seems to be a rise in what has begun to be called Hindu fundamentalism, which may be a contradiction in religious terms but not in political terms. There is certainly despair at this happening but, at the same time, one must remember that should it get really bad, there is bound to be a challenge. So let us hope that we can meet the challenge. And there are people opposed to it.

TNS: If I correctly recall you also said that the term Hindu was coined later on, it was first Brahman and ….?

RT: No, it was not Brahman. There was no single term to cover all the religious sects. The term Hindu was coined when those living in West Asia mentioned the Hindus as the people living across the Indus. Al-hind was linguistically connected to Sindhu/Hindu, in that sense. Initially it simply meant anybody who lived beside the Indus. It was a geographical term and then gradually, when there was a need to separate Hindus from Muslims and Christians and so on, it came to be applied to those who were not Muslims and not Christians. It began to be used by about the 14th or 15thcenturies in a religious sense but originally it is a geographical term.

TNS: You said that the Buddha was the first rationalist…?

RT: I did not say that he was the first rationalist. I said Buddha represented groups of people who challenged Vedic Brahmanism and they challenged the sanctity of the Vedas as divinely revealed. They challenged the concept of the soul and various other ideas. But Buddha was not the first rationalist nor was he the only rationalist; there were others.

TNS: Why did Buddhism fade in India and flourished in other parts of the world?

RT: It was extremely important at one stage. It was almost the dominant religion and then in competition with Brahmanism it declined. It was pushed to eastern India, from eastern India it had links with Tibet and then it went to South East Asia. Another branch went from Gandhara in north-western India to Central Asia and from there to China. So it became almost the dominant religion of Asia for a period, although it gradually declined in India.

TNS: While the Hindu right wing forces tried to strengthen their power, secular historians of the time contested their attempts. In the present context we do not have such kind of contest. You advised in your lecture to historians to question the Historical development. Do you think there is a need for mobilisation of historians?

RT: In my Nikhil Chakravartty lecture I argued that people should speak up where they disagree with actions relating to state and society. So I was bothered that not enough people seem to speak up these days.

I must point out that I have a problem with the word ‘mobilisation’ that you have used. It is not that we as historians were ‘mobilised’ during the last half century. We were secular historians and our reaction came out of the secular history that we were writing. You can’t mobilise historians; historians have to think of their own way of explaining history. Each historian has to be convinced that the kind of history he/she is writing is an explanation, or it provides an understanding of the historical problem being studied. As a historian I would find a secular history preferable to one that supports a purely religious perspective. But we as historians can’t go around ‘mobilising’ historians. They have to think of their answers themselves.

So if they are not asking themselves about the validity of the history they are writing, then what is one to do beyond critiquing it. This is because it is not history that is based on a critical assessment of the evidence, on a logical and rational analysis, on the use of all possible sources, and on other such considerations.

TNS: Textbooks are considered as a significant tool to transform knowledge. Textbook produced by you in the 1970s and 1980s aimed at inculcating a secular identity. What is your opinion on changing the textbooks by right wing forces?

RT: What we have to understand is that if the society is one in which there are multiple identities, each of these at some point is going to want its place in history. The historians, therefore, cannot say that we will include this but not that. It becomes a question of how the historian, who sees these multiple identities, represents them in an integrated way. In this connection we also have to re-examine the idea of identity. What do we mean by an identity? And we have to keep in mind that identities change when the historical context changes. Even if we are speaking of a single identity, we have to define it carefully as even single identities undergo change.

What do we mean for instance by Pakistani identity, Indian identity or Sri Lankan identity? What are these identities beyond the fact that they relate to nation-states? We have not really discussed them but have merely assumed them. The discussion would include the notion of culture, religion, language -- everything that goes towards the creation of communities and then of citizens. We need to look at them much more carefully in historical terms than we have, and from various perspectives.

Feminist history is absolutely essential because one cannot write social history without asking the kinds of questions that feminist historians are asking. One may agree or disagree with whatever their answers or generalisations are, but few would doubt the need to ask these questions. Similarly with Dalit history, questions have to be asked. What eventually emerges depends on how it is linked together with the rest of social history.

Discussions and debates can and do split historians into groups. Some historians were and are Marxists and some remain non-Marxists. There were extensive debates, as for example on the question of whether there was a feudal society in India similar to that of Europe, and if not then what were the ways in which it differed. These debates advanced our knowledge of what was called medieval Indian society. Those that see history from the Hindutva perspective are more concerned with pushing their ideology than with the historical debate.

If you are trying to understand a complex society, it has to be seen from multiple perspectives, each based on evidence and analysis. What the historian has to do is to test the reliability of the evidence used as well as the validity and logic of the statements that follow, and then see how best the understanding of the past emerges.

TNS: What are you writing now a day?

RT: I am not writing anything. I have finished with writing academic monographs!

TNS: How do you spend your time?

RT: I am reading, and delivering lectures and talks and so on, and doing smaller bits of writing, but not a book.

TNS: How do you see the future of secularism in India in the context of its current politics. Will it change?

RT: Oh, it is bound to change. I think there is going to be a lot of discussion, debate, possibly even confrontations, on the issue of defining secularism. But ultimately if we do survive as a democracy we have to be secular. There is no choice. It would [change] if we became a dictatorship. But then the politics of the whole region will change.

TNS: Do you see any signs of dictatorship in India?

RT: I don’t know. It is very hard to tell at this moment.

TNS: What about Delhi? Aam Adami Party (AAP) is a new phenomenon.

RT: I have only a little idea of how the electorate is thinking in the city. The AAP did once have much potential, but let’s see if that is still so.

TNS: Do you think relations between India and Pakistan will normalise?

RT: I sincerely hope so. Eventually that has to happen. When the entire area is culturally and historically so deeply intertwined, it will happen. I don’t see hostility going on indefinitely.