Lessons to learn from Raza Rabbani’s tears and sense of shame for supporting a vote which the party discipline and not his conscience had dictated

The 21st constitutional amendment has come like a new year’s gift from the parliament. Its unanimous passage heralds a parallel military justice system for a period of two years, with the express purpose of eliminating the recently rediscovered menace of terrorism in the country once and for all.

In the run up to the passage of the bill, murmurs of principled objection to the concept of military justice were faintly audible. However, with all heads of the political parties whipped into a 9/11-like patriotic line by the uniformed political overseers, these faints echoes of dissent and conscience quickly disappeared. The opposition to the Act was also made to be seen to be indefensible in the face of patriotic fervour and mobilisation of the public consensus on the narrative of judicial failure by all sections of the media.

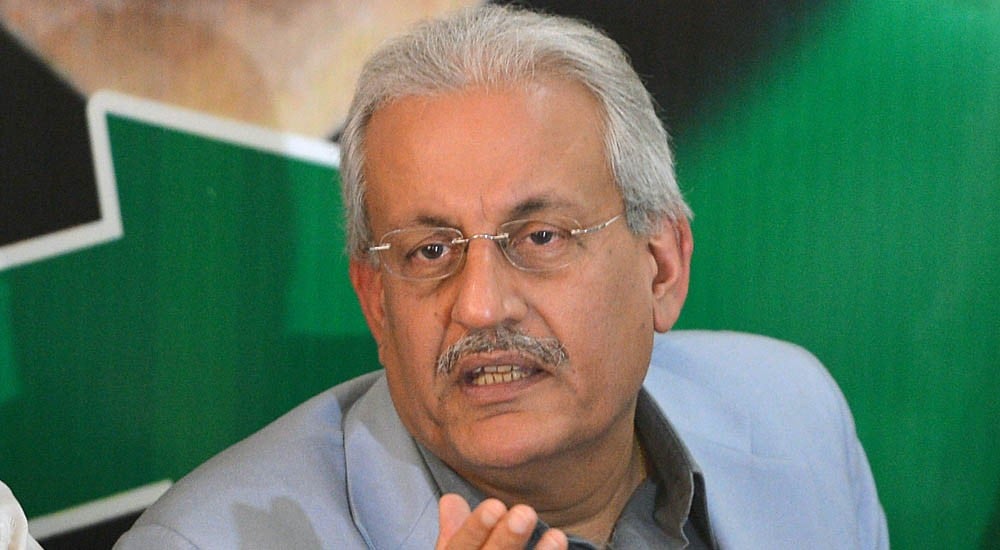

Yet one lone voice of constitutional probity and conscience rang out loud in the form of a short teary-eyed speech in the Senate of Pakistan. And the voice was that of none other than Senator Raza Rabbani, the architect of the 18th Amendment. This was his finest hour which lasted barely a few minutes.

His speech, though short on eloquence and heavy on emotions, reminded me of the resignation speech of the British Labour party cabinet minister, Robin Cook, on parliamentary vote on the British government’s decision to go to war with Iraq in 2003. On the day of the vote, Robin Cook, a stalwart of the Labour-left, resigned his cabinet position to join the ranks of anti-war dissident MPs and made an impassioned and eloquent speech which torn to shreds the painstakingly-built case for waging war on Iraq. His was the finest resignation speech from a Labour politician in recent history which won standing ovation -- a departure from parliamentary traditions -- from both sides of the house.

Raza Rabbani made his "Robin Cook speech" -- though sans resignation -- a day earlier than the vote, when he chastised the parliament for even entertaining the unconstitutional notion of military courts. He termed the parliamentary endorsement of the military courts as the last breath of its constitutional soul. On the day of the voting in the Senate, he offered his tears and sense of shame for supporting a vote which the party discipline and not his conscience had dictated.

Though he was derided by vast sections of the media, Rabbani was tracing his dissent to an established parliamentary practice which straddles the intertwined issues of party discipline, free vote and the conscience vote. This undoubtedly defined another ‘new’ in the Pakistani parliamentary history. It was only Rabbani’s short speech which focused on these issues while the rest of the parliamentary lot was meekly submitting to the party discipline. His performance highlighted two important issues of conscience vote and party whip. Though he did not defy the party line, he nonetheless made it known that he was doing it with a very heavy heart and under the unbearable heaviness of his conscience.

In Western democracies, the practice of free vote is an established matter. A party leader usually allows a free vote when he or she feels that the issues under discussion have placed the parliamentarians between the rock of personal conscience and values and the hard place of party discipline. For example, in recent years, political parties in the Western democracies have allowed free votes on bills ranging from capital punishment to abortions.

When this option is not made available to the parliamentarians, on issues that evoke strong values, this often leads to parliamentary rebellion against the party line. The most notable case in point is the largest parliamentary rebellion with the Labour party over the British Labour leader Tony Blair’s decision to wage war on Iraq with parliamentary authorisation.

Here in the debate over military courts, even a flicker of rebellion was not seen. Yet the lone man standing up for conscience vote was a breath of fresh air. While it is possible to argue that the Pakistani parliament needs a robust party whip system to prevent the monetarily-lured defections which have done irreparable damage to the process of the party political development and democratic consolidation, Rabbani’s emotional plea for conscience vote should be taken seriously.

Our history is riddled with the making and unmaking of governments through engineered floor crossing and party defection, as was the case in the 1950s and 1980s. This led to the weakening of both party and parliamentary systems. Against this sad backdrop, while the law on floor crossing is contextually justified, it also has the unintended effect of narrowing room for voicing dissenting views within the political parties.

Rabbani’s speech has brought into sharp focus the undemocratic function of the political parties themselves. Strangely, the JI and the PTI are the most democratically run parties in the country. Both the PML-N and the PPP are family fiefdoms. While the PPP in its original incarnation was more democratic in terms of its traditions of workers’ conventions, it has stepped back into the fortified four walls of the Zardari house. No wonder that after Rabbani’s speech, criticism with the party was voiced over not allowing discussion within the party on the highly controversial issue of military courts.

Even here, the PPP fared slightly better than the PML-N (with other dissenting voices of Aitzaz Ahsan and Bilawal Bhutto Zardari being clearly heard) where the long-winded speech of the interior minister dulled any residual critical faculties of the parliamentarians belonging to the party. In this grim parliamentary conformism, the voice of Rabbani for allowing conscience vote deserves a serious hearing beyond the din of patriotism. This is vital for the strength and growth of the parliament.

At a time when the parliament is assuming a new role as the custodian of democracy, as evidenced in its determined pushback to the PTI-PAT run on the parliament, Rabbani’s reluctant pro-military courts vote is yet another reminder of the importance of parliament as a bastion of constitutional probity.