A peek into history to know how the British government and the American administration prevented the emergence of several states in South Asia except Pakistan and India after Partition

The June 3, 1947 plan mandated the creation of two new dominions--India and Pakistan--on August 15, 1947 out of British India. It, however, did not stipulate what the hundreds of Indian princely states were to do. All the British government had announced was that from August 15, 1947 all treaties and agreements between the princely states and the Government of India or the British Government would come to an end.

With this Lapse of Paramountcy, all rights and obligations which the princes of India had surrendered to the British Government reverted to them. Hence in the words of the Cabinet Mission’s Memorandum on the Princes, with the Lapse of Paramountcy, the princely states would become ‘wholly independent.’

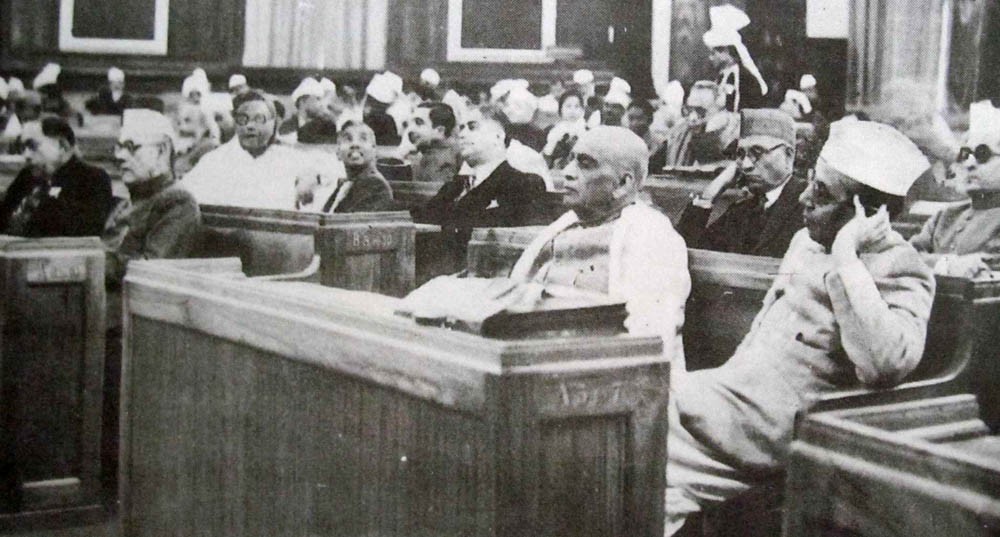

While the All India Muslim League did not think too much about the implications of the Lapse of Paramountcy, the Indian National Congress knew what the independence of the princely states meant, and tried its best to ensure that all princely states accede to the new Indian Dominion before the Lapse date. Where the maneuverings of the Congress, the tough stance of Sardar Vallebbhai Patel, the Minister for States and V.P. Menon, Secretary of the States Ministry is very well known, the effort put in by the British Government and the American administration to prevent the emergence of any further states in South Asia except Pakistan and India is little known. For a number of princely states, their hopes for an independent existence were thwarted by such attempts and therefore their role in the emerging future of South Asia was critical.

With the approach of August 15, 1947, the British government was of the opinion that even though the states were technically independent from August 15, 1947, they should still align themselves, in one way or another, with the successor dominions. A telegram from the Commonwealth Relations Office to the dominions stated:

"United Kingdom Government believe that future of Indian States inevitably lies in association with British India with whose territories their own are inextricably intertwined…They therefore hope that all Indian states will enter into a federal relationship with one or other of the new dominions of India and Pakistan or, failing this, enter into particular political arrangements with them and thus retain their connection with the Commonwealth. Some time may elapse before all of this and some, particularly Hyderabad, have so far declared their intention not to federate with either Dominion. Thus there is likely to be a period during which international status of at least some of the Indian states will be undetermined. In practice we expect that diplomatic representatives of India or (when they are appointed) of Pakistan, will continue to look after the interests of the Indian states even in advance of the time when by accession to one or other dominion they merge themselves for international purposes with that dominion."

The attitude of the British government towards entering into any kind of a relationship with a princely state which had remained aloof was deliberately kept vague, in the words of the Secretary of State for India, so that they were not charged with ‘disintegrating India’ especially if such an action would lead the Congress to ‘withdraw its application for Dominion status.’

An article in the Hindustan Times clearly elucidated the antagonism of the Congress towards any princely states maintaining separate relations with the British government. It read: "It must be clearly understood, however, that the Indian Union will consider it a hostile act if there is any attempt by Britain to conclude any treaty or alliance involving military or political clauses. As for the Indian states, they cannot be permitted to have any foreign policy or contact apart from the Union. It is inconceivable that the Union will seek British assistance after June 1948 in its relations with those parts of India which stand aloof from it."

Nehru’s clear statement to Reuters on foreign countries recognising princely states as independent also served as a major obstacle for the princely states, since foreign states preferred good relations with the future Dominion of India to recognition of states which might not survive for a long time. Nehru had noted: "We will not recognise the independence of any state in India. Further, any recognition of such independence by any foreign power will be considered an unfriendly act."

However, some princely states had already been in touch with various governments, especially those of America and France, on the question of recognition of independence after August 15, 1947. The American government was particularly alarmed by reports that several Indian princely states wanted to remain independent and was in constant touch with the British Foreign Office on the issue. The American government agreed with the British government’s opinion that they should not recognise any princely states as independent on August 15, 1947 and should wait and see which states remained independent before announcing a policy on how to regulate relations with them. The Secretary of State, Lord Listowel, explained to Lord Mountbatten in a letter:

"A member of my staff has been shown confidentially by a member of the American Embassy the instructions issued by the State Department to the US Ambassador at Delhi about the attitude that he and American officials should observe towards the Indian states. The State Department have indicated that they do not wish any formal dealings to occur between American representatives and the governments of Indian states while the negotiations for the inclusion of the states in one or other of the two dominions are continuing. They recognise that at some later time it may be necessary for the US Government to determine its attitude towards any states which remain outside the two dominions but they attach importance to their remaining uncommitted so long as there is any prospect of the states who have asserted claims to independence entering into political arrangements with one or other dominion. This is very satisfactory."

The American State Department was also active in preventing other states from recognising the independence of the Indian princely states. A note sent to the India Office clearly showed the role American diplomats played in preventing certain Arab states, which had ties to a number of Muslim princely states, from recognising the independence of some states. It read:

"Mr Lewis Jones of the American Embassy had been good enough to show me an instruction from the State Department to its posts in the Middle East from Cairo to Delhi stating that information has reached them that certain Arab States may be contemplating diplomatic recognition after 15th August of certain Indian states as separate international entities, and requiring them to make it known to the governments to which they are accredited that the US share the desire of HMG [His Majesty’s Government] in the UK that the Indian states should become associated with one or other of the two new dominions and have no intention of according to any Indian state separate recognition."

Thus, even before the Lapse of Paramountcy, it was assured that no foreign power would recognise any of the princely states as independent entities. The aim of this policy, spearheaded by the British and American foreign departments, was to ensure that the Indian states saw no option but to accede to either dominion after the Lapse of Paramountcy and were not encouraged to stay aloof by the tacit support of any foreign power. This attitude ensured that hundreds of princely states signed on the dotted line before August 15, 1947 and within a few years were extinguished.

More on this topic can be found in my forthcoming book: A Princely Affair: The Accession and Integration of the Princely States of Pakistan, 1947--55.