A Scotswoman who set up maternal and childcare centres in the many districts of the Frontier, from 1934-44, and lies buried in Nathia Gali almost unsung

India, the ‘Jewel in the Crown’, was glimpsed by British Memsahibs as a land of oppressive climate, cobras, cholera, cruel natives and death.

Every girl sailing east, even those vying to tie a knot with a handsome officer of the Raj, was always reminded of these perils by their aunts who had some experience of the tropics, or by their jealous rivals. However, the lure of British India, stories of tiger hunt, of nawabs and nabobs, an army of khidmetgars (servants) and the love of their husbands would entice them to cross the oceans. Some of them never returned ‘home’.

This then is a story of a Scotswoman, an ordinary memsahib with a conviction to improve the condition of the native veiled women of the Frontier province.

It all started last year when I visited the office of my friend Atta Muhammad Punwar, then Secretary Information in Sindh government, and started browsing a book. Punwar thought the setting of the book would interest me since I had been posted in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa as Secretary Excise. The book Thirty Years on the North-West Frontier -- Recollections of a Frontiersman was an autobiographical account of Leslie Mallam, one of the last chief secretaries of the colonial Frontier.

Leslie Mallam, the designated Deputy Commissioner of Kohat, was on a home leave to Oxford in 1934, when he met Marie Carruther, a family friend and charmed by her gaiety proposed to her. She accepted the proposal but was hesitant to go to India because of a premonition that she would never return home. The marriage took place the same year in July and the Principal of Lincoln College, Oxford was kind enough to lend his house to this wandering young couple for whom ‘home’ would thenceforth mean moving from one of the Raj’s palatial bungalows to another.

Marie Memsahib was thirty when she landed from the ship in Bombay in October 1934. The couple took the Frontier Mail (train) to Peshawar, called on the Governor and his wife and headed for the Cavagnari House, the Deputy Commissioner’s bungalow in Kohat.

After the initial settling days, she got into the typical memsahib mode -- organising the house keeping brigade of servants, arranging outdoor parties in the lawn for officers and their wives, riding with her husband to distant villages, spending hot weekends in the cool heights of Fort Lockhart, and picnicking on the banks of Indus near Kushalgarh with shotguns, fishing rods and picnicking baskets. Marie once caught a twelve-pound Mahseer. What else was expected of a deputy commissioner’s wife in the mid-1930s in a place like Kohat on the North Western Frontier!

However, the details of her activities in India show that Marie was bitten by the vision of ‘Empire with a human face’. In this she was ably supported by her husband.

Her contact with Flora Davidson, the lone lady missionary in Kohat, was instrumental in drawing her attention towards the plight and heart-rending sufferings of local women. In her first visit to Lady Griffiths Zenna Hospital, she came to know that all the nurses in the wards "were convicts and murderesses from jail". She wrote a strong-worded letter to the Inspector General of Civil Hospitals in Peshawar and got them replaced by a trained staff. Her letter was however taken as a serious challenge to the established order.

Her next focus was the welfare of Maternity and Child Health (MCH) and this is where she crossed swords with higher authorities believing in status-quo.

Midwifery in subcontinent was plagued by superstitious customs and unhygienic practices, and was a hereditary occupation without the benefit of modern training. This led to high infant and maternal mortality rates.

The MCH was dealt with by the Red Cross Society, a voluntary organisation administered by a council chaired by Lady Griffith, wife of the Governor. But the Red Cross Society was guided by the advice of Public Health Department through the inspector general (IG) Health. Marie, a member of the council from Kohat, locked horns with the Public Health Department over the centralised training of the traditional dais (midwives) in Peshawar. Marie opined that strict purdah system would prevent the local dais from the remote areas to travel to Peshawar to attend these trainings and therefore favoured local centres at district level.

However, after many stormy sessions in Peshawar, she was accused by the IG Health of undermining his authority and lacking experience of India. Undeterred, Marie opened a local women welfare centre in a rented building. This centre soon became a success story as more and more dais from neighbouring tribal areas turned up for trainings.

Sir Ralph Griffith, the Governor, was forced to acknowledge her growing reputation by presenting her Rs2000 to build a new welfare centre. Soon more people donated for a just cause and a vacant plot "just outside the city wall" belonging to the Jail Department was identified for this purpose.

However, there was one oriental twist to the tale. The prison and the hospital came under the same Inspector General and the plan to build a new women centre was thwarted for sometime -- but not for long. At the end of the year, a tragic news reached Kohat that the IG Health had succumbed to injuries after a bad fall from his horse while hunting near Peshawar. His successor backed Marie and so Mallam Welfare Centre was completed. It was opened by Lady Cunningham, the new Governor’s wife.

In a short time, similar centres were opened in many towns by their respective municipal committees. As planned by Marie, a large provincial Maternity and Child Welfare centre was established in Peshawar but after her death in 1944.

In 1938, Mallam took his first home leave and left for England via Levant visiting Jerusalem, Nazareth, Damascus and other holy places. It was during this journey that Marie’s health deteriorated and, by the time the young couple reached Athens, she had lost considerable weight. Back at home, they received the shock that Marie had insulin dependent diabetes and the stock of daily injections of insulin had to be shipped from England as this drug was not available in India. On medical advice, the couple also decided to adopt two children, a boy David and a girl Judith.

Back in the Frontier, Mallam’s request for transfer in view of Marie’s illness was granted and he was placed as District Judge, Peshawar for some months before moving on as Political Agent (PA), Malakand, Dir Swat and Chitral. Marie and the two children use to accompany the PA on tours in the remote villages. Marie continued her work for the betterment of mother and child health.

Mallam was posted as Chief Secretary (CS), Peshawar from 1941 to 1944. He fondly recorded in his memoirs that one great advantage of being the CS was that every year the secretariat moved to Nathia Gali, the summer headquarters of the Frontier Province.

It was his last year as CS when the tragedy struck the family. Marie was pregnant and India was not geared up medically in those days to deal with diabetes. She continued with her usual chores, which included looking after the Red Cross, and Maternity and Child Welfare Centres. On March 25, 1944 she gave birth to a boy (Marcus) in Lady Reading Hospital, Pehawar but could not recover from the caesarian section. She was shifted to Nathia Gali where she died on June 4, 1944.

Marie’s coffin, draped with a Red Cross flag, was carried by a band of Gurkha troops with full honours to the cemetery. "She was only forty years old".

The Indian Red Cross Society placed a memorial brass plate at St John’s Church, Peshawar Cantonment with the following inscription:

IN LOVING MEMORY OF

CONSTANCE MARIE MALLAM

KAISIR-I-HIND MEDAL (SILVER)

WIFE OF LT. COLONEL G.L.MALLAM CIE.IPS

A quick trip to Kohat was arranged by my friend Shahzad Bangash. Not much had changed at the Cavagnari House in Kohat cantonment, except for the occupants. It is now the official residence of the Commissioner instead of the DC. The flower beds were exuding splashes of colour and fragrance, hedges were well-trimmed, lawns mowed and the house well-kept.

The Cavagnari House was "silver gleamed and glass sparked" in 1935 when Mallem and Marie received their royal guests, Princess Alice and the Duke of Athlone. The Princess’ recorded remarks explain her astonishment: "I had been brought through some of the wildest country I had ever seen and I expected an outpost of Empire and an earth closet. This is like a palace". She later helped the couple in adoption of their two children. Princess Alice was the longest living granddaughter of Queen Victoria who died in 1981.

Contrary to Cavagnari House, we found Mallam Welfare Centre in a dilapidated condition. The building was rebuilt after it was damaged in an air raid in 1965 war but it was past its heydays. It is still run by district Red Crescent Society which also includes a vocational training centre.

The few trainees and the staff of this vocational centre that we met on that day fondly remember Samar Minallah, the DC’s wife who was posted here in 2000-1, who took keen interest in the affairs of Mallam centre and the place was briefly rejuvenated to its glory days. But unlike Marie, she being the wife of a Pakistani civil servant, was never rewarded for her social services.

Riaz Mehsud, the new DC of Kohat who accompanied us to Mallam centre promised to look after this place and to thwart the sinister move by local politicians to convert this place into a school and occupy the shops. All along the front wall were 25 shops which were rented out to political favourites for the accrued monthly sum of Rs 19,668 only. The lone LHV at the Mallam Centre had left the job many months ago due to meagre salary. The furniture was mostly broken and dusted. Missing from the wall of the main office was Marie’s portrait, allegedly taken away by the last LHV in lieu of her salary.

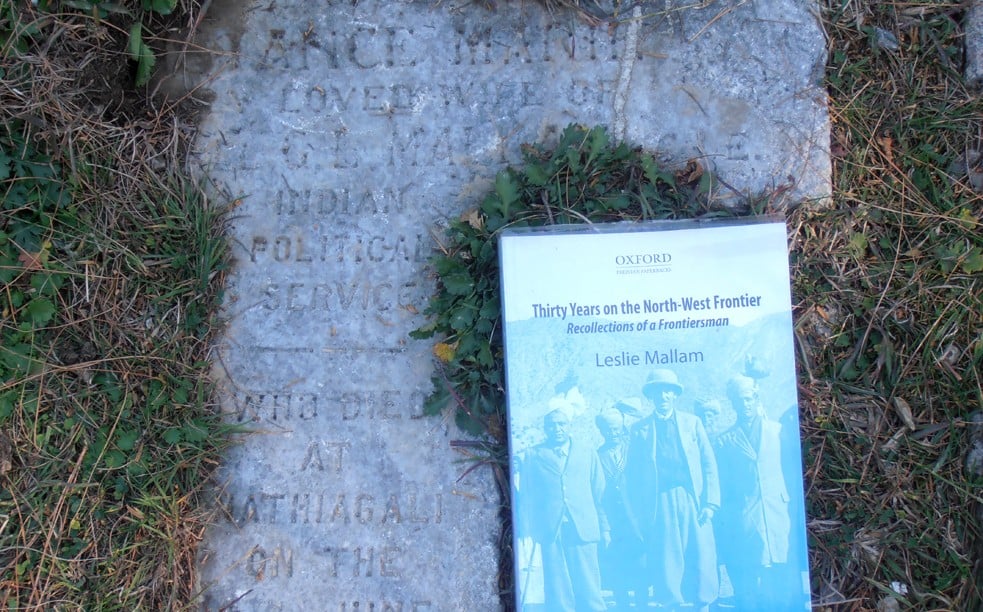

In quest for Marie’s final abode, I next headed for Nathia Gali. It was late afternoon and I was frantically cleaning the wild undergrowth over a tombstone in an ill-kept Christian cemetery of Kalabagh near Nathia Gali. "Good evening Sir", the commanding voice of an approaching old man greeted me as if I were a Christian looking for the final resting place of a long dear departed. On all fours, I politely returned my greetings. Short of desecrating a grave, it was difficult to explain to a simple aged villager of what I was up to in a forsaken cemetery.

Lubna Khan, my civil service batchmate who that morning decided to accompany me on this little trek, smiled at my predicament. Marie’s missionary grandmother had gone to India and had died there. This Marie thought would be her fate too. Her premonition in 1934 about her death in India was as true as the foreboding of the three witches in Macbeth.

Ten years later, she would lay buried eight thousand feet up in the foothills of Himalayas, far away from her beloved Scotland and among people who have forgotten her good work. Eighty years after her death, we were perhaps the only ones who came looking for the grave of this extraordinary Scotswoman who dedicated her life for the well-being of the native women.